Hobo’s Meditation by JIMMIE RODGERS (1932)

DEDICATED TO DAVE CHRISTY

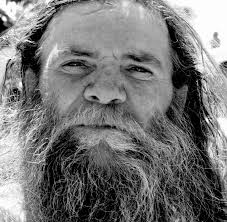

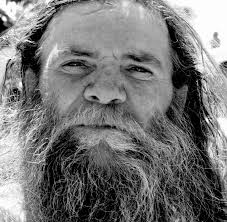

Hobo, 1894

Hard Times in America

In the period from 1893 to 1896 America suffered a severe economic meltdown that was surpassed in its tragic impact only by the Great Depression that followed four decades later. The causes were complex. They included a public panic to cash in paper currency for gold, a subsequent depletion in the country’s gold reserve and bankers calling in their loans to private industry as the value of the dollar continued to decline.

|

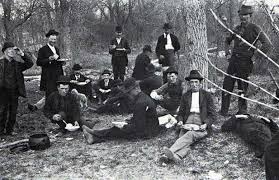

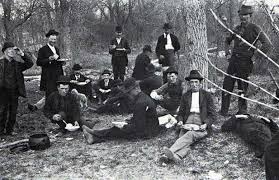

Members of Coxey’s Army on their way

to Washington, 1893 |

There was no government assistance. In Ohio, Jacob S. Coxey – owner of a failed business – decided to take matters into his own hands. In a move that foreshadowed the Bonus Army of 1932, he began a march on Washington in order to force the government to provide relief for the unemployed. As he made his way to the capital he was joined by what he proclaimed was an army of 100,000 destitute. However, when he entered the city he had a following of only 500. His plea fell on deaf ears as both the President and Congress refused to meet his demands. Coxey and his followers were subsequently arrested for trespassing.

The nation’s roads and railways were filled with the unemployed searching for a better life. They became hoboes, panhandling their way across the country in search of a job. Among them was eighteen-year-old Jack London, future author of Call of the Wild (1903).

London described his experiences as a hobo in a book entitled The Road. We join his story as he arrives in Niagara Falls, NY aboard a freight train. Walking into town in search of food, he runs afoul of the law:

‘What hotel are you stopping at?’ he queried.“The town was asleep when I entered it. As I came along the quiet street, I saw three men coming toward me along the sidewalk. They were walking abreast. Hoboes, I decided, like myself, who had got up early. In this surmise I was not quite correct. . . The men on each side were hoboes all right, but the man in the middle wasn’t. . . At some word from the man in the centre, all three halted, and he of the centre addressed me. He was a ‘fly-cop’ and the two hoboes were his prisoners.

He had me. I wasn’t stopping at any hotel, and, since I did not know the name of a hotel in the place, I could not claim residence in any of them. Also, I was up too early in the morning. Everything was against me.

‘I just arrived,’ I said.

‘Well, you turn around and walk in front of me, and not too far in front. There’s somebody wants to see you.’

I was ‘pinched.’ I knew who wanted to see me. With that ‘fly-cop’ and the two hoboes at my heels, and under the direction of the former, I led the way to the city jail. There we were searched and our names registered. I have forgotten, now, under which name I was registered.

From the office we were led to the ‘Hobo’ and locked in. The ‘Hobo’ is that part of a prison where the minor offenders are confined together in a large iron cage. Since hoboes constitute the principal division of the minor offenders, the aforesaid iron cage is called the Hobo. Here we met several hoboes who had already been pinched that morning, and every little while the door was unlocked and two or three more were thrust in on us. At last, when we totaled sixteen, we were led upstairs into the courtroom. . .

From the office we were led to the ‘Hobo’ and locked in. The ‘Hobo’ is that part of a prison where the minor offenders are confined together in a large iron cage. Since hoboes constitute the principal division of the minor offenders, the aforesaid iron cage is called the Hobo. Here we met several hoboes who had already been pinched that morning, and every little while the door was unlocked and two or three more were thrust in on us. At last, when we totaled sixteen, we were led upstairs into the courtroom. . .

