Bob Dylan, 1964

Bob Dylan, 1964

Photo: © Daniel Kramer.

In August, a Bob Dylan album may well arrive in stores concrete and virtual. It may be called Shadows in the Night. It may have a song called “Full Moon & Empty Arms” on it; a stream of the tune was released without comment on his website a couple of months ago. Why Dylan chose to record a cover of an old Sinatra track isn’t clear; it may, or may not, be a clue that the purported album will consist of covers. Dylan has just finished shows in Japan, Eastern Europe, and Scandinavia; will head next to Australia and New Zealand; and may or may not be preparing for a swing through the U.S. in the fall.

We think of Dylan in a pantheon of great rock stars, at or near the top of a select list that includes the Stones, Springsteen, maybe U2, but not too many other active artists. But he behaves much differently. He’s released more albums than Bruce Springsteen in the past 25 years and played more shows than Springsteen, the Stones, and U2 combined. Yet he hardly ever does interviews and does virtually nothing to publicize his albums or tours. For someone who seems to be in such plain sight, he remains hidden, present but opaque, an open book written in cipher. Normal questions don’t seem to do him justice. You want to ask: What is Bob Dylan? Why is Bob Dylan? After listening to him since I was a kid and seeing him live for—gulp—nearly 40 years, I think I’m beginning to figure it out.

You have to start by disregarding the well-told narrative: The soi-disant vagabond’s rise through folk music to a place of utter domination at the highest level of literate, passionate, and difficult pop and rock music, all by 1966; a retreat and Gethsemane until 1974, when he came back, roaring and vengeful, more passionately focused than before, adding a remarkable personal dimension to his ’60s work. After that, depending on how generously you view his career, there has been either a long decline or decades of remarkable and kaleidoscopic creativity, culminating in the triumphs, late in life, of his five most recent albums.

For an artist as rooted in our musical culture as Dylan, the linearity of a narrative works more to disconnect him from the influences and traditions his work comprises than to explain him. First, you have to appreciate the many layers that make up his peculiar but unmistakable aesthetic. His work is grounded in acoustic folk-blues—ballads, chants, and love stories, populated with mystical or just plain weird meanings and themes, rattling and farting around like tetched uncles in the attic of our American psyche. To this add the dread-filled dreamscapes—unexplainable, unnerving—of French Surrealism, and then, arrestingly, the punchy patois of the Beats, who originally intuited the substratum of social stresses that would whipcrack across the ’60s and into the ’70s. Then factor in personal songwriting, a strain of pop he basically invented, doled out first with obfuscations, payback, tall tales, and lies—some by design, some on general principle, some just to be an asshole—and then the signs, here and there (and then everywhere, the more you look), of autobiographical happenstance and deeply felt emotion.

And remember that some of his narratives are fractured. Time and focus shift; first person can become third; sometimes more than one story seems to be being told at the same time (“Tangled Up in Blue” and “All Along the Watchtower” are two good examples). And then there’s plain sonic impact: Even his earliest important songs have a cerebral and reverberating authority in the recording, his voice sometimes filling the speakers, his primitive but blistering guitar work adding confrontation, ease, humor, anger, and contrariness, presenting all but the most unwilling listeners with moment after moment of incandescence.

And, finally, a key component often overlooked: Dylan’s artistic process. On a fundamental level, he doesn’t trust mediation or planning. The story of his recording career is littered with tales of indecisive and failed sessions and haphazard successful ones, in both cases leaving frustrated producers and session people in their wake. You could say the approach served him well during his early years of inspiration and has hobbled him in his later decades of lesser work. Dylan doesn’t care. During the recording of Blood on the Tracks,which may be the best rock album ever made, one of the musicians present heard the singer being told how to do something correctly in the studio. Dylan’s reply: “Y’know, if I’d listened to everybody who told me how to do stuff, I mightbe somewhere by now.”

