|

In the winter of 1954-55 America was in an economic, social, and cultural interregnum. One style of life, one mood — like Victorianism or Edwardianism — was giving way to another. The industrial age based on the mechanical exploitation of coal and iron was giving way to electronics, computers, automation — with all the social and intellectual results such a basic revolution implies — but as yet few indeed understood what was happening.

The country was in a minor economic depression following the end of the Korean War. The Korean War represented a qualitative leap forward in technology and a lag in all other factors. However, morale broke down for a more simple reason. You can fight only one such war every twenty-five years. The Korean War took place within the effective memory of the Second World War. The academic and intellectual establishment, Left, Right, and Center, was shattered, demoralized, and discredited by the years of McCarthyism. Young men by the thousands were returning from the Korean War to the colleges disillusioned and contemptuous of their elders. They said to each other, “Keep your nose clean and don’t volunteer.” “Don’t believe anybody over thirty.” Communication between groups broke down. Only those of the older generation who had remained defiant were respected, listened to, questioned. Just as the Army took years to discover the almost total breakdown of morale in Korea, so the older intellectuals were unaware that a volcano was building up under them.

McCarthyism itself was an expression of breakdown of an older American synthesis. It has often been pointed out that McCarthy came from a small Wisconsin city, from a state which was once the home of the radical Progressive LaFollette, the most intransigent spokesman for the old agrarian Populism with its distrust of Wall Street, the New York and New England political and cultural establishment, isolationist, defiantly middle class. The doors were closed and locked forever for any escape into economic power of the Midwestern debtor society of small farmers, small-town independent merchants, and country bankers. McCarthyism is the last expression of what in central Europe was called the Green Revolution, devouring itself in impotence.

Most of the slogans of McCarthyism, like those of the John Birch Society today, had once possessed an entirely different meaning and had been formative ideas in the shaping of an older America. This content had been emptied out and replaced by truculent suspicion of any and all enlightened ideas which were forming the new, succeeding society. At the top America was in the hands of a sort of regency. The ship of state was steering itself. A generation was growing up which had known World War II only as children. Not one of the hopes or the promises of that war had been realized. Russia and the United States both had the Bomb and were striving to divide the world between them, to turn whole nations into aircraft carriers and army bases.

The Korean War had ended in a bloody stalemate and a wholesale breakdown of morale. While McCarthy was at the height of his power, with few exceptions the intellectual and moral leaders of America feared to challenge, if they did not actually support him. The entire academic community was shattered and terrorized both by McCarthy and dozens of local witch hunts and state-sponsored investigating committees. McCarthyism more than any other thing revealed to the young the moral bankruptcy of their elders. College professors complained that they were facing a silent generation who received their lectures with the response “no comment.” Nihilism in public life was reflected in nihilism amongst young intellectuals. The intellectual establishment, in fact, many of whom were ex-Communists, largely supported McCarthy. Nihilism in authority breeds nihilism in response, as it did in nineteenth-century Russia.

Although all the literary editors and the academicians were busy telling the world in the early fifties that the age of experiment and revolt was over, a very few critics, myself amongst them, had begun to point out that this slogan alone showed how complete was the breakdown of communications between the generations. Under the very eyes of the pre-war generation a new age of experiment and revolt far more drastic in its departures, far more absolute in its rejections, was already coming into being. The Beat writers were not at first part of this movement. Kerouac had published a very conventional novel, Ginsberg was writing dry whimsical little imitations of William Carlos Williams, Burroughs’s intoxicated lucubrations were not considered publishable even by himself. Gregory Corso, a naïve writer, a kind of natural-born Dadaist, was tolerated as an amusing mascot by the boys on The Harvard Advocate as a convenient practical joke.

