Read more http://www.scoopnest.com/user/designtaxi/666209285534302208#qY7lrF40hxmStX3I.99

image:

Read more http://www.scoopnest.com/user/designtaxi/666209285534302208#qY7lrF40hxmStX3I.99

image:

Charlie Hebdo artist “Luz”, who designed the satirical magazine’s front page after the Paris attacks, says he will no longer draw the Prophet Muhammad.

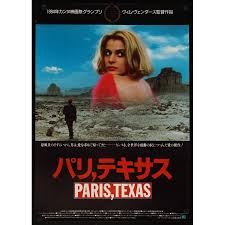

Paris, Texas The Observer

Harry Dean Stanton: ‘Life? It’s one big phantasmagoria’

The wine, the women, the song… The great Harry Dean Stanton talks to Sean O’Hagan about jogging with Dylan, Rebecca de Mornay leaving him for Tom Cruise and why Paris, Texas is his greatest film

Harry Dean Stanton

Harry Dean Stanton: ‘I surrender to acting in the same way I surrender to life’ Photograph: Steve Pyke

Sean O’Hagan

Saturday 23 November 2013 15.00 EST Last modified on Thursday 22 May 2014 05.00 EDT

Harry Dean Stanton is singing “The Rose of Tralee”. His wavering voice echoes across the rows of people gathered in the Village East cinema in New York, where a special screening of a new documentary about his life and work, Partly Fiction, has just finished. You can tell that the director, Sophie Huber, and the cinematographer, Seamus McGarvey, who are sitting beside him, are used to this sort of thing from Harry, but the rest of us are by turns delighted and a little bit nervous on his behalf. Now that he’s 87, Stanton’s voice is as unsteady as his gait, but he steers the old Irish ballad home in his inimitable manner and the audience responds with cheers and applause.

“Singing and acting are actually very similar things,” says Stanton when I ask him about his other talent, having seen him perform about 15 years ago with his Tex-Mex band in the Mint Bar in Los Angeles. “Anyone can sing and anyone can be a film actor. All you have to do is learn. I learned to sing when I was a child. I had a babysitter named Thelma. She was 18, I was six, and I was in love with her. I used to sing her an old Jimmie Rodgers song, ‘T for Thelma’.” Closing his eyes, he breaks into song: “T for Texas, T for Tennessee, T for Thelma, that girl made a wreck out of me.” He smiles his sad smile. “I was singing the blues when I was six. Kind of sad, eh?”

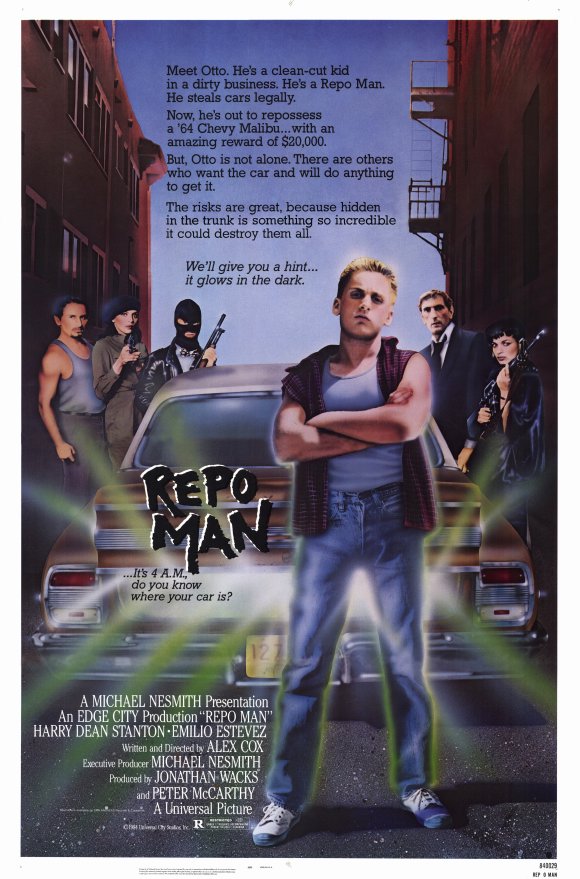

There is indeed a peculiar kind of sadness about Harry Dean Stanton, a mix of vulnerability, honesty and seeming guilelessness that has lit up the screen in his greatest performances. It’s there in his singing cameo in 1967’s prison movie Cool Hand Luke, in his leading role in Alex Cox’s underrated cult classic Repo Man in 1984 and, most unforgettably, in his almost silent portrayal of Travis, a man broken by unrequited love in Wim Wenders’s classic, Paris, Texas. “After all these years, I finally got the part I wanted to play,” Stanton once said of that late breakthrough role. “If I never did another film after Paris, Texas I’d be happy.”

