Greenwich Village Sunday (1960 Documentary On The Counterculture / Beat

Culture In 1960’s New York)

http://youtu.be/nBfJyGjtxRg

Greenwich Village: what remains of New York’s beat generation haunts?

Inside Llewyn Davis

http://youtu.be/R3v9pcQJZRU

A new Coen brothers film celebrates Greenwich Village in its 60s heyday, but what’s left of Dylan and Kerouac’s New York? Karen McVeigh takes a cycle tour of the area

Inside Llewyn Davis still

A still from the Coen Brothers new film, Inside Llewyn Davis. Photograph: Alison Rosa/Studio Canal

Karen McVeigh

@karenmcveigh1

Sunday 22 December 2013 01.00 EST Last modified on Thursday 22 May 2014 06.51 EDT

Five decades have passed since America’s troubadours and beat poets flocked to Greenwich Village, filling its smoky late-night basement bars and coffee houses with folk songs and influencing some of the most recognisable musicians of the era.

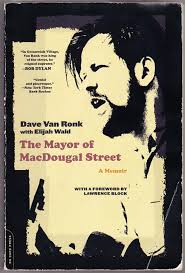

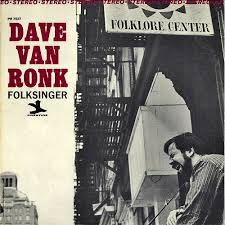

A few landmarks of those bygone bohemian days – most recently portrayed in the Coen brothers’ film Inside Llewyn Davis, out on 24 January – still exist. The inspiration for the movie’s fictional anti-hero, Davis, was Brooklyn-born Dave Van Ronk, a real- life blues and folk singer with no small talent, who worked with performers such as Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan, but remained rooted in the village until he died in 2002, declining to leave it for any length of time and refusing to fly for many years. Van Ronk’s posthumously published memoir, the Mayor of MacDougal Street, takes its name from the street that was home to the Gaslight Cafe, and other early 60s folk clubs.

The Village stretches from the Hudson River Park east as far as Broadway, and from West Houston Street in the south up to West 14th Street. Its small scale makes it easy to explore on foot and perfect for a musical pilgrimage, but the arrival last summer of New York’s bike-sharing scheme, Citibike, makes for a more adventurous experience.

CitiBikers in Greenwich Village

CitiBikers in Greenwich Village. Photograph: Alamy

I picked up a bike outside Franklin Street subway station, south of the Village in Tribeca, and headed out to the river, at Pier 45. Looking south you can see One World Trade Center: at 541m, it’s now the tallest building in the western hemisphere. Cycle or walk to the end of the boardwalk that juts out into the Hudson, facing Hoboken, New Jersey, and look to your left and you can see the Statue of Liberty. From there, it’s a short cycle along Christopher Street, up Hudson and along West 10th, to Bleecker Street, where designer boutiques such as Marc Jacobs, Michael Kors and Lulu Guinness mark the area’s steep gentrification.

On MacDougal Street, a jumble of comedy cellars, theatres and cheap eateries have mostly replaced the old, liquorless cafes and basement bars of the folk scene. It is the hub of New York University’s campus and many of the bars, falafel joints and pizza houses are priced for students, with $2 beers thrown in.

But several older venues still exist, including the Bitter End, which staged folk “hootenannies” every Tuesday and now calls itself New York’s oldest rock club”. The White Horse Tavern, built in 1880, still stands on the corner of Hudson Street and 11th. It was used by New York’s literary community in the 1950s – most notably Welsh bard Dylan Thomas. It was here, myth has it, that the writer had been drinking in November 1953, before he was rushed to hospital from his room at the Chelsea Hotel, and died a few days later.

Dave Van Ronk

Folk singer Dave Van Ronk, the inspiration for the Llewyn Davis character. Photograph: Kai Shuman/Getty Images

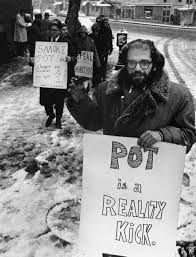

The original Cafe Wha? remains at 115 MacDougal Street, on the corner of Minetta Lane. In the bitter winter of 1961, when the Coen brothers movie is set, cash-strapped artists similar to Davis would take their chances at the open mic. It was here that Bob Dylan made his New York debut, and Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac performed. Cafe Wha? continued to attract artists and musicians long after the Village folk scene gave way to rock’n’roll. A notice on the door catalogues a few of the famous names who played here: Jimi Hendrix, Ritchie Havens, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard and the Velvet Underground. It is still a popular music venue, with a house band playing five nights a week.