San Francisco was the one community in the United States which had a regional literature and art at variance with the prevailing pattern. During the thirties it had become a strong trade-union town with a politically powerful Left, yet this radical activity was remarkably independent of the doctrinaire dictates of the American Communist Party. Perhaps the main reason for this was that most of the leadership had come from the IWW, the anarcho-syndicalist “One Big Union” movement which had been so strong on the Pacific Coast a generation before. During the war, work camps for conscientious objectors were established throughout the mountains and forests of California. These boys came down to San Francisco on their leaves. They met with San Francisco writers and artists who had been active in the Red Thirties but who had become, not professional anti-Bolsheviks, but anarchists and pacifists. During the war, meetings of pacifist and anarchist organizations continued to be well attended. Immediately on the war’s end a group of San Francisco writers and artists began an Anarchist Circle with public meetings which for five years were better attended than those of all the Socialist and Communist organizations put together. From this group and from the artists’ C.O. camp at Waldport, Oregon, came a large percentage of cultured activities in San Francisco which have lasted to the present time — a radio station, three little theaters, a succession of magazines, and a number of people who are considered the leading writers and artists of the community today. And it was this sympathetic environment that the so-called Beat writers discovered around the early fifties.

There is probably more misunderstanding and misinformation current about the Beat Generation than any other phenomenon in contemporary culture. This is due to the fact that the sensational press were quick to seize on the Beat writers and to reconstruct them in their own image. The public personality which had been grafted onto Allen Ginsberg is the kind of person the editors of Timemagazine would be if they only had the nerve. The Beat writer is what the French call a hallucination publicitaire, Madison Avenue’s idea of a Revolutionary Bohemian Artist. It bears almost no relation to actuality although the delusion, the false image, is a continuous temptation to the real writers. They can always find applause and profit by living up to the delusions of their enemies.

The factual historical misinformation about the Beat Movement is immense. In the first place, there never really was a Beat Movement, with the exception of four writers — Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, and Gregory Corso. Second, these writers have had little connection with San Francisco down the years and they were all fairly well known amongst bohemian intellectuals before they ever saw the city. William Burroughs, several years older than the rest, had first brought them together in New York shortly after 1950. Kerouac and Ginsberg were at that time students at Columbia and Gregory Corso a non-student at Harvard University. For several years a group of very hip young men had been running a magazine in St. Louis called Neurotica. About 1952 two of the editors, Jay and Fred Landesman, moved to New York and opened a large loft studio a block away from the San Remo Café, then the most in or the most far out of the Greenwich Village bohemian hangouts. It was at the Landesmans’ studio that Kerouac, Ginsberg, Corso, and Burroughs first made contact with the literary bohemian society of New York. There are several novels about this phase of the movement. With the exception of Clellan Holmes’s Go, they very significantly do not concentrate on the specific behavior patterns peculiar to the four Beats but describe the general scene in the first postwar generation of disaffiliation, revolt, disgust.

The trouble with the New York scene around the San Remo Café was its total mindlessness. There was nothing there but disgust. When Ginsberg and Kerouac began visiting San Francisco in the course of their student wanderings around the country during vacation the effect on them was explosive. In 1956 I asked the proprietors of the Six Gallery, one of the launching pads of abstract expressionism, if they would sponsor a reading by Walter Lowenfels, who could not get a hall anywhere in San Francisco because he was under indictment for violation of the Smith Act. He was an editor of the Philadelphia edition of The Daily Worker and had been a well-known modernist poet in the Paris America of the late twenties and early thirties. (He is the Jabberwohl Kronstadt in Henry Miller’s Black Spring.) The proprietors of the gallery were delighted at the chance to defy authority. Nobody under 40 had ever heard of Lowenfels as a poet but to everyone’s amazement the large gallery was jam-packed with young people who came to hear him read. The proprietors were so delighted that they asked me to arrange other readings. The next one made history. It was a parade of the city’s leading avant-garde poets — Robert Duncan, Brother Antoninus, Philip Lamantia, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Michael McClure, and four young men who had just come to town — Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, Gregory Corso, Allen Ginsberg. Here Ginsberg first read Howl, which he had been working on in a state of excited entrancement for the past two weeks. The effect beggars description. A new folklore and a new folkloristic relationship between audience and poet had been created.