He came to New York in early 1961, telling anyone who’d listen he’d ridden the rails, played with Buddy Holly, all sorts of nonsense. In reality, he was a fairly middle-class kid who’d hitchhiked, in winter, from the far north of Minnesota; in a way, this single act of propulsion toward reinvention by a 19-year-old is braver and more interesting than all his later tall tales of travel. He arrived in New York on the coldest day the city had seen in many years.

He was a prodigy, with a natural affinity for a medium that would, unexpectedly, afford a few people like him international acclaim and a permanent place in the cultural firmament, and lots of money too. His uncanny musicianship—producing enduring melodies and lovely harmonica solos—included an ability to effortlessly transpose keys that would impress professionals throughout his career. He also had a first-class mind, quick (almost too quick) of wit and relaxed enough to let inspiration flow without forcing it, yet also wiry, retaining permanently the complex wording of many hundreds of tunes. He soaked up the songs and the lore of folk and blues, cobbling together a shtick—an Okie patois, a shambling affect, and a fixation with Woody Guthrie, the socialist troubadour of the ’30s and ’40s and the author of “This Land Is Your Land,” who at the time was dying in a New Jersey hospital. It all served to disguise, at first, a mysterious charisma—with eyes, as Joan Baez remembered them later, “bluer than robin’s eggs”—and an apparent ambition that left a few damaged friendships, and egos, in its wake.

Baez, stentorian and humorless, recorded her first album in 1960 and was a star the next year. (She moved to Carmel and bought a Jaguar.) Dylan got an early rave in the New York Times, which led to his record contract. His second album contained several tracks that became standards. One, “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” was a strikingly imagistic portrait of a child returning from a journey to impart wisdom to an older generation. It’s the place where Dylan’s self-definition begins to merge with his songs. On his third and fourth albums, Dylan showed he was capable of increasing nuance. “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” the compellingly told true story of a barmaid carelessly killed by a moneyed young drunk, still able to make one’s blood boil, never mentions Carroll’s race.

At the same time, his mash-up of influences was creating deeper, subtler work, producing mysterious moments like the end of “Boots of Spanish Leather.” The song, spare and lulling, is a dialogue between the singer and his lover, who’s going on a journey. The woman wants to bring the guy back a present; the guy keeps saying he wants nothing besides her return. She finally says she won’t be coming back for a while—at which point the guy asks for a gift: some “Spanish boots of Spanish leather.” It’s not clear why the word Spanish is repeated. Maybe the guy’s heart was broken, or maybe the woman was right—he did just want something from her. But there’s a self-referential meaning to the song as well: Dylan’s own journey. Stars, after all, promise devotion to their fans and then disappear, leaving a simulacrum of their former selves that fans can never get something authentic from.

Beginning in 1965, in a 14-month rush, Dylan released three albums—Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, and Blonde on Blonde—each with two or three (very) major songs, three or four relatively minor (but still mind-blowing) efforts, and some doggerel and fun for leavening, all in a great spew of poetic verbiage. Dylan’s voice had deepened and matured; it rang with clarity, snickered with derision, led us compellingly, at its best hypnotically, through nightmares and fever dreams. “Subterranean Homesick Blues” introduced a modern, rock-and-roll Dylan, blasting off political aphorisms softened with absurdities—“Don’t follow leaders / Watch the parking meters.” Lacerating new epics made his old epics seem trite. Take “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)”; the title, and a potent Cold War reference in the first line, fixes our narrator seemingly as a wounded soldier, who then spends the rest of a very long song reflecting on the society he’s dying for. “Like a Rolling Stone” captured the second half of the decade in advance, a Scud missile of mockery directed at an entire pampered generation adrift. When Dylan howled the words “no direction home,” it was hard to tell if his tone was exultant or pained; it was a conundrum he and his audience have gnawed at ever since. In a telling example of how Dylan’s words can leapfrog meanings across decades, the song’s final silky lines—“You’re invisible now / You’ve got no secrets to conceal”—capture precisely the predicament of a new generation paradoxically rendered faceless by electronic connectivity and yet entirely without privacy.