The real centre of the folk scene back then, however, was Washington Square, where musicians would gather on Sundays to swap ideas, learn new material and play. According to folk singer and historian Elijah Wald, the ballad and blues singers who sat around the fountain in the park created sounds that would influence artists from Joni Mitchell and Joan Baez to folk-rock groups the Lovin’ Spoonful, the Byrds and the Mamas and the Papas. The hero of the Coens’ film is not Van Ronk, according to Wald, but he does sing some Van Ronk songs and shares his working-class background.

When I visited on a sunny but cold December day, there was only one musician, a saxophonist, playing under Washington Square’s stone arch, but at weekends the park fills with rap and jazz musicians playing to tourists and students. Bikes are not officially allowed inside the square, but there are Citibike stations around it, so it’s easy to park and walk around.

A block north of the park, on West 8th Street, is a historic 107-room property once known as Marlton House and home to many writers and poets, who were attracted by relatively cheap rates and the bohemian neighbourhood. Jack Kerouac wrote The Subterraneans and Tristessa while living here and, in a darker episode, Valerie Solanas was staying in room 214 in 1968, when she became infamous for stalking and then shooting Andy Warhol.

The Marlton Hotel

The new Marlton Hotel

Sean MacPherson, who owns the stylish Bowery and Jane hotels nearby, has just reopened the building as the Parisian-inspired Marlton Hotel (marltonhotel.com). I popped in to its very comfortable lobby for coffee and a flick through its copy of John Strausbaugh’s The Village: 400 years of Beats and Bohemians, Radicals and Rogues. And I caught up with Strausbaugh later, to ask him about the village in the early 1960s, when young idealists were living hand to mouth and sleeping on friends’ couches.

Advertisement

“In 1961, if you were in any way an artistic person in America, in that vast American landscape, you were a lonely figure,” said Strausbaugh. “You heard about San Francisco, you heard about Greenwich Village, and you went there. You didn’t play there to make money; you went there to be heard. Like Dylan, who played at the Cafe Wha?, then got another entry-level gig, then began playing at the biggest places.”

There were others, Strausbaugh said, like Van Ronk, who were talented, but whose ambitions were more modest than those of Dylan and Baez. The unique thing about the Village, he added, is that it survived so long as a bohemian enclave, from the early 1850s, when it attracted poets such as Walt Whitman, to the beatniks and folk revivalists of the 1950s and later.

“The left bank [in Paris] did not last 100 years, but the Village did,” he said.

Many of the buildings and sometimes entire streets in the Village have been preserved and are now home to some of the most expensive real estate in Manhattan and sought-after for their distinctive, old Greenwich Village look. A struggling folk artist might find a cheap meal in one of the student cafes around MacDougal Street, but they would never be able to afford to live in the area – or anywhere in Manhattan, realistically.

“It has not been completely finished off,” said Strausbaugh. “There are still a lot of theatres. But the people who make the music have not been able to live there for 20 or 30 years.”

Greenwich Village: Music That Defined a Generation Q&A at DOC NYC 2012

http://youtu.be/28cc8qaI748

Bleecker Street: Greenwich Village in the ’60s traces and tributes the bohemian Mecca’s part in the emergence of singer/songwriters and the folk revival during the ’60s. The initial passion and sense of discovery in this music remains undimmed, as politically and emotionally conscious songs by Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, Tom Paxton, Tim Buckley, Judy Collins, and Paul Simon are reinterpreted by contemporary artists like Chrissie Hynde, Ron Sexsmith, Beth Nielsen Chapman, and many others.

Track Listing

| Sample | Title/Composer | Performer | Time | Stream | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3:21 | ||||||

| 2 | 3:50 | ||||||

| 3 | 2:56 | ||||||

| 4 | 3:16 | ||||||

| 5 | 2:44 | ||||||

| 6 | 3:11 | ||||||

| 7 | 3:36 | ||||||

| 8 | 3:50 | ||||||

| 9 | 3:38 | ||||||

| 10 | 2:53 | ||||||

| 11 | 4:49 | ||||||

| 12 | 4:27 | ||||||

| 13 | 3:12 | ||||||

| 14 | 2:40 | ||||||

| 15 | 3:43 | ||||||

| 16 |