The Six Gallery reading is usually said to have launched the Beat movement. In fact the only connection is Allen Ginsberg himself. Kerouac was present but did not participate except to create periodic disturbances. Public reading of poetry had become a regular institution in San Francisco as early as 1928 and was a principal attraction in the John Reed Club, the Communist artist and writers’ organization, and in the Jack London Club, the competing Socialist group. Poetry readings were given by the united pacifist Randolph Bourne Council and later by the San Francisco Anarchist Circle all through the war and the decade after, mostly in the Arbeiter Ring, the largely Jewish workingmen’s fraternal organization. The San Francisco Poetry Center had been in existence for some years and had already moved to San Francisco State College. The annual Poetry Festivals had begun shortly after the war and the satirical musical review, The Poets’ Follies, under the direction of Weldon Kees and Michael Grieg, with acts like the beautiful stripper Lili St. Cyr reading T.S. Eliot’s Ash Wednesday (dressed), had already shown three consecutive years. Kenneth Patchen, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and myself had already started reading poetry to jazz in local jazz clubs. (The great bassist and composer Charles Mingus was closely associated with many of the artists and writers of San Francisco during the war years.)

The older poets had all been active in the anarchist and pacifist movement for many years, had been conscientious objectors during the war, and worked in C.O. camps or in hospitals. Of the younger, Philip Whalen and Gary Snyder had grown up in IWW circles in Oregon and Washington.

It was from this background that the very superficial and largely factitious interest in Zen Buddhism shared by Kerouac and Ginsberg comes, not, as is often imagined, from contact with G.I.’s returning from China, Japan, and Korea. The influence of Oriental religion on San Francisco is partly indigenous. There are many large, flourishing Buddhist churches in the Bay Area with mostly Japanese congregations, but with Caucasians as well, and with many contacts with the general community. I know of only one returned G.I. who came back with an interest in Buddhism. He had no contact with the San Francisco intellectual community except myself and became an academic Buddhologist. On the other hand, Alan Watts, Gerald Heard, Christopher Isherwood, Aldous Huxley, and myself in California and the painters Mark Tobey and Morris Graves in Seattle were centers of interest in Oriental religion, but more especially in the revival of the contemplative life, all through the war years. Most of us conducted seminars, discussion groups, and retreats teaching younger people the elements and the techniques of nonviolence and meditation. These activities of course still go on in different forms and on a much larger scale. Gary Snyder is an ordained Zen monk and learned in the poetry and religious literature of India, China, and Japan. I will always remember the night Jack Kerouac appeared uninvited at my home, sat down with a jug of cheap port wine beside him on the floor, announced that he was a Zen Buddhist, and discovered that everybody in the room read at least one Oriental language.

Kerouac’s portrayal of this aspect of San Francisco culture, in The Dharma Bums, would be a malevolent libel if it were deliberate. It is only an expression of his own baffled ignorance in the face of human motivations and beliefs, which he was intrinsically incapable of understanding. It is this ignorant confabulation presenting itself as reality which accounts for the almost complete eclipse of Kerouac’s reputation. Young people no longer read him and consider him absurd, the apotheosis of uptight. It is not just the misrepresentation of fact but the misunderstanding of motivation, the distortion of character and the ignorance of the ideas involved which has caused him to be no longer read by people who really understand what he is talking about. The world view of post-modern culture and of the San Francisco version of it especially has now become the common possession of millions of young people and it is backed up with a whole literature and way of life which bears no real resemblance to the disorderly conduct for its own sake of Kerouac’s characters.

Another influence on the San Francisco scene was Henry Miller, who had lived in Big Sur since 1941 and who was known to most of the San Francisco writers. I doubt if either Ginsberg or Kerouac ever read much of what he has written. They once hitchhiked down the coast 130 miles to visit him and were not admitted. Miller’s very positive and powerful religious convictions and love of life have little to do with the nihilism of the beatnik.

I should mention by the way that the word “beatnik” was invented by the San Francisco columnist, Herb Caen. The term “beat” was a common slang phrase amongst bop musicians and often, like “funky,” and other bop slang, was used in a reverse sense, but usually to mean emotionally exhausted. The term “Beat Generation” was first used simultaneously by Clellan Holmes, in an article in the New York Times Magazine, and by myself in New World Writing. This article and others like it which I wrote at the time about the then youngest generation of poets — the new age of experiment and revolt — included along with Ginsberg and Corso, Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Denise Levertov, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Robert Duncan, Brother Antoninus, and many others. This was an unfortunate linkage which has endured to this day. None of these people has anything to do with any imagined Beat movement. Their writing is of the widest variety and they share only a rejection of the morals of a commercial civilization and a return to the international idiom of modern verse which had been stifled in America by the Reactionary Generation of the forties and the Proletarians of the thirties.