Now, with mortality beckoning, Stanton still gives off the air of someone who, as he puts it, “doesn’t really give a damn”. In his room in a hip hotel on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, the aircon is on full blast despite his runny nose and troubling cough, and he smokes like a train as if oblivious to the law and the health police. He looks scarecrow thin, but dapper, in his western suit, embroidered shirt and ornately embossed cowboy boots: a southern dandy even in old age. His hearing is not so good, but his voice remains unmistakable, that soft trace of his southern upbringing in rural Kentucky still detectable. “I’ve worked with some of the best of them,” he says. “Not just directors like Sam Peckinpah and David Lynch, but writers like Sam Shepard and singers like Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson and Kris Kristofferson. I could have made it as a singer, but I went with acting, surrendered to it, in a way.”

Paris Texas

Harry Dean Stanton in 1984’s Paris, Texas – the film of which he is most proud. Photograph: Ronald Grant Archive

Before Paris, Texas, Stanton had appeared in around 100 films and since then he has acted in more than 50 more, though often as a supporting actor. The lead roles did not materialise in the way he expected them to, perhaps because he is so singular, both in looks and acting ability. When given the right script and a sympathetic director, though, he is as charismatic as anyone, as his role in David Lynch’s The Straight Story showed. Recently he has shone fitfully in Martin McDonagh’s Seven Psychopaths, and in the HBO series Big Love as a self-proclaimed Mormon prophet. He has also appeared in action pics such as The Last Stand with Arnie Schwarzenegger and in the Marvel blockbuster Avengers Assemble. He appears not to care too much about the kind of fame and huge earning power that other actors without an iota of his onscreen presence command.

“Harry is a walking contradiction,” says Huber, who has known him for 20 years. “He has this pride in appearing to not have to work hard to be good. He definitely does not want to be seen to be trying. It’s part of his whole Buddhist thing.” His worldview is a mixture of various Buddhist and other more esoteric eastern philosophies, shaped in the late 60s by the writings of Alan Watts, the Beat poet and Zen sage, and adapted over the years to suit Stanton’s singular, slightly eccentric lifestyle.

Lately, though, at screenings of Huber’s documentary, he has reacted angrily to Wim Wenders’s onscreen observation that Stanton was insecure about playing the lead role in Paris, Texas. “I asked him: ‘Harry, how come you are angry at that scene? I thought you didn’t have an ego,'” says Huber. “He just nodded and said: ‘Yeah, I guess I should shut up.’ But it had obviously got to him.”

Stanton tells me more than once that he has no ego and no regrets, but you have to wonder if that is true. He is, as Partly Fiction shows, a kind of lone drifter in Hollywood, perhaps the last of that generation of great American postwar character actors, and certainly one of the most singular.

Back in the late 60s, he shared a house in Hollywood with Jack Nicholson, and they partied hard with the David Crosby, Mama Cass Elliot and the burgeoning Laurel Canyon rock aristocracy of the time. Now, still an unrepentant bachelor, he speaks fondly on camera about the great lost love of his life, the actor Rebecca de Mornay – “She left me for Tom Cruise.”

Harry Dean Stanton: Partly Fiction

Harry Dean Stanton with Sophie Huber, the director of Partly Fiction. Photograph: Michael Buckner/Getty Images

When a wag in the audience asks him what Debbie Harry was like “in the sack”, he shoots back: “As good as you think!” adding that the Nastassja Kinski was pretty good, too.

Advertisement

Stanton spends most evenings, when he is not working in Dan Tana’s bar in East Hollywood, drinking with a small bunch of regulars and telling anyone who can’t quite place his face that he is a retired astronaut. “He’s an outsider but has lots of good friends,” says Huber. “He’s happy compared to most 87-year-olds. He says he doesn’t care about dying, but some days, I suspect, he thinks about it a lot. You never really know what’s going on in his head.”

