SUPERNAW

SUPERNAW

http://youtu.be/0GmbEn6iza8

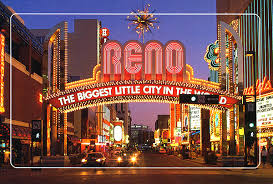

History of Reno

In 1859, Charles Fuller built a log bridge across the Truckee River and charged a fee to those who passed over it on their way to Virginia City and the gold recently discovered there. Fuller also provided gold-seekers with a place to rest, purchase a meal, and exchange information with other prospectors. In 1861, Myron Lake purchased Fuller’s bridge, and with the money from the tolls, bought more land, and constructed a gristmill, livery stable, and kiln. When the Central Pacific Railroad reached Nevada from Sacramento in 1868, Lake made sure that his crossing was included in its path by deeding a portion of his land to Charles Crocker (an organizer of the Central Pacific Railroad Company), who promised to build a depot at Lake’s Crossing. On May 9, 1868, the town site of Reno (named after Civil War General Jesse Reno) was officially established. Lake’s remaining land was divided into lots and auctioned off to businessmen and homebuilders.

The Lake Mansion is one of Reno’s oldest surviving homes. Built in 1877 by William Marsh and purchased by Lake in 1879, the Lake Mansion originally stood at the corner of California and Virginia Streets. In 1971, it was moved to save it from demolition and today the Lake Mansion serves as a small museum on the corner of Arlington Avenue and Court Street.

At the turn of the century, Nevada Senator Francis Newlands played a prominent role in the passage of the Reclamation Act of 1902. The Newlands Reclamation Project diverted Truckee River water to farmland east of Reno, prompting the growth of the town of Fallon.

The residence of Francis Newlands, built in 1889, is one five National Historic Landmarks in Nevada.

Because Nevada’s economy was tied to the mining industry and its inevitable ups and downs, the state had to find other means of economic support during the down times. Reno earned the title “Sin City” because it hosted several legal brothels, was the scene of illegal underground gambling, and offered quick and easy divorces.

Nystrom House, built in 1875 for Washoe County Clerk John Shoemaker, is also significant for its role as a boardinghouse during Reno’s divorce trade in the 1920s. The Riverside Hotel, designed by Frederic DeLongchamps, was built in 1927 specifically for divorce-seekers and boasted an international reputation.

In 1927, in celebration of the completion of the Lincoln Highway (Highway 50) and the Victory Highway (Highway 40), the state of California built the California Building as a gift for the Transcontinental Exposition, held at Idlewild Park.

The Mapes Hotel was built in 1947 and opened for business on December 17th of that year. It was the first high-rise built to combine a hotel and casino, providing the prototype for modern hotel/casinos. The building went vacant on December 17, 1982, 35 years to the day after it opened. The Reno Redevelopment Agency acquired the property in 1996, and sought a developer to revitalize the building. After four years of failed attempts to find a cost-effective way to save the structure, the Mapes was demolished on January 30, 2000.

This brief history of Reno highlights only a few of the many treasures that make up the unique history of “The Biggest Little City in the World.” To own an historic property is to own a piece of a shared history. Because the craftsmanship and fabrication processes that created them are no longer available, historic structures are nonrenewable resources and rely upon the efforts of their owners to ensure they survive into the future.

Museum with Elephant Foot Trash Cans

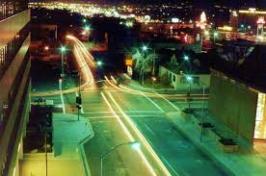

Reno, Nevada

Wilbur May was born rich. He was the youngest son of the owner of the world’s largest department store chain. Dad wanted him to manage his stores, and Wilbur tried to, occasionally. But then he’d vanish for months, off on pleasure trips to China or South America.

That’s what he really liked to do.

When dad died, Wilbur left on a year-long safari and had the dumb luck to cash in all of his company stock for government bonds. The stock market crashed while Wilbur was away, and when he returned he was able to buy 20 times more stock than he’d had when he’d left.

Wilbur took his new millions and moved to Nevada to escape California’s personal income tax. He bought a multi-thousand-acre ranch south of Reno. He kept traveling and killing things. When he died in 1982, the stuff that he’d collected and killed became the Wilbur D. May Museum.

Wilbur had a bottomless appetite for souvenirs. Cases in the museum are crammed with Navajo rugs, Eskimo scrimshaw, African spears, Japanese swords. “Many artifacts that he collected resulted from trades with native people,” reads one sign. “Often, payment was an object that he possessed which the natives coveted.” A quick glance at Wilbur’s booty — Egyptian scarabs, New Guinean masks, T’ang Dynasty pottery — shows who got the better end of those deals.

Wilbur’s prize collectible has to be hishuman shrunken head, a specimen from Ecuador, impaled on a stick, and “used in elaborate cannibalistic rites” according to its sign. Wilbur called the head “Susie” and paid his ranch foreman an extra $5.00 a month to keep its long hair neatly brushed.

Several rooms from Wilbur’s home have been recreated in the museum. The trophy room displays a zoo’s worth of dead animals on its walls: tigers, hippos, rhinos, lions. Ashtrays are made of animal parts, trash cans from elephant’s feet, rifle racks from the upturned legs of gazelles. The furniture is upholstered in zebra, the lamps in giraffe, with bases made of elephant feet and shades probably made of something we’d rather not think about.

“Hunters on safari in Africa were welcomed,” a sign explains, “because the trophies that they collected provided food for hundreds of people.”

The walls of Wilbur’s rebuilt living room showcase his attempts at oil painting, his honorary awards from the Boy Scouts, and a plaque from the staff at one of the May stores, telling Wilbur what a great boss he was. A video about his life loops continually.

On the baby grand piano’s music rack is Wilbur’s proudest creative achievement, the lyrics for “Pass a Piece of Pizza Please,” a 1948 novelty song. A recording of it by Jerry Colonna plays on the room’s old floor model radio:

I don’t want salami, or red meat pastrami

But please won’t you pass a piece of pizza…

Photos on the wall shows bug-eyed Jerry wearing a chef’s hat, hamming it up for the camera with Wilbur.

Wilbur D. May was married four times. Unlike his father, he had no sons to disappoint him. We’d guess, from his museum, that he died a happy man.