Bob Dylan in Bratislava, Slovakia, 2010.

Bob Dylan in Bratislava, Slovakia, 2010.

Dylan’s remarkable work from this period is sometimes trivialized by stories about how he freaked everyone out by “going electric.” In I’m Not There, his cubistic cinematic portrait of Dylan, Todd Haynes represents the moment with the singer and his band mowing the crowd down with machine guns. Please. There were some boos at the Newport Folk Festival when Dylan and his electric band played there. But at least some of the reaction came from the high volume and poor sound quality of the performance, which was, after all, at a folk festival. Meanwhile, “Subterranean Homesick Blues” was Dylan’s first Top 40 hit, and “Like a Rolling Stone,” an unprecedented six minutes long, went to No. 2. Dylan’s move to electric is of course a key moment in his musical growth, and an interesting footnote in the history of 1960s American folk; but it was not a thumb in the eye of propriety. Everyone liked it!

Dylan is intensely private. More than almost any star I can think of, our understanding of his personal life is occluded and disjointed. His first wife was Sara Dylan, née Sara Lownds, née Shirley Noznisky. When they met, she was married to a guy in publishing in New York; early in their relationship, Dylan mentioned to an interviewer that he’d met a woman named Sara and that she was one of only two truly “holy people” he had ever met. (The other was Allen Ginsberg, though Ginsberg had never done a stint as a Playboy bunny.) “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” is widely seen as a tribute to Sara; it has a title that suggests the name Lownds and other lyrical hints (“Your magazine husband / Who one day just had to go”) and is placed ostentatiously to fill up the entire final side of Blonde on Blonde. Dylan’s memoir, Chronicles: Volume 1, some of which may be true, is at its most dyspeptic when the singer describes the hordes of hippies impinging on his and his family’s life by the mid-’60s. Using a motorcycle accident as an excuse, Dylan retreated in 1966 and began releasing country-flavored albums at long intervals to dampen his celebrity. In the meantime, he and Sara raised an eventual family of five in peace. The names and number of his children were widely misunderstood until the publication ofDown the Highway, a powerful, definitive biography by Howard Sounes, in 2001. (The children are Maria, from Sara’s first marriage; Jakob, whom you know from the Wallflowers; Jesse, a Hollywood and new-media guy, director of Will.i.am’s “Yes We Can” Obama music video; Anna, an artist who stays out of sight; and Samuel, a photographer who keeps a low profile as well. This is not to mention his second, secret wife and at least one other acknowledged child, but that’s a tale for another time.)

Dylan emerged in the mid-’70s to tour with the Band, release two of his strongest albums (Blood on the Tracks and Desire), and embark on a nutty and hilarious gypsy-caravan tour dubbed the Rolling Thunder Revue. His relationship with Sara was strained at this point, though she came along on the tour and even starred in his bizarre four-hour movie, Renaldo & Clara. But in the end, Dylan’s womanizing fueled what became a bitter divorce. His most plainly personal album is Blood on the Tracks, a lancing portrait of a romantic death spiral. (Jakob has said he gets no pleasure from listening to it: “When I’m listening to Blood on the Tracks, that’s about my parents.”) Among (many) other things, Blood on the Tracks is an exercise in emotional intensity, from self-pity and anger to ruefulness. There are obvious references to his wife in the wrenching “Idiot Wind” and also at the beginning of “Tangled Up in Blue” (“She was married when we first met / Soon to be divorced”). Blood on the Trackswas recorded in bizarre circumstances, first in New York and then more than half of it rerecorded in Minneapolis with a pickup band; yet its shuddering atmospherics and controlled, specific writing combined to make it the most organic and emotionally fulfilling work in Dylan’s canon.

The Rolling Thunder Revue saw the return of the lovely Baez; she sang “Diamonds & Rust,” her greatest song, a poison-pen love letter to Dylan, and did the frug behind Roger McGuinn during “Eight Miles High.” A decade on, in the ’80s, she and Dylan toured again, this time in Japan, with what was supposed to have been shared star billing. Baez inevitably became an opening act and eventually told the tour to fuck off, as she later told the story. Granted an exit audience with Dylan, she found him an aged version of the immature ragamuffin. He was tired but slipped his hand up her skirt for old times’ sake.