William Carlos Williams and Ezra Pound, but Williams especially, were strong influences on this entire group, as were the unreconstructed modernists surviving from the inter bellum years — Louis Zukofsky, Walter Lowenfels, Sam Beckett, Kenneth Patchen, and myself. Another factor in San Francisco culture that is very important is its closer connection with London and Paris than with New York. San Francisco intellectuals first made contact with London anarchists during the Spanish War and all during the Second World War correspondence was kept up with people like Sir Herbert Read, Alex Comfort, George Woodcock, Charles Wrey Gardner, Tambimuttu, and others. I for instance first read the poetry of Denise Levertov when she was a Land Girl in Essex and introduced her by mail to Charles Wrey Gardner, who was publishing Poetry Quarterly in Billericay. George Barker lived in Big Sur in the forties. Dylan Thomas spent two long periods in San Francisco.

French publications of the résistance like Éditions de minuit and Pierre Seghers’s Poésie arrived in G.I. mail in some quantity as soon as the Americans got to Africa, and lesser amounts had trickled in from the very beginning. Writers like Simone Weil, Sartre, Camus, and poets of the résistance like Char, Frénaud, Rousselot, Seghers, Follain, Guillevic, were read in San Francisco before anyone in New York literary circles had so much as heard of them. People in San Francisco had corresponded with Simone Weil from the days of the Spanish War.

All this goes to make up the picture of the emergence of the post-modern worldwide intellectual culture in which the Beat Generation was only a minor episode, a kind of misunderstanding on the part of a few intellectual amateurs and following them the literary journalists of the gutter press. The present revolt of youth, the new radicalism, the democratization of the avant-garde, are all aspects of a worldwide revolution in the very foundations of culture, basic changes in ways of living, the emergence of a fundamentally new civilization. Allen Ginsberg has survived into this new civilization, and is today one of its leading figures in Tel Aviv, Calcutta, Moscow, but the Beat Generation placard which was hung around his neck has long since dropped away. Only squares and elderly Communist bureaucrats in the minor Balkan countries used the term “beatnik” after 1960.

What was the significance of the Beat movement, so called? What was its effect on the evolution of American literature and culture? It was the form in which the mass disaffiliation of postwar youth from a commercial, predatory, and murderous society first came to the attention of that society itself. Kerouac’s On the Road was a bestseller. It served the purpose of detective stories and cowboy romances and girlie magazines for the vast new white-collar class; the grey flannel suburbia escaped into a dream world of fast cars, easy women, drunken parties. This world of Jack Kerouac’s had essentially the same values as did the world of the upwardly mobile new professions. A whole literature of dope, homosexual prostitution, knife fights, sado-masochism, gang bangs has followed in its train — the soap operas and horse operas of the lumpen petty power élite, the little Jet or Squirt Set, in the decade since its publication. Their life has gradually come to resemble their escape literature. The effect of Kerouac on young people, on the revolt of youth, on the genuinely disaffiliated, was minimal. True, all sorts of juvenile delinquents abandoned their disorderly conduct in the soda fountains near the high schools of Cle Elum, Fort Dodge, and Tucumcari, hitchhiked to San Francisco, and started making like Kerouac’s characters in North Beach. But this invasion vanished like the Gauls from Rome. It was unable to hold the territory. While it lasted it had certain characteristics that distinguished it from the older bohemia or the present worldwide culture of secession. It was life-denying. It hated sex. It used alcohol only for oblivion. One of the diagnostic signs of the Beat syndrome, very obvious in Kerouac’s and Burroughs’s books, was contempt for women. The Beat come-on was to treat a girl exactly as one would treat a casual homosexual pickup in a public convenience. An interesting thing about the winter of 1957 in North Beach was the wave of young girl suicides, one of them the mistress of the hero of On the Road. Another man had killed his wife in Mexico some years before, playing William Tell at a party. This kind of senseless nihilism was pushed aside by the rising tide of genuine revolt with a new ethic and a new kind of social responsibility and a new and very male and very female sexuality — even though the squares are still bothered because everybody wears long hair.