This is exactly how Stanton likes it, of course. In Huber’s slow, almost meditative film, Stanton looms large while revealing little. The New York Times reviewer concluded: “You won’t learn much, but you’ll be strangely happy that you didn’t.” Stanton quotes the line back to me, grinning. “She got it,” he says approvingly. “That’s a very Buddhist thing to say.”

Huber describes Partly Fiction as “a portrait of his face” and those expressive eyes and weathered features, shot close-up in black and white by McGarvey’s luminous cinematography, do indeed speak volumes about how Stanton has made silence and stillness his most powerful means of onscreen communication. There is a great scene where David Lynch, his equal in eccentricity, talks about what Stanton does “in between the lines” and how he is “always there – whatever ‘there’ needs to be”.

Stanton smiles when I mention it. “I guess he was talking about being still and listening. Being attentive even when it’s not your line. For me, acting is not too different from what we are doing right now. We’re acting in a way, but we are not putting on an act. That’s the crucial difference for me. I just surrender to it in much the same way I surrender to life. It’s all one big phantasmagoria anyway. In the end I’ve really got nothing to do with it. It just happens, and there’s no answer to it.”

Harry Dean Stanton with Jack Nicholson. The two actors shared a house in Hollywood in the 60s. Photograph: Rex Features

In all kinds of ways, Stanton has travelled lunar miles from his smalltown upbringing in East Irvine, Kentucky. Born in 1926, he is the eldest of three sons to Ersel, who worked as a hairdresser, and Sheridan, a tobacco farmer and Baptist. Stanton describes his childhood as strict and unhappy. “My father and mother were not that compatible. She was the eldest of nine children and she just wanted to get out. I don’t think they had a good wedding night, and I was the product of that. We weren’t close. I think she resented me when I was a kid. She even told me once how she used to frighten me when I was in the cradle with a black sock.”

He laughs soundlessly but looks unbearably sad. “I brought all that stuff up with her just after I started seeing a psychiatrist. I did group therapy and all that and it all came out. So I called her one night and told her I hated her.” He shakes his head and smiles ruefully. “We made up shortly before she died. Got pretty close then, actually. That’s how it goes sometimes.”

Was acting in some way an attempt to escape that grim childhood?

“Yes, I guess so. You can do stuff onstage that you can’t do offstage. You can be angry as hell and enraged and get away with it onstage, but not off. I had a lot of rage for a time, but I let go of all that stuff a long time ago.”

Stanton served in the US Navy during the Second World War, working as a ship’s cook. “Most actors don’t have that kind of life experience now,” he says matter-of-factly. “I was lucky not to have been blown up or killed. I was there when the Japanese suicide planes were coming in. Fortunately they missed our boat. Took me a while to readjust after I went back home and went to college in Lexington, Kentucky.” There he started acting in the college drama group while studying journalism. “I acted in Pygmalion with a Cockney accent. I knew right then what I wanted to do, so I quit college and went to the Pasadena Playhouse in 1949.”

He landed his first job after answering a “singers wanted” advert in the local paper and toured for a while with a 24-piece choral group. “Twenty-four guys on a bus playing small towns. When I quit, there were only 12 guys left. The rest deserted along the way. We sang on street corners, in department stores and, at the end of a week, in a local venue. It’s called paying your dues.”

The dues-paying continued with myriad supporting roles on television in the 1950s, including appearances in popular western series such as Wagon Train and Gunsmoke. In 1967 he had a brief, but resonant, role as a guitar-strumming convict in Cool Hand Luke, starring Paul Newman. By the early 1970s, he had become a cult actor courtesy of two indie classics directed by the mercurial Monte Hellman: Two-Lane Blacktop and Cockfigher. In the former he befriended the singer James Taylor, who wrote a song, “Hey Mister, That’s Me Up On The Jukebox”, on Harry’s favourite guitar. He later befriended Bob Dylan during the famously difficult shoot for Sam Peckinpah’s elegiac western Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid in 1973. “Dylan and I got to be very close. We recorded together one time. It was a Mexican song. He offered me a copy of the tape and I said no. Shot myself in the foot. It’s never seen the light of day. I’d sure love to hear it.”

