Mohamed Choukri, In Tangier

A haven for many Western writers in the twentieth century, Tangier drew the likes of Paul Bowles, Jean Genet and Tennessee Williams. Each was befriended by Mohamed Choukri. This book offers insights into these three cult figures of twentieth-century literature.

WILLIAM BURROUGHS AND JACK KEROUAC AND THE MURDER THAT HELPED

SHAPE THE BEAT MOVEMENT:

Richard Goodman

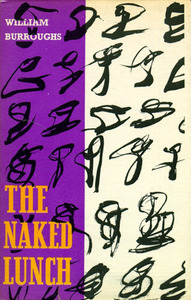

Most followers of the Beats know that Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs and Allan

Ginsberg were friends and kindred souls in New York City in the 1940s. They most likely know

that Burroughs is the character “Bull Lee” in Kerouac’s On the Road and that he appears in two

other Kerouac books. They probably know that Kerouac supplied the title for Burroughs’ most RROUGHScelebrated book, Naked Lunch. (“A frozen moment,” Burroughs writes,” when everyone sees

what is on the end of every fork.”) They may also know that Kerouac and Ginsberg visited

Burroughs in Morocco when Burroughs was living a drug-drenched life there in the 1950s. And

that Kerouac typed out the first two chapters of Naked Lunch for Burroughs who, in Burroughs’

own words, was so drugged out he“could look at the end of my shoe for eight hours.”

What they may not know is that before Morocco, before On the Road, before Naked

Lunch, William Burroughs and Jack Kerouac collaborated on a novel. This novel, And the

Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks, was only published last year—sixty years after it was

written. The book is based on a murder in which Burroughs and Kerouac played minor

supporting, non-lethal roles. However, a case can be made that this murder, and the subsequent

book collaboration, made Burroughs understand that he could write—something he had not

thought of before and had, in fact, disdained.

In other words: no murder, no collaboration—no Naked Lunch.ichard Goodman 2

It all centers around an unlikely character named Lucien Carr, a childhood friend of

William Burroughs’ and a most peculiar fellow.

The facts, more or less, are these. Jack Kerouac, the young man from Lowell,

Massachusetts, had come to New York to attend Columbia University in the early 1940’s.

There, in 1944, he met, first, a young man named Lucien Carr. Then he met Allen Ginsberg, and

then, shortly after, William Burroughs. Here’s how Kerouac himself describes it in the Paris

Review interview, which Kerouac submitted to a year before he died:

First I met Claude [Kerouac’s pseudonym for Lucien Carr]. Then I met Allen and

then I met Burroughs. Claude came in through the fire escape…There were gunshots

down in the alley—Pow! Pow!—and it was raining, and my wife says, “here comes

Claude.” And here comes this blonde guy through the fire escape, all wet. I said,

“What’s this all about, what the hell is this?” He says, “They’re chasing me.” Next day

in walks Allen Ginsberg carrying books. Sixteen years old with his ears sticking out. He

says, “Well, discretion is the better part of valor!” I said, “Aw shutup. You little twitch.”

Then the next day here comes Burroughs wearing a seersucker suit, followed by the other

guy.”

The “other guy” being David Kammerer, about whom you will hear shortly.

Ginsberg, a scrawny kid from New Jersey “with his ears sticking out,” holding a burning

desire to be a genius and a festering guilt about his then unacknowledged homosexuality, was in

awe of the Apollo-like Kerouac. Their relationship would always have an edge to it, with the

twin prejudices against Jews and queers lurking in the back of Kerouac’s mind. The Kerouac

scholar Isaac Gewirtz said that while Kerouac would from time to time in his journals make

cutting remarks about Ginsberg’s homosexuality, he never said a negative word about

Burroughs’ gay proclivities. Burroughs was then living on Bedford Street in Greenwich Village.

The whole lurid drama of David Kammerer and Lucien Carr unfolded in short order. ichard Goodman 3

Lucien Carr—a friend of William Burroughs’ from St, Louis where they had both grown

up—was acknowledged by anyone who met him to be angelically handsome. He was also

strange and manipulative. David Kammerer, an older gay man, and also a childhood friend of

Burroughs’ from St. Louis, was obsessed with the younger Carr. He had been his teacher at one

time and followed him from state to state, hoping for some kind of idealized, or actual,

consummation. When Carr came to New York, so did Kammerer.