Burroughs is a special case. His work is source material for social history, not literature, and as such of minor importance. He is also one of many writers mining a current faddism. Corso is another special case. Like most naïves, he really has little relationship to literary literature. It is possible to relate le douanier Rousseau to the beginnings of Cubism but the relationship is fortuitous. If anything, they were influenced by him, certainly not the other way around. He wanted to paint as photographically as possible. This does not mean that Corso is not a considerable poet; he is, just as Rousseau is a very great painter.

Of the four Beat writers, Ginsberg is much the most important. Howl has sold hundreds of thousands of copies and been translated into most civilized languages and many semi-civilized ones. It is a true vatic utterance, the speech of a nabi, an excited Hebrew prophet, and the closest parallels in literature are Hosea and Jeremiah. For several years it was fantastically popular with American students and played an important role in reinforcing and consolidating their contempt for the conspiracy of the Social Lie — the American Way of Life. Ginsberg has none of the life hatred, nihilism, praise for oblivion, sexual disgust, or social destructiveness of Kerouac and Burroughs. He has never lost a certain boyish ingenuousness which leads him to showing off on television and provoking arguments about dope and homosexuality with Bolshevik bureaucrats. In some ways he resembles, most especially in his unquenchable youthfulness, Colin Wilson. The great difference between the Angries and the Beats is that the Americans rejected the entire social structure. They didn’t want to be admitted to the old Establishment or to found a new one. They wanted to pull down all Establishments whatsoever. More important even than this — all of them, even Kerouac and Burroughs, were interested in what the avant-garde between the wars called The Revolution of the Word. They were interested in attacking, disorganizing, and in the case of Ginsberg and Corso, reorganizing the structure of the human sensibility as such through a revolutionary use of language, the overturning of the old patterns of logic and syntax. This last phrase is almost exactly that of the surrealist theoretician André Breton and it is still believed in passionately by the Beat poets. On the other hand, I have found in interviews with the leading Angries that when you question them about this matter they are unable to understand what you are talking about — it’s some French thing, like eating frogs and snails. An American television interviewer, after a long hassle trying to get the most articulate of the Angries to understand what he was talking about, gave up with the remark, aired throughout the world, “I guess I’d be angry too if I went to all that trouble and ended up writing like bum Galsworthy.” Whatever the faults of the Beats, they were the first challenge to what we call the basic values of the civilization to reach a popular audience, but it must be remembered that they were essentially a small focal point in an overwhelming social movement, a highly visible ripple in a worldwide New Wave.

II

The most significant, if not the best by older critical standards, literature in America today is to be found, not in books, or even in the established literary magazines, but in poetry readings, in mimeographed broadsides, in lyrics for rock groups, in protest songs — in direct audience relationships of the sort that prevailed at the very beginnings of literature. The art of reading and writing could vanish from memory in a night and it would not make a great difference to the poetry, or even much of the prose, of the youngest generation of poets and hearers of poetry. This is the new world of youth which so disturbs the oldies. Rightly so, it is a world they never made. In it they are strangers and afraid — totally unable, most of them, to comprehend what is happening.

The last few years have seen a steady stream of American books on the New Left, on the revolt of youth, and especially on such mass phenomena as the Free Speech Movement in Berkeley and the anti-Vietnam protests on all the campuses. With no exceptions these books have been written by ideologues, men of the Thirties, or by somewhat younger people who grew up in lingering Marxist sectarian groups. They all try to assimilate a non-ideological, non-political worldwide movement to the programmatic delusions of another age.

What we are witnessing today is a profound change in the patterns of life and an even greater change in its possibilities. This affects all nations — I used to say except Red China — beatniks, hooligans, gammlers, stilyagi, provos, hippies — they’re not just to be found in Amsterdam, in the East Village in New York, on Haight Street in San Francisco, or on Notting Hill in London. Terms of abuse only represent the attempt of the squares and the oldies to exorcise behavior which they do not understand with stereotyped formulas which they think they do.