In Partly Fiction (which has yet to get a UK release date), Kris Kristofferson, who played the lead in that film, recalls Peckinpah throwing a knife in anger at Stanton when the actor messed up a crucial scene by running through the shot. “As I recall, he pulled a gun on me, too. It was because me and Dylan fucked up the shot.”

On purpose? “No, we were jogging and we ran right across the background.” The vision of Dylan and Stanton jogging together seems altogether too absurd, but I let it pass. He describes Peckinpah as “a fucking nut, but a very talented nut”. Likewise the maverick British director Alex Cox, who cast him in Repo Man in 1984. “He was another nut. Brilliantly talented and a great satirist, but an egomaniac.”

That same year, Stanton made Paris, Texas, and created his most iconic role. “It’s my favourite film that I was in. Great directing by Wenders, great writing by Sam Shepard, great cinematography by Robby Müller, great music by Ry Cooder. That film means a lot to a lot of people. One guy I met said he and his brother had been estranged for years and it got them back together.”

Does he think he should have had bigger, better roles in the years since? He lights up another cigarette and stares into the middle distance, lost in some private reverie. “You get older,” he says finally. “In the end, you end up accepting everything in your life – suffering, horror, love, loss, hate – all of it. It’s all a movie anyway.”

He closes his eyes and recites a few lines from Macbeth, sounding suddenly Shakespearean, albeit in his own wavering way. “A tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” He opens his eyes again. “Great line, eh?” he says, smiling and reaching for a cigarette. “That’s life right there.”

Hover over a country below to view its press freedom score.*

Green = Free

Yellow = Partly Free

Purple = Not Free

* Score out of 100. The lower the score, the better the press freedom status.

CLICK HERE for booklet. CLICK HERE for booklet. |

Only 1 in 7 people live in a country with a ‘free’ press.

Global press freedom has fallen to its lowest level in over a decade, according to the latest edition of Freedom House’s press freedom survey. The decline was driven in part by major regression in several Middle Eastern states, including Egypt, Libya, and Jordan; marked setbacks in Turkey, Ukraine, and a number of countries in East Africa; and deterioration in the relatively open media environment of the United States.

Freedom of the Press 2014 found that despite positive developments in a number of countries, most notably in sub-Saharan Africa, the dominant trends were reflected in setbacks in every other region.

TABLE OF COUNTRIES: |

TABLE OF CONTENTS: Press Release Press Release (Russian) Map of Press Freedom Overview Essay Overview Essay (Russian) Methodology Charts and Graphs Acknowledgements |

Click on the second tab below for reports on individual countries and territories. Territories are identified with asterisks.

His novel is at the top of the Amazon bestsellers list, nearly 90 years later after it was written. He’s widely considered one of America’s greatest novelists and his work has inspired writers ever since he was published. So then why is F. Scott Fitzgerald, who is more famously associated with places such as Paris, New York and the French Riviera, buried near a highway surrounded by concrete strip malls in Rockville, Maryland?

Beyond the train tracks, with glum office buildings in the backdrop beneath a gravestone that looks like any other, the celebrated novelist, although not in this case, is laid to rest with his wife Zelda. Most local commuters that pass the cemetery probably aren’t even aware that the author is buried there. The only thing about Fitzgerald’s grave that would attract anyone’s attention would be the unusual items occasionally placed on it by visitors– bottles of alcohol and coins; the two things he needed the most before he died.

F. Scott Fitzgerald died of a heart attack in 1940 in Hollywood California at his lover’s apartment. At the time he was utterly broke and considered himself a failure. Years of excessive drinking since his college years had left him in poor health and after the Great Depression, readers nor publishers were interested in stories of the glitzy Jazz Age. By the time of his death, you would be lucky to find a copy of The Great Gatsby on bookstore shelves. Because of his adulterous relationship and the notorious lifestyle he was known to have lived, F. Scott was considered a non practicing Catholic and denied the right to be buried on the family plot. Only around 25 people attended the rainy funeral at Rockville Union Cemetary and the Protestant minister who performed the ceremony allegedly had never ever heard of him. Almost as if it had been foreshadowed in the book, Fitzgerald’s sadly unsensational farewell was in fact very similar to that of his description of his own character’s funeral, Jay Gatsby.