Carr seems to have tolerated this obsession and perhaps was even titillated by it. (Isaac

Gewirtz thinks this was because “Carr was a sadist.”) In any event, on the night of August 16th,

1944, on the Upper Side of New York, David Kammerer and Lucien Carr were sitting together in

Riverside Park near Columbia University. This time, apparently, Kammerer, who always

seemed to know at what point to stop his advances, went too far. Lucien Carr stabbed David

Kammerer to death with a pocket knife. He tied Kammerer’s hands and feet together, and threw

the body into the nearby Hudson River. Realizing the grave nature of his deed, Carr first went to

his old friend, William Burroughs, for advice. Burroughs told him to turn himself in. Ignoring

this counsel, Carr went to Jack Kerouac, and Kerouac, for some reason, helped Carr dispose of

the murder weapon.

Carr did finally turn himself in. He was tried and convicted, but he served just two years

in prison for the murder. A homosexual preying on a youth was a very sure defense back then in

court. Kerouac spent a few days in jail for aiding and abetting. He got out by marrying his

girlfriend and having his in-laws post bail. (His own father would not.) Burroughs’ was put in

jail, too, but his father posted bail immediately. ichard Goodman 4

When the dust settled about a year later, Burroughs and Kerouac decided to write a novel

together based on the murder. The two men, along with Edie Parker—Kerouac’s former wife

and intermittent lover—and Joan Vollmer Adams—who Burroughs would later marry and, in

Mexico City, shoot to death—were all living together in an apartment on the West 115th Street.

In August of 1945, Burroughs and Kerouac began writing And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their

Tanks, quite clearly based on the Kammerer murder. Burroughs wrote the first chapter, and then

the two men alternated after that, chapter by chapter. It took them just a month to finish it.

There is no doubt this is a roman à clef. If you’re a stickler about these things, and

demand proof that the novel is, in fact, based on this rather tawdry murder, the proof is in the

New York Public Library. A few short weeks ago I was at the Library visiting the Berg

Collection of English and American Literature. I had before me the second draft, in typescript,

single spaced, on onion paper, of And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks. At this point, it

was called I Wish I Were You. At the top of page one, which is dated August 25, 1945—it’s

quite sobering to think that two atomic bombs were dropped on Japan just two weeks earlier—

are the names of the main characters, in Rosetta Stone-like fashion, deciphered. It says:

Phillip=Lucien [Carr]

Dennison=[William] Burroughs

Ryko=Jack [Kerouac]

Ramsey Allen=Dave K[ammerer]

When the novel was finished, Burroughs and Kerouac tried to get it published, but with

no success. Burroughs didn’t think much of the book. In any case, the men went their separate ichard Goodman 5

ways, literarily and actually, to meet again in Louisiana, Mexico and, in the mid-1950s,

Morocco. They also went on to write their own books and to carve their individual niches in

American literary history. And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks was forgotten, or, more

accurately, was unknown to all but a few people. The book did, however, achieve a kind of

mythical status by those who had heard of it. An unpublished Burroughs/Kerouac manuscript!

Will it ever surface?

James Grauerholtz, the executor of William Burroughs’s estate, promised Lucien Carr—

who, by the way, after he was released from jail, went on to have a long career with United Press

International and is the father of the novelist Caleb Carr—he would not try to get the book

published while he, Lucien Carr, was still alive. When Carr died in 2005, Grauerholtz felt free to

try to get Hippos published and, in 2008, it was, by Grove Press, the American publisher of

Naked Lunch. I should say I don’t think the book is a major literary event—just a curiosity.

However, others do attribute merit to the book. Here’s what Ian Pindar of England’s Guardian

newspaper wrote about the book in late 2008, a month after And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their

Tanks was published:

Neither Burroughs nor Kerouac is at his best here, but Hippos has value as a

testament to their latent talent. Both men, though young, come across as natural writers

with an instinct for the telling detail. Burroughs is grimly fascinated by the abuse of

authority, his sarcastic, petty-minded landlord Mr Goldstein being a distant relative of the

County Clerk in Naked Lunch. If anything, Hippos proves that becoming a junkie was the

making of Burroughs, pulling his unique vision into focus.