The next two decades were tough for him artistically; as Greil Marcus has put it, Dylan was essentially committing a “public disappearance.” Beginning in 1979, he tested his audience’s expectations and goodwill more tellingly than any punk by releasing three albums of unimaginative Christian-themed songs, along with two tours in which he plowed stolidly through this material. The problem was not Dylan’s beliefs, though they leaned to the crackpot; lots of acts had religious leanings—Van Morrison among them. It was how Dylan articulated those beliefs. To listen to the albums today is to enter a (not very) fun house of mediocrity and intolerance.

Dylan began to produce his own albums. He wasn’t dogmatic about it; he would once in a while bring in an outside producer—Mark Knopfler helped on Infidels, and Daniel Lanois superimposed a decent setting (and demanded a suite of coherent songs) for Oh Mercy. Other albums from the ’80s and ’90s were weirdly inconsistent in the quality of both the songs and the production values. Even weirder is the fact that Dylan was actually writing and recording some of his best work during this time. “The Groom’s Still Waiting at the Altar, “Blind Willie McTell,” “Caribbean Wind,” “Foot of Pride,” “Series of Dreams” … Authoritative and undeniable, they were better than anything his contemporaries were then releasing. Unfortunately, they were also better than anything Dylan was releasing and only turned up later on compilations albums.

In 1997, Lanois returned for Time Out of Mind. The critics went nuts over this work and the four regular releases since. I think these albums are woefully overrated, but they have sold well, and with the critics behind them, too, I’m willing to acknowledge the disconnect may be mine. But deep down I know that it’s hard to find, over the past ten or 15 years, more than three or four songs you’d stick on a mix tape to try to convince someone of this singer-songwriter’s greatness. Too many of his recent songs start with a pleasant-enough (or, more often, serviceable) riff—which is then beaten into the ground by his backing band. My hunch is that Dylan, producing in the studio, nods in inscrutable approval when he hears something he likes. The band, nervous but eager to please, obliges and starts playing the damn riff continuously. There’s no outsider around to tweak it or vary it or add dynamics.

In the folk-blues tradition, older songs were reappropriated and built upon; in his later years, Dylan has played with this tradition and found himself in mini-controversies when researchers find that some words in his songs first appeared somewhere else. Amateur sleuths discovered that his album “Love and Theft” had a pattern of lines seemingly taken from a fairly obscure Japanese writer, Junichi Saga. More recently, some obsessives started looking at passages in Chronicles and found lines taken from an astonishing variety of places, from self-help books to The Great Gatsby. The pickings seem to be phrases bouncing around the ragged mind of a guy with a photographic memory. On the other hand, some of the inner workings are plainly mischievous, like an in-passing list of news stories; the headlines were all from a mocking take on the press in John Dos Passos’s U.S.A.

To tweak the purists again, he’ll once in a while appear in a TV commercial—distracting from the subtle attention he pays to how posterity will see his work. He goes out of his away to appear on awards shows when they beckon; he’s shown his artwork and sells it online; his memoir, while odd, was nonetheless transfixing and reminded us that he was once a young man groping for a future and placing his bets on a very long shot indeed. The Dylan camp is readying an extraordinary digital archive of his songs, recordings, and paraphernalia. Dylan owns a coffeehouse, it’s said, in Santa Monica; unprepossessing and iconoclastic, it has an extremely friendly staff and no Wi-Fi. There’s not much on the walls, but you notice the references contained in what’s there: Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, Muhammad Ali, Leonardo da Vinci. There’s one big oil painting behind the counter, one that looks a lot like Dylan’s own work, silent and content in the company it keeps.