Britain is a special case. British society assimilates all things — the ceremonies of the monarchy, the country house orgies of high life, the stodgy Communist Party of Great Britain. Today the Teddy Boys are middle-aged; the Angries lunch in the Reform Club; and even Mods and Rockers, no longer young, have been digested by a homogeneous and homogenizing society. Carnaby Street is already part of the Establishment and a tourist attraction second only to the boys in bearskin busbies. The subculture of secession in Great Britain is a kind of Fabian anarchism, slowly penetrating all structures of the society by metastasis. This is not true anywhere else and it makes the profound and ever-widening schism in the soul in modern society difficult to explain to a British audience. Can you imagine an American president making the very influential American anarchist, critic, poet, psychiatrist, urbanist, educator, Paul Goodman, a knight like Sir Herbert Read, or Bob Dylan an M.B.E. like John Lennon?

Most nations show no capacity to absorb their youth culture. Not only does the sight of the long coiffure give most premiers, ministers, and cabinet secretaries running and barking fits, but it is becoming increasingly difficult for young people in the uniform of secession — beards, long hair, blue jeans — to cross national boundaries. They are harassed with elaborate customs inspections and forced to give proof of their solvency and in some countries, Greece, Morocco, and Algiers for instance, are refused entrance on their appearance alone. Les douaniers are perfectly right; they are the enemy. If there were enough of them national boundaries would disappear instantly.

Does this mean that they are Internationalists and Pacifists, capital I and capital P? Certainly not. Any question like this provokes a false answer. What is happening cannot be explained in terms of ideology. Ideologies are at best schematizations of social reality, never fit the facts, and wear out rapidly like ill-fitting shoes. Suppose Hitler had conquered the world and had totally suppressed all the documents and the very memory of the writings of Marx. Would the industrial process then have failed to produce “human self-alienation”? Would there no longer be any necessity for the capitalist system to expand regardless of human values or else collapse? Would the ratio of labor power to capital investment and with it the rate of profit stop falling? Would the failure of the economic system to ensure a minimum of life satisfactions for the majority of its members not have resulted in an ever-increasing demand for a fundamental change in the quality of life? Do all these things depend upon familiarity with a four-foot shelf of books full of errors and failed prophecies? Revolutionary consciousness is not the product of courses in the ABC of Marxism. It is a kind of natural secretion of the hopeless contradictions of modern society and it is most doubtful if Marx would have recognized it — in fact he notoriously was as intolerant as any country pastor in Ibsen of the mild bohemianism of his own children.

Fortunately for the present generation, the hundred years from 1848 to 1948 witnessed the total bankruptcy of all ideologies. The revolutions of the past, said Teilhard de Chardin, had economic and political objectives, but the latter half of the twentieth century will see a worldwide revolutionary struggle to change the quality and meaning of life. This revolution cannot be understood unless we realize that it starts off with the slate wiped clean. There is no worse guide conceivable than an aged ex-Left-Trotskyite holding down a professorship in a multiversity, the boss of a corps of graduate students tagging demonstrators about the campus with questionnaires.

Today there is growing up throughout the world an entirely new pattern of life. For several years I have called it the subculture of secession but this it is no more — it is a competing civilization, “a new society within the shell of the old.” It has come about not through books or programs but through a change in the methods of production. It is a society of people who have simply walked into a computerized, transistorized, automated world, a post-industrial or post-capitalist economy, in which there is an ever-increasing democratization of at least the possibilities for a creative response to life.

What does democratization of the arts mean in practice in America? What happens when an entire subculture takes to poetry, rock groups, folk songs, junk sculpture, collage pop pictures, total sexual freedom, and costumes invented ad lib? What is the relationship of this literary and artistic activity in which everyone can take part to the official, professionalized culture? What is the relationship of the Establishment and the Secession? Obviously the younger people are both seceding from something and acceding to something. What?

Conventional academic poetry is certainly flourishing in America. Most poets of this type, in fact all of them, have very good jobs in universities which pay from $8000 to $30,000 a year. Their books do not sell, but readings on the poetry circuits of the Establishment are at least as profitable as ever was Vaudeville. Any established poet can ask and receive fees from $500 to $1000 an appearance, thus nuzzling the heels of concert stars on the rung above him.