Now you can read the book and see for yourself:ichard Goodman 6

You might be curious as to the genesis of the title. According to Kerouac, “Burroughs

and I were sitting in a bar one night and we heard a newscaster saying [remember, this is during

wartime], ‘….and so the Egyptians attacked blah blah blah…and meanwhile there was a great

fire in the zoo in London and the fire raced across the fields and the hippos were boiled in their

tanks! Good night everyone!’” Burroughs caught that and suggested it as a title. He and

Kerouac went through a few titles—I Wish I Were You being one of them—but finally decided

on And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks.

I met Burroughs in 1971 and spent time with him in London and in New York. That

affects my response to Kerouac’s description of Burroughs in On the Road and, especially, in

Vanity of Duluoz. Burroughs was nine years older than Kerouac—although you will read in

some biographies that he was eight years older—something that surprised me. (Kerouac wrote,

“He was nine years older than me but I never noticed it.”) I think it surprised me because

Burroughs always looked old, even when he was young, and Kerouac, when he was young,

looked like the epitome of youth. This is how Kerouac describes that first meeting with

Burroughs, or “Will Hubbard,” in Vanity of Duluoz:

When I had heard about “Will Hubbard” I had pictured a stocky dark-haired

person of peculiar intensity because of the reports about him, the peculiar directness of

his actions, but here had come walking into my pad tall and bespectacled and thin in a

seersucker suit as tho he’s just returned from a compound in Equatorial Africa where

he’d sat at dusk with a martini discussing the peculiarities… Tall, 6 foot 1, strange, ichard Goodman 7

inscrutable because ordinary-looking (scrutable), like a shy bank clerk with a patrician

thin-lipped cold bluelipped face, blue eyes saying nothing behind steel rims and glass,

sandy hair, a little wispy, a little of the wistful German Nazi youth as his soft hair fluffles

in the breeze….

Well, I am here to tell you, having met William Seward Burroughs, that this description

is spot on, the best physical description of Burroughs I have ever read and one that captures him

perfectly. I feel as if he’s stepping right out of the page when I read this, and it brings me back

to that day, in 1971, when, as a young man, I nervously knocked on the door of Burroughs’ Duke

Street flat in London, and William S. Burroughs himself opened the door to let me in. But I want

to go forward a bit to quote another passage to show you that Kerouac could not only describe

Burroughs’ appearance, but his mind and spirit and his character, as well. Kerouac understood

that, though he called Burroughs “a teacher,” their relationship was not one-sided at all. Here’s

what Kerouac writes about those early days in New York,

I think it was about then he [Hubbard/Burroughs] rather vaguely began to admire

me, either for virile independent thinking, or ‘rough trade’ (whatever they think), or

charm, or maybe broody melancholy philosophic Celtic unexpected depth or simple

ragged shiny frankness…

In fact, everything Kerouac writes about Burroughs, and about the two of them, is

powerful and pristine—and, above all, generous. Here’s one of his rhapsodies in Vanity of

Duluoz:

O Will Hubbard in the night! A great writer today, he is a shadow hovering over

Western literature, and no great writer ever lived without that soft and tender curiosity,

verging on the maternal care, about what others think and say, no great writer ever

packed off from this scene on earth without amazement like the amazement he felt

because I was myself.ichard Goodman 8

I won’t linger too much more on physical descriptions, only to say that in On the Road,

Burroughs—or “Old Bull Lee”—comes across as much more of an eccentric shaman. Of course,

On the Road was written many years earlier than Vanity of Duluoz.. The narrator visits Bull Lee

at his farm in Algiers, Louisiana, outside of New Orleans on his cross-country ride. “It would

take all night to tell about Old Bull Lee,” the narrator begins. Then, later, he says, “He [Bull

Lee] spent all his time talking and teaching others. Jane [the actual name of Burroughs’ wife] sat

at his feet; so did I.” Kerouac goes on to replicate some of the quirky, wonderful speech of

Burroughs’ during their stay with him. He speaks as well about sitting at Burroughs’ feet in his

journal.

By the way, “Lee,” as in Old Bull Lee, is a pseudonym Burroughs himself used for his

first book, Junky, published in 1953 by Ace Books. So volatile was the subject matter at the

time—a book written by a dope fiend!—that Burroughs felt compelled to use his mother’s

maiden name, Lee, for his own. So the very first edition of Junky is by “William Lee.”