And then there’s the touring. In Chronicles, Dylan details, with seeming frankness, the aimlessness that brought him to a slough of despond at the end of the ’80s. He may have been facing what all rock stars who survive face, which is how to grow old gracefully in a medium cruelly tied to youthfulness. He resolved to get out and play his songs—and went back on the road in 1988 with a small, seldom-changing backing ensemble, with whom he delved into his back pages, including many songs he’d never played live before.

Here’s the odd thing—26 years on, he hasn’t stopped. He’s been playing about 100 shows annually ever since, growling through a set of songs old and new with a small band. It’s an endeavor that for a good chunk of each year keeps him on a private bus and, in the U.S. at least, in relatively crummy hotel and motel rooms. (He’s said to prefer places that have windows that open and allow him to sleep with his pet mastiffs. Beyond that, they are places fans wouldn’t expect to find him.) The shows at first may have been a tonic, but over time they revealed themselves to be a panacea. It must have struck Dylan: How could he look foolish if he just kept doing the same thing? If he were an artist, he would continue to create and show his art publicly. If he were a celebrity, he would appear in public. And if he were a seer, a prophet, or even a god, well, he would let folks pay and see for themselves how mortal such figures actually were. And far from saturating the market, he has created a new industry for himself as a touring artist. On a good night he makes some of his best-known songs unrecognizable, and on a bad one you come out wondering what it was, exactly, you’ve just seen. So far this year, the 73-year-old has played in Japan (17 shows), Hawaii (two), Ireland, Turkey, and nearly 20 other cities in the hinterlands of Europe; he’s headed now to more than a dozen shows in eight different cities in Australia and New Zealand—and this is before what should be a fall run through the States. Robert Shelton, the New York Times writer who first noticed Dylan, labored on a biography for more than 20 years; seeing the star’s unstable arc on its publication in 1986, he titled it, grandly, No Direction Home. Dylan hadn’t even begun not to go home.

It strikes me that the one thing all of these bizarre behaviors have in common is that they tend to strip away everything that stands between Bob Dylan’s art and his audience but simultaneously occlude everything else. There was a subtle shift in emphasis in one of his most powerful images, and perhaps a hint of resignation, in the song “

Not Dark Yet,” in 1997:

I was born here and I’ll die here against my will

I know it looks like I’m moving, but I’m standing still

Every nerve in my body is so vacant and numb

I can’t even remember what it was I came here to get away from

Don’t even hear a murmur of a prayer

It’s not dark yet, but it’s getting there

I can’t even remember what it was I came here to get away from. The exultant cry of “no direction home” derived its power from the fact that, in the end, any place new was better than where we’d come from. In that context, not remembering what you left originally is a remarkable statement of anomie.

Still, we might have focused over the years too much on the word direction, as in “heading toward.”

Maybe “no direction home” means that there’s no guidance home, that you have to figure it out for yourself.

If Bob Dylan is a question, maybe this is the answer. Given the chance, Dylan will give the audience his art, unadulterated, as he creates it, and nothing more. He believes it’s a corruption of his art to be directed by someone else’s sensibility. In its own weird way, isn’t this one sacred connection between artist and audience? It might be nicer if he did things differently. It might be more palatable, more commercially successful. (He might be somewhere by now.) This is what ties together his signal creations, his ongoing shows, and even the wretched albums of the ’80s and ’90s; what he does might be sublime and ineffable or yet also coarse and unsuccessful; it is what it is, defined by where it comes from, not what it should be. Even his remoteness is a by-product; it’s what he deserves after having given his all. Call the work art, call it crap, call it Spanish boots of Spanish leather, but in the end it’s the creation of an artist who defies us to ask for something more.

*This article appears in the July 28, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.

Hippie Culture

Hallie Israel and Molly Clark

Overview

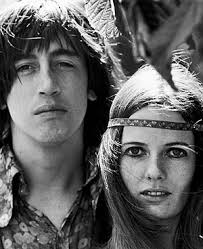

Hippies represent the counterculture of the 1960’s. Their lifestyle is usually associated with rock music, hallucinogenic drugs, and long, flowy hair and clothing. They were seen by some as disrespectful and dirty and a disgrace to society, but to many they are a reminder of a more peaceful, carefree part of America’s history. Hippies were strongly against violence and supported liberal policies and freedom of personal expression, their lifestyles centering around the concepts of peace, freedom, and harmony for all people.