There is another world of poetry readings altogether. Ferlinghetti, Ginsberg, and Bob Dylan form the only bridge from one world to another. I have no idea what Bob Dylan’s sales are, but Ferlinghetti’s Coney Island of the Mind alone had sold 250,000 copies by 1969. The book sells at the rate of 45,000 a year and has been translated into Swedish, Danish, Polish, Russian, French, Italian, German, Spanish, Czech, Slovak, Serbian, at least, not counting pirated editions in the Orient and in the smaller Iron Curtain countries. Ferlinghetti’s other books sell 20,000 a year, altogether. Ginsberg’s Howl has sold over 200,000 in the U.S. alone.Kaddish had sold 30,000. Reality Sandwiches, 20,000. The foreign editions of Ginsberg are innumerable. Dylan Thomas’s sales are still about equal to Ginsberg’s or Ferlinghetti’s and he was one of the most popular “platform personalities” in American history — but not in Great Britain!

People like Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and the leading rock groups have fabulous incomes. Yet even those who have gone over to the nightclub circuit like Peter, Paul, and Mary and Judy Collins still live essentially the same lives as the seceders on unemployment payments or welfare, with the same values and the same pleasures, and they are even more active in civil-rights and civil-liberties struggles. That is the point — in a society of abundance where the poor live better than Charlemagne, everybody can afford to be ethical. Aristotle confines his Nichomachean Ethics to the moral behavior of free citizens of Greek city states. Slaves, says he, cannot afford ethics — their wills are not their own. The reason for the vast eruption of moral protest in America since the beginning of the civil-rights struggle is that people now can afford to be good — aggressively so. Nothing serious, except possibly murder, can happen to a young girl who leaves a Northern college and goes to the South to help out. Suppose her parents disown her? She won’t starve. She’ll have an interesting life and be welcomed back to school with a scholarship. In an abundant society a large number of people will discover that ethics is (or are) fun — like poetry or jazz or happenings. Only in a wealthy society could the film play so important a role. Kenneth Anger, Stan Brakhage, Bruce Conner, James Broughton, one of their films costs more than James Joyce made on Ulysses — yet these film-makers are as much a part of the scene as Gary Snyder, whose life motto is, “Don’t own anything you wouldn’t leave out in the rain” — or as Joan Baez, who must make as much as Maria Callas.

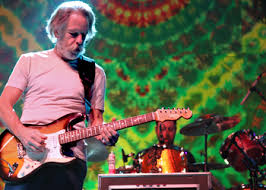

Far more important than their large sales, readings by Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti, Gary Snyder are mass demonstrations where the charisma practically reeks, and could be bottled and sold. In the new subculture, no longer very submerged, these poets have founded a way of life. In countless coffee shops and community pads people gather nightly, play records of rock groups like The Jefferson Airplane, The Grateful Dead, The Only Alternative and the Other Possibilities, records of protest and of folk singers like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, or records of the modern jazz musicians, Ornette Coleman, John Handy, Cecil Taylor, Archie Shepp; or they may beat congas and atonal guitars polyrhythmically and recite their own poetry. Usually this poetry has no life beyond the immediate occasion. Sometimes small groups, essentially neighborhood communities, in the analogs of New York’s East Village and San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district, which are springing up all over the country, get together and put out duplicated publications of their own poems. Sometimes they even manage a hand press, and produce a regular magazine. The girls set type, the fellows turn the cranks, babies crawl on the floor, and cats tip over the fonts and piss in the pied type. The first magazine of this kind from such a group was The Ark, published just after World War II by the San Francisco Anarchist Circle. Since 1946 its progeny are numbered in thousands, but they still come from the same kind of group (although nobody is so square as to call himself an anarchist anymore), and are produced in the same circumstances in the same cold water flats with rubbish décor.

Like the old French Canadian threat of winning the battle of the cradle, this is a revolution which hopes to win simply by outliving and outbreeding the squares. In a few years most people will be under 25. In this world there are no economic problems. This is the world of post-Theobald man, functioning on the bare minimum subsistence income which the modern Welfare State actually does guarantee right now. These people not only accept their redundancy, they glory in it. Nobody works any more than enough to get his unemployment insurance. The standard of living is exactly that of the unsophisticated redundants — two pairs of blue jeans a year in Appalachian fashion, welfare cuisine of lots of rice and beans, wine at $1.30 a gallon, and grass consumed till every roach has vanished from its crutch. Where the records and books come from, I don’t know. I guess they’re stolen. Paintings, and found art, like the poetry, are authentic products of cottage industry.