The fact is this: fairly soon after they met in New York, Jack Kerouac and William

Burroughs wrote a book together. It was clear that Burroughs, a Harvard graduate who had

studied medicine in Vienna and had a wide-ranging mind, was the better educated man, certainly

from the point of view of certain kinds of reading and exposure to the world. Kerouac had no

problem at all acknowledging that Burroughs taught him a great deal in that area. In Vanity of

Duluoz, Kerouac describes one such instructional moment,

Harbinger of the day when we’d become fast friends and he’d hand me the full

two-volume edition of Spengler’s Decline of the West and say ‘EEE dif y your mind, my

boy, with the grand actuality of Fact.’ When he would become my great teacher in the

night.ichard Goodman 9

If anyone had more experience as a writer at that point, though, it was Jack Kerouac, the

younger man. (Kerouac was twenty-three at the time, Burroughs, thirty-two.) Not only that,

Burroughs did not think of himself as literary, much less a writer. He abhorred the very idea.

Kerouac at this point had a strong yearning to be a writer and was already writing the book that

would become The Town and the City, his first published novel. In short, Kerouac knew he

wanted to be a writer even then, at twenty-three, and even before. Burroughs had no idea, and no

desire.

There is a wonderful little book titled Photos and Remembering Jack, by Burroughs,

published by White Fields Press in 1994. The photos are by Allen Ginsberg. In the photographs,

we see Burroughs is an old man, bent over, with a cane, but still vigorous, at one point rowing a

boat. There are only two short passages in the book. In the first, Burroughs wrote, simply, “Jack

Kerouac was a writer. That is, he wrote…. He went there and wrote it and brought it back for a

generation to read, but he never found his own way back. A whole migrant generation arose

from Kerouac’s On the Road….”

So whereas Kerouac’s feelings toward Burroughs were somewhat worshipful, it may be

said, as Isaac Gewirtz notes in his fine book, Beatific Soul: Jack Kerouac on the Road,

Burroughs credits Kerouac for his writing career. Gewirtz quotes an essay by Burroughs titled,

“Jack Kerouac,” in which he, Burroughs, elaborates on this:

It was Kerouac who kept telling me I should write and call the book I wrote

Naked Lunch. I had never written anything after high school and did not think of myself

as a writer and I told him so… “I got no talent for writing…” He insisted quietly that I

did have talent for writing and that I would wrote [sic] a book called Naked Lunch To

which I replied “I don’t want to hear anything literary.” He just smiled. In fact during all ichard Goodman 10

the years I knew Kerouac I cant remember ever seeing him really angry or hostile. It was

the sort of smile in a way you get from a priest who knows you will come to Jusus sooner

or later…”

Gewirtz reconfirmed the importance of Kerouac’s influence on Burroughs. “Burroughs

always acknowledged that Kerouac was the reason he became a writer,” he said. “He never had

a qualm about that.”

So what I am getting at here is that Burroughs’ influence on Kerouac is probably less

than we think and Kerouac’s influence on Burroughs is probably a lot more than we think. This

is surely not the popular consensus. Burroughs was a very powerful personality, and I can tell

you he was quite formidable in person. He was forbidding and formal—not rude or

discourteous, but just, well, awesome, in the original sense of the word. Kerouac was a very

powerful personality, but his power was of a different sort. It derived from a strong life force. I

think there has come down the notion that Kerouac was much more the absorber, and this is

partially reinforced by the narrator’s role in On the Road, which is, basically, one of hero

worship of Dean Moriarty—i.e., Neal Cassidy. But the evidence points us to another, more

equable conclusion.

I think, in the end, we can say that without Jack Kerouac there may never have been a

Naked Lunch. But I’m not sure that we can say without William Burroughs there never would

have been an On the Road. I believe the book would still have been written—without “Old Bull

Lee” in it, of course, but Dean Moriarty would still be there, and Moriarty is the heart of that

book. It’s all an exercise in literary gamesmanship, though. The good thing is, we do have both

books—however they got written. That’s all that matters.

THE FLOWERING OF the Beat Generation in the late fifties was the result of a very slow germination process. The four original Beats, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, and Neal Cassady, met in New York in the late forties. More than a decade would pass before Ginsberg’s Howl ignited the explosion that would coalesce the disparate ideas, the sense of lifestyle, and the philosophical musings into a full-fledged literary movement.

THE FLOWERING OF the Beat Generation in the late fifties was the result of a very slow germination process. The four original Beats, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, and Neal Cassady, met in New York in the late forties. More than a decade would pass before Ginsberg’s Howl ignited the explosion that would coalesce the disparate ideas, the sense of lifestyle, and the philosophical musings into a full-fledged literary movement.