Generally, counterculture is used to describe the culture of a group of people whose morals, values, core ideals, and lifestyle differs, contradicts, or is polar to those of mainstream society at the time. Culturally, it is often described as a social equivalent to extremely liberal politics and radicalism. ideas of hippie culture are listed below:

ideas of hippie culture are listed below:

Who

The hippies of the 1960’s were the teenagers of the baby boom generation, so they were found in large numbers. They were generally Caucasian, middle-class, white teenagers between the ages of 15-25 who were tired of the restrictions put on them by society and their conservative parents. Most lived in urban areas or came from an urban background. They were tired of conforming and began to express themselves in a radical way. Hippies didn’t care about money and worked as little as possible. Instead, many of them shared what they had and lived together in large communes, while others simply lived in poverty by choice. They had very liberal political views and strongly protested the government and the war. The lifestyle of a hippie centered around non-conformity, because hippie culture is all about embracing who you really are and rejecting the need to conform to their society or authorities. Some of the main

-Do not conform to society.

-Materialism is wrong.

-Technology is unnecessary and oftentimes dehumanizing.

-Be your own person, not who anyone else wants you to be.

Although each hippie embraced his or her own ideals as a part of their new culture, the stereotypical hippie:

-Used hallucinogenic drugs.

-Practiced or were interested in Eastern Religions

-Had very liberal political views.

-Peace and love instead of hate and war.

-Expressed extreme tolerance and on the subject of sexuality and sex.

-Live life to the fullest

-Embrace the peace and love expressed by music, as well as the unification it creates among people, usually rock and roll.

What

The culture of hippies was unlike anything the people of the United States had ever seen before. They focused their lives around the ideas of peace, love, freedom, and living life to the fullest. To heighten their experiences spiritually and physically, many hippies used hallucinogenic drugs, like LSD. They listened to rock music and encouraged artistic expression in all different mediums. They lived peaceful lives and believed that living together in harmony was possible and necessary. Because of this, they strongly opposed violence, in particular, the Vietnam War. They believed that the government was the root of this and many other evils in society at the time. Due to this belief in particular, many officials and authorities at the time felt threatened by the prescence and radical ideas expressed by hippie culture and saw them as a danger to society, instead of a peaceful force who disagreed with their way of life. Still however, many authorities at the time felt threatened by the presence and radical ideas expressed by hippie culture.

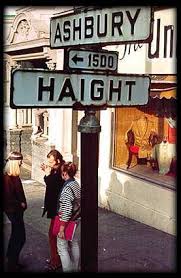

Where

The hippie movement originated in the United States and was seen throughout the country, later spreading through other parts of the world. The main epicenters of it, however, were in the Haight Ashbury district of San Francisco and in the East Village of New York City, which were home to two of the largest hippie communities that ever existed. As the 1960’s progressed, the trend spread to Canada and eventually to many large cities in Western Europe, especially London, Amsterdam, Paris, Berlin and Rome.Although counterculture was often found in urban areas and large cities because of its ability to spread quickly through these densely-populated areas, many also argue that the hippie movement began on college campuses, with liberal students who rejected the social privilege they had been born with because they didn’t agree with the conservative values and political ideals which accompanied it. The hippie movement also spread through cafes and bars, which increasingly became centers of social gathering at the time.

When

The hippie movement first became popular in the 1960’s, with a recognizable decline in the hippie counterculture movement occurring in the late 1970’s due to the aging of the hippie population as well as the end of the Vietnam War.