F. Scott Fitzgerald died of a heart attack in 1940 in Hollywood California at his lover’s apartment. At the time he was utterly broke and considered himself a failure. Years of excessive drinking since his college years had left him in poor health and after the Great Depression, readers nor publishers were interested in stories of the glitzy Jazz Age. By the time of his death, you would be lucky to find a copy of The Great Gatsby on bookstore shelves. Because of his adulterous relationship and the notorious lifestyle he was known to have lived, F. Scott was considered a non practicing Catholic and denied the right to be buried on the family plot. Only around 25 people attended the rainy funeral at Rockville Union Cemetary and the Protestant minister who performed the ceremony allegedly had never ever heard of him. Almost as if it had been foreshadowed in the book, Fitzgerald’s sadly unsensational farewell was in fact very similar to that of his description of his own character’s funeral, Jay Gatsby.

The day for Gatsby’s funeral arrives and the attendees include myself, Gatsby’s father, Owl Eyes, and Gatsby’s servants. How could a man of such status have such a pathetic and depressing last farewell?

–The Great Gatsby

It wasn’t until 35 years later that Catholic St. Mary’s cemetery just up the road, accepted both the Fitzgeralds into the family plot you see pictured here (Zelda later died in a fire in 1948 and was buried with him), a small step up from the forgotten grave at the Rockville Union cemetery.

The stone lifts a quote from his famous novel with his full name inscribed, Francis Scott Key, the name he was given after a distant relative and Maryland native, who also happened to be the author who wrote “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

As the highly anticipated new film adaptation hits cinemas this month, the Reverend Monsignor Amey of St. Mary’s Catholic Church tells the post that the gravesite has been receiving more visitors than usual. “We usually see a handful of people visiting the cemetery in a given week … That number has tripled in the last week,” he told the Washington Post. “Aspiring authors leave pens, and admirers occasionally write handwritten notes. A top hat, adorned with a martini glass ribbon, is the most recent addition.”

Perhaps some of that box-office money should go towards giving this great American writer the resting place he deserves?

Information on Visiting Fitzgerald’s Grave Here

Via Kuriositas and NPR

From Wikipedia:

Brion Gysin (January 19, 1916 – July 13, 1986) was a painter, writer, sound poet, and performance artist born in Taplow, Buckinghamshire. He is best known for his discovery of the cut-up technique used by William S. Burroughs. With Ian Somerville he invented the Dreamachine, a flicker device designed as an art object to be viewed with the eyes closed. It was in painting, however, that Gysin devoted his greatest efforts, creating calligraphic works inspired by Japanese and Arabic scripts. Burroughs later stated that “Brion Gysin was the only man I ever respected.”

John Clifford Brian Gysin was born at Taplow House, England, a Canadian military hospital. His mother, Stella Margaret Martin, was a Canadian from Deseronto, Ontario. His father, Leonard Gysin, a captain with the Canadian Expeditionary Force, was killed in action eight months after his son’s birth. Stella returned to Canada and settled in Edmonton, Alberta where her son became “the only Catholic day-boy at an Anglican boarding school.” Graduating at fifteen, Gysin was sent to Downside in Bristol, England, a prestigious college known as “the Eton of Catholic public schools” run by the Benedictines.

In 1934, he moved to Paris to study La Civilisation Française, an open course given at the Sorbonne where he made literary and artistic contacts through Marie Berthe Aurauche, Max Ernst’s first wife. He joined the Surrealist Group and began frequenting Valentine Hugo, Leonor Fini, Salvador Dalí, Picasso and Dora Maar. A year later, he had his first exhibition at the Galerie Quatre Chemins in Paris with Ernst, Picasso, Hans Arp, Hans Bellmer, Victor Brauner, Giorgio de Chirico, Dalí, Marcel Duchamp, René Magritte, Man Ray and Yves Tanguy. On the day of the preview, however, he was expelled from the Surrealist Group by André Breton who ordered the poet Paul Éluard to take down his pictures. Gysin was 19 years old. His biographer, John Geiger, suggests the arbitrary expulsion “had the effect of a curse. Years later, he blamed other failures on the Breton incident. It gave rise to conspiracy theories about the powerful interests who seek control of the art world. He gave various explanations for the expulsion, the more elaborate involving ‘insubordination’ or lèse majesté towards Breton.”