In the court-room were the sixteen prisoners, the judge, and two bailiffs. The judge seemed to act as his own clerk. There were no witnesses. There were no citizens of Niagara Falls present to look on and see how justice was administered in their community. The judge glanced at the list of cases before him and called out a name. A hobo stood up. The judge glanced at a bailiff. ‘Vagrancy, your Honor,’ said the bailiff. ‘Thirty days,’ said his Honor. The hobo sat down, and the judge was calling another name and another hobo was rising to his feet.

The trial of that hobo had taken just about fifteen seconds. The trial of the next hobo came off with equal celerity. The bailiff said, ‘Vagrancy, your Honor,’ and his Honor said, ‘Thirty days.’ Thus it went like clockwork, fifteen seconds to a hobo and thirty days.

They are poor dumb cattle, I thought to myself. But wait till my turn comes; I’ll give his Honor a ‘spiel.’ Part way along in the performance, his Honor, moved by some whim, gave one of us an opportunity to speak. As chance would have it, this man was not a genuine hobo. He bore none of the ear- marks of the professional ‘stiff.’ Had he approached the rest of us, while waiting at a water-tank for a freight, we should have unhesitatingly classified him as a ‘gay-cat.’ Gay-cat is the synonym for tenderfoot in Hobo Land. This gay-cat was well along in years — somewhere around forty-five, I should judge. His shoulders were humped a trifle, and his face was seamed by weather-beat.

For many years, according to his story, he had driven team for some firm in (if I remember rightly) Lockport, New York. The firm had ceased to prosper, and finally, in the hard times of 1893, had gone out of business. He had been kept on to the last, though toward the last his work had been very irregular. He went on and explained at length his difficulties in getting work (when so many were out of work) during the succeeding months. In the end, deciding that he would find better opportunities for work on the Lakes, he had started for Buffalo. Of course he was ‘broke,’ and there he was. That was all.

‘Thirty days,’ said his Honor, and called another hobo’s name.

Said hobo got up. ‘Vagrancy, your Honor,’ said the bailiff, and his Honor said, ‘Thirty days.’ And so it went, fifteen seconds and thirty days to each hobo. The machine of justice was grinding smoothly. Most likely, considering how early it was in the morning, his Honor had not yet had his breakfast and was in a hurry.

But my American blood was up. Behind me were the many generations of my American ancestry. One of the kinds of liberty those ancestors of mine had fought and died for was the right of trial by jury. This was my heritage, stained sacred by their blood, and it devolved upon me to stand up for it. All right, I threatened to myself; just wait till he gets to me.

|

| Jack London |

When we had all been disposed of, thirty days to each stiff, his Honor, just as he was about to dismiss us, suddenly turned to the teamster from Lockport — the one man he had allowed to talk.

‘Why did you quit your job?’ his Honor asked.

Now the teamster had already explained how his job had quit him, and the question took him aback.

‘Your Honor,’ he began confusedly, ‘isn’t that a funny question to ask?’

‘Thirty days more for quitting your job,’ said his Honor, and the court was closed. That was the outcome. The teamster got sixty days all together, while the rest of us got thirty days.

References:

London, Jack, The Road (1907).

How To Cite This Article:

“Hobo 1894: Hard Times in America”, EyeWitness to History, http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com (2007).

BOXCAR WILLIE : Hank And The Hobo (train country song)

Death of the American Hobo (Documentary)

THE HOBO MUSEUM

Strangest Museums: Hobo Museum

Rachel Freundt

The Hobo Museum, Britt, IA

Housed in the former Chief Theater, the Hobo Museum celebrates the vagabond lifestyle, which happens to have a stringent code of ethics. It’s full of drifter memorabilia from the likes of Frisco Jack, Connecticut Slim, and Hard Rock Kid. Hobo crafts, art, photographs, and documentaries depicting the unorthodox way of life are also on display. It’s brought to you by the Hobo Foundation, which hosts an annual convention in town. hobo.com

What are Hobo Signs ?