Why

The hippie counterculture was a social movement caused by many issues and changes going on in the United States during the 1960’s. One important cause was the Vietnam War. These young men and women had friends and brothers being drafted and killed in Vietnam and were looking to make their anti-war views heard, hoping that they could bring peace and harmony to the world in a time of such great violence and atrocity. Another factor influencing hippie counterculture was the increasing popularity of rock and roll music. Rock and roll was a groundbreaking new type of art that encouraged peaceful expression, while also bringing people together and uniting them. The unity of rock music connected many hippies and allowed them to identify and relate with one another through a means that they could all relate to, share, and understand. Many hippies shared their culture through musical concerts and gathering, the most famous of which are Woodstock and the Summer of Love. Also influencing the liberal ideas of hippie culture was a greater access to birth control, which allowed for a women to control whether or not she wanted to get pregnant. This freedom contributed to the liberal sexual ideas of the time, because it eliminated a major consequence of sex and enabled women to attain greater control over their lives without necessarily embracing the safety of conservative values.

Additionally, hippies also had access to mind-altering drugs (hallucinogens) at the time, which greatly contributed to their lifestyle as use of the drugs became more accepted and a part of mainstream culture. Underground newspapers, new types of art (such as op art), rock music, and movies helped to define hippie counterculture and communicate the ideas of these non-conforming liberals.

In the 1960’s hippie counterculture began as the natural reaction for liberals who opposed the culture and conservative society of the 1950’s, the principles of the Cold War, and the violence of the Vietnam War. This rebelliousness of older, conservative lifestyles and values led to the hippie movement in the 60’s as people tried to oppose societal restrictions and ideals forced onto them by the previous generation. Hippie counterculture was a way for these liberals to express their views for peace, freedom, and non-conformity, creating a new culture of own in order to live life by their own ideals and have their voices heard and opinions respected as a group.

see the video below

http://youtu.be/TC3LryTjYqw

Later in the 60’s factors influencing counterculture were tensions between the average citizen and all symbols of authority. There were also many tensions on key issues such as civil rights, womens’ rights, abortion, gay rights, and more. An issue which affected hippie culture was also the atrocities of the Vietnam War, which hippies strongly opposed. Hippies especially opposed the draft into the Vietnam War, believing that the war was wrong and that innocent Americans shouldn’t be forced to fight if doing so was against their moral principles. The liberal work of activists such as Martin Luther King Junior also spurred the hippie movement because it inspired people to stand up for what they believed in and be free to speak their mind and be themselves. Additionally, many also say that the hippie movement was influenced by the assassination of John F. Kennedy, a popular president whose tragic death fueled the political and social unrest of the time.

Legacy

The hippie movement and counterculture began to decline in the late 70’s, especially after the hippie generation grew older and US involvement in the Vietnam War ended, as well as the draft. However, the spirit of hippie culture has largely influenced the world and society today, because of the new ideas it brought to the world and the freedoms it encouraged.

Works CitedTina Loo “hippies” The Oxford Companion to Canadian History. Ed. Gerald Hallowell. Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Infohio – NOACSC. 16 May 2011″youth movement (1960s).” American History. ABC-CLIO, 2011. Web. 13 May 2011.”Hippies and the Counterculture, 1960-1969 (Overview).” American History.

ABC-CLIO, 2011. Web. 13 May 2011.”Hippies and the Counterculture, 1960-1969 (Activity).” American History.

ABC-CLIO, 2011. Web. 13 May 2011.Goodwin, Susan and Becky Bradley . “1960-1969.” American Cultural History. Lone Star

College-Kingwood Library, 1999. Web. 7 Feb. 2011Redmond, Derek. Two Hippies at the Woodstock Festival. Aug. 1969. Wikipedia.

N.p., 31 July 2005. Web. 18 May 2011. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

File:Woodstock_redmond_hair.JPG>.Hippie couple. N.d. Worldwide Hippies. N.p., 18 Jan. 2010. Web. 19 May 2011.

<http://www.worldwidehippies.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/hippies1.jpg>.Epinosa, Eden. Hippie Life. YouTube.com. N.p., 2009. Web. 19 May 2011.

<http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TC3LryTjYqw>. Published to the web by

the YouTube user lovechild909.