After serving in the U.S. army during World War II, Gysin published a biography of Josiah “Uncle Tom” Henson titled, To Master a Long Goodnight: The History of Slavery in Canada (1946). A gifted draughtsman, he took an 18-month course in Japanese language studies and calligraphy that would greatly influence his artwork. In 1949, he was among the first Fulbright Fellows. His goal: to research the history of slavery at the University of Bordeaux and in the Archivos de India in Seville, Spain, a project that he later abandoned. He moved to Tangier, Morocco after visiting the city with novelist and composer Paul Bowles in 1950.

In Tangier, Gysin co-founded with Mohamed Hamri a restaurant called “The 1001 Nights” with the Master Musicians of Joujouka from the village of Jajouka. The musicians performed there for an international clientèle that included William S. Burroughs. Losing the business in 1958, he returned to live in Paris, taking lodgings in a flophouse located at 9 rue Gît-le-Coeur that would become famous as the Beat Hotel. Working on a drawing, he discovered a Dada technique by accident:

William Burroughs and I first went into techniques of writing, together, back in room No. 15 of the Beat Hotel during the cold Paris spring of 1958… Burroughs was more intent on Scotch-taping his photos together into one great continuum on the wall, where scenes faded and slipped into one another, than occupied with editing the monster manuscript… Naked Lunch appeared and Burroughs disappeare. He kicked his habit with apomorphine and flew off to London to see Dr Dent, who had first turned him on to the cure. While cutting a mount for a drawing in room No. 15, I sliced through a pile of newspapers with my Stanley blade and thought of what I had said to Burroughs some six months earlier about the necessity for turning painters’ techniques directly into writing. I picked up the raw words and began to piece together texts that later appeared as “First Cut-Ups” in Minutes to Go.

When Burroughs returned from London in September 1959, Gysin not only shared his discovery with his friend but the new techniques he had developed for it. Burroughs then put the techniques to use while completing Naked Lunch and the experiment dramatically changed the landscape of American literature. Gysin helped Burroughs with the editing of several of his novels including Interzone, and wrote a script for a film version of Naked Lunch which was never produced. The pair collaborated on a large manuscript for Grove Press titled The Third Mind but it was determined that it would be impractical to publish it as originally envisioned. The book later published under that title incorporates little of this material. Interviewed for The Guardian in 1997, Burroughs explained that Gysin was “the only man that I’ve ever respected in my life. I’ve admired people, I’ve liked them, but he’s the only man I’ve ever respected.” In 1969, Gysin completed his finest novel, The Process, a work judged by critic Robert Palmer as “a classic of 20th century modernism.”

A consummate innovator, Gysin altered the cut-up technique to produce what he called permutation poems in which a single phrase was repeated several times with the words rearranged in a different order with each reiteration. An example of this is “I don’t dig work, man/Man, work I don’t dig.” Many of these permutations were derived using a random sequence generator in an early computer program written by Ian Sommerville. Commissioned by the BBC in 1960 to produce material for broadcast, Gysin’s results included “Pistol Poem”, which was created by recording a gun firing at different distances and then splicing the sounds. That year, the piece was subsequently used as a theme for the Paris performance of Le Domaine Poetique, a showcase for experimental works by people like Gysin, François Dufrêne, Bernard Heidsieck, and Henri Chopin.

With Sommerville, he built the Dreamachine in 1961. Described as “the first art object to be seen with the eyes closed”, the flicker device uses alpha waves in the 8-16 Hz range to produce a change of consciousness in receptive viewers.

He also worked extensively with noted jazz soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy.

As a joke, Gysin contributed a recipe for marijuana fudge to a cookbook by Alice B. Toklas; it was unintentionally included for publication, becoming famous under the name Alice B. Toklas brownies.

A heavily edited version of his novel, The Last Museum, was published posthumously in 1986 by Faber & Faber (London) and by Grove Press (New York).