Depression era symbols used by hoboes. In their travels for work, hoboes made marks with chalk, paint or coal on walls, sidewalks, fences and posts. The signs were meant to let others know what was ahead. (some call them the secrete language of the hoboes)

|

1. Good road to follow |

|

2. Religious talk will get you a free meal |

|

3. These people are rich (Silk hat and pile of gold) |

|

4. Camp here |

|

5. You may sleep in the hayloft here |

|

6. Warning: Barking Dog |

|

7. House is well-guarded |

|

8. This is not a safe place |

|

9. Good food available here, but you have to work for it |

|

10. If you are sick, they’ll care for you here |

|

11. This community is indifferent to a hobo’s presence |

|

12. Authorities are alert: Be careful |

|

13. Officer of the law lives here |

|

14. Courthouse, precinct station |

|

15. Jail |

|

16. Free telephone (Bird) |

|

17. Beware of four dogs |

|

18. No use going this direction |

|

19. Dangerous drinking water |

|

20. Doubtful |

|

21. A judge or magistrate lives here |

|

22. Here. This is the place |

|

23. A kind old lady (Cat) |

|

24. Hit the road! Quick! |

|

25. A beating awaits you here |

|

26. A trolley stop |

|

27. “Ok, alright” |

|

28. This way |

|

29. A gentleman lives here (Top Hat) |

|

30. Police frown on hobos here (Handcuffs) |

|

31. A man with a gun lives here |

|

32. There is nothing to be gained here |

|

33. The road is spoiled with other hobos and tramps |

|

34. Good place to catch a train |

|

35. Hold your tongue |

|

36. A crime has been committed here. Not a safe place for strangers |

|

37. Halt |

|

38. Dangerous neighborhood |

|

39. An ill-tempered man lives here |

|

40. Be prepared to defend yourself |

|

41. A doctor lives here. He won’t charge for his services |

|

42. Keep quiet (Warns of day sleepers, babies) |

|

43. The owner is in |

|

44. The owner is out |

|

45. There are thieves about |

|

46. A dishonest person lives here |

|

47. An easy mark, a sucker |

|

48. Good place for hand out |

|

49. There is alcohol in this town |

|

50. Fresh water and a safe campsite |

The hobo signs were copied out of a book called

“Hobo Signs by Stan Richards & Associates”

This is a rare example of tramp art in that I have found no references

in tramp art books to this wonderful pillow form. Its rarity is further

exemplified by the materials used: cloth, heavy carpet-like fabric and a

stuffing of sawdust. A great deal of time, skill and passion produced this

sturdy object. It has the classic pyramidic shape repeated with precision in

row after row of a deep red heavy fabric on the top. The edges where the top

meets the bottom are notched similar to tramp art woodcarvings. The bottom

exposes a smooth fabric that probably covers the entire object and displays a

light rust color. The dimensions are 9″ x 9″ square and 4.5″ high, in the

middle. The pillow weighs just under two pounds – 1lb. 15 oz.

The following is a beautiful example of bottle art

done by Carl Worner at some time in the early 1900s.

see more at http://sdjones.net/FolkArt/worner.html

The following are some examples of beautiful old

time wood carving. Notice the intricate detail and the skillful carving of the

balls in cages and chain links.

Next are some great carvings by our modern day

artist “The Tanner City Kid”. Note that the chain links are fully functioning

links as in a steel chain and the balls in the cages are loose movable objects

that are carved from the interior wood during the hollowing out process. I

think you’ll agree with me that Tanner’s work is as skillful as any of the old

timers.

From the office we were led to the ‘Hobo’ and locked in. The ‘Hobo’ is that part of a prison where the minor offenders are confined together in a large iron cage. Since hoboes constitute the principal division of the minor offenders, the aforesaid iron cage is called the Hobo. Here we met several hoboes who had already been pinched that morning, and every little while the door was unlocked and two or three more were thrust in on us. At last, when we totaled sixteen, we were led upstairs into the courtroom. . .

From the office we were led to the ‘Hobo’ and locked in. The ‘Hobo’ is that part of a prison where the minor offenders are confined together in a large iron cage. Since hoboes constitute the principal division of the minor offenders, the aforesaid iron cage is called the Hobo. Here we met several hoboes who had already been pinched that morning, and every little while the door was unlocked and two or three more were thrust in on us. At last, when we totaled sixteen, we were led upstairs into the courtroom. . .