Made an American Commander of the French Order of Arts and Letters in 1985, Gysin died a year later of lung cancer on July 13, 1986. An obituary by Robert Palmer published in The New York Times fittingly described him as a man who “threw off the sort of ideas that ordinary artists would parlay into a lifetime career, great clumps of ideas, as casually as a locomotive throws off sparks.”

In a 1966 interview by Conrad Knickerbocker for The Paris Review, William S. Burroughs explained that Brion Gysin was, to his knowledge, “the first to create cut-ups.”

INTERVIEWER: How did you become interested in the cut-up technique? BURROUGHS: A friend, Brion Gysin, an American poet and painter, who has lived in Europe for thirty years, was, as far as I know, the first to create cut-ups. His cut-up poem, Minutes to Go, was broadcast by the BBC and later published in a pamphlet. I was in Paris in the summer of 1960; this was after the publication there of Naked Lunch. I became interested in the possibilities of this technique, and I began experimenting myself. Of course, when you think of it, The Waste Land was the first great cut-up collage, and Tristan Tzara had done a bit along the same lines. Dos Passos used the same idea in ‘The Camera Eye’ sequences in USA. I felt I had been working toward the same goal; thus it was a major revelation to me when I actually saw it being done.

Influence

Gysin’s wide range of radical ideas became a source of inspiration for Beat Generation artists and their successors such as David Bowie, Keith Haring, Brian Jones, Mick Jagger, Genesis P-Orridge, Iggy Pop, Laurie Anderson, Malay Roy Choudhury, and Into A Circle.

A DOCUMENTARY-BRION GYSIN

|

“Degenerates are not always criminals, anarchists, and pronounced lunatics; They are often authors and artists.”

-Max Nordan, Degeneration |

|

Using revolutionary Paris as their backdrop, bohemians challenged the status quo by rejecting mainstream values and mocking the bourgeoisie. However, Bohemia remains difficult to define. Participants, including writers, artists, students and youth, all contributed to the feelings and ideas of bohemia in different ways; the one attribute they shared was their rejection of the bourgeoisie. The image above, Octave Tassaert’s The Studio, was painted in 1845, almost synonomously with the birth of bohemian Paris. This image is a wonderful representation of bohemia, with the young artist working intently in his messy, unfurnished apartment. Despite his long hair and ragged clothes, he is content to be working on the art that he loves. This is the true essence of bohemia. |

http://www.cnn.com/2013/09/22/world/europe/air-france-cocaine-found/index.html

counterculture,alternative news,art

Share something you learned everyday!

Where dead fingers type

Cigarman501

thoughts on writing, travel, and literature

Holistic Wellness: Your Health, Your Life, Your Choice

Back to the island...

My everyday thoughts as they come to me

BY GRACE THROUGH FAITH

Taos, New Mexico

GLOB▲L - M▲G▲ZINE

the world of art

Your psychedelic travel guide around the globe

Just another WordPress.com weblog

Art Works

A World Where Fantasies Are Real And Dreams Do Come True

The WWII US Navy career of my father, Red Stahley, PT boat radioman.

Hiking with snark in the beautiful Pacific Northwest 2014 - 2018

Photos, art, and a little bit of lit....

I wish I'd been born seven hours earlier

A Journey of Self-Discovery & Adventure

Exploring Best Indian Destinations for You

remember what made you smile

Comics und andere Werke des Künstlers Denis Feuerstein

Bit of this, bit of that

Diary of a Shipwrecked Alien

Music In The Key Of See

Fe2O3.nH2O photographs

Jon Wilson’s 1920’s and 1930’s - a unique time in our history.

photography and digital art

Beautiful gardens, garden art and outdoor living spaces

The works and artistic visions of Ken Knieling.

Visual Arts from Canada & Around the World

Calatorind Descoperi

Captured moments of life as I see it

~ Telling the Truth, Mainly

Historian. Artist. Gunmaker.

Over 80,000 Miles Of the USA on a Moto Guzzi Breva 750.

All Pax. All Nude. All the Time.

Welcome to My World......

Poetry, story and real life. Once soldier, busnessman, grandfather and Poet.

Places to go and things to see by Gypsy Bev

Hiking with snark in the beautiful Pacific Northwest 2011 - 2013

光華商場筆電,手機,翻譯機,遊戲機...等3C產品包膜專門店

Welcome to my page!