If you democratize art you necessarily, at least at first, lower its standards. Anybody can do junk sculpture or drip painting or collages. Anybody can sing as well as Bob Dylan. Anybody can write as well as most of the poems given away in San Francisco shops by the Free Poetry Movement (on the butcher’s counter a stack of mimeographed sheets and a card, “Free Poems — Take One”). When Lenin said the time would come when any cook could run the State he didn’t say he’d be a very good cook or a very good governor. However, already a new set of artistic and literary values or criteria are emerging. They reflect the interpersonal relationships and their attendant values of a quite different kind of society — anti-predatory, anti-exploitative, personally, morally engaged. This results in a quite different formal esthetic — and through all the apparent chaos, a new concept of form can be seen emerging and new evaluations. Fifty years of socialist power have not ended human self-alienation but seem to have increased it. You can’t expect the Free Poetry Movement to produce Homers overnight or even T.S. Eliots. However — the Seceders have attacked precisely alienation and I suppose that is the fundamental criterion: does this poem or song or story or film or painting or play overcome the gulf between man and man and between man and himself — even a very little?

This is a revolutionary movement which has substituted for “Workers of the World Unite — You Have Nothing to Lose But Your Chains,” “Please Let Me Alone, Man; I Just Want to Do Nice Things With My Friends.” Innocuous as this might seem as a revolutionary slogan, it is a specter that is haunting Europe, and America, and Asia as well. In Prague there was a coffee shop called “The Viola” where Ferlinghetti was recited to records by Thelonious Monk, although in Prague in cette belle époque between the wars nobody ever thought to recite Allen Tate to Stephen Foster on the banjo.

Poetry, probably because it is the one art most difficult to turn into a commodity, is, with folk-rock and jazz, the focus of life in this world. An equally important reason is that contemporary disaffiliation is essentially a religious challenge to the universal hypocrisy of the Social Lie, and poetry, of all the arts, can give most specific, most overt, most challenging expression to religious values. Beginning with Howl, which is a poem by a nabi of the New York Subway, strictly in Allen Ginsberg’s own tradition, that of the Hebrew prophets, most of the poetry of the subculture of secession has been religious and its practitioners have been devoted to the theological virtues — voluntary poverty, sexual honesty, and obedience to personal integrity.

In such a culture, particularly if it is floated by, rather than submerged in, an affluent society like our own, economic questions wither away, more rapidly than in Lenin’s State. The significant poetry of the youngest generation escapes altogether from the strictures of the dismal science. These are the people who have walked into the Great Society uninvited, without even turning down an invitation to the White House. They have taken possession of the social results of the cybernetic future.

Political organizations that represent one pole or the other of the vast evil try to use this subculture without success. Turnouts like the great Vietnam protests are not organized by the Progressive Labor Party or the Students for a Democratic Society or any of the other tiny neo-Bolshevik groups that crowd their way into the TV cameras. They crank out leaflets and go through the mechanical patterns of “leading the struggle” but they are very minor external parasites on the tail of a vast mass movement. When they take over and force their people to the front, they find themselves without followers. The youth of America — or the rest of the world for that matter — do not protest the Vietnam War for geopolitical reasons, in the interests of Chairman Mao or Ho Chi Minh or the Kremlin — but as a murderous conspiracy of the aged, and for purely human and moral reasons. They look on the war as a war of the old men at the desks and on the podiums against the young men and women in the rice paddies and behind the guns. When political groups try to force this protest into their own channels they discover that the protestors have suddenly gone away. The crazier violent groups are doubtless, as always, 75 percent agents provocateurs.

There is a good deal of confusion about several quite different types of youth behavior. Just because conduct is revolting, that doesn’t mean it is revolt. There is no more relationship between the wild boys of the road — motorcycle clubs like Hell’s Angels or some of the more violent Rocker types — and poets like Gary Snyder or singers like Bob Dylan or Joan Baez, than there is between an Establishment writer like John Osborne and people who hunt foxes. A good part of what goes on amongst people under thirty is simply the perennial youth culture we have always had, which has always disturbed the old, from Babylon to Benny Goodman. Today the opportunities for mischief offered by affluent society simply make it all that more conspicuous.

When the Hell’s Angels announced they were going to disrupt the Vietnam protest march in Berkeley, Ken Kesey and Allen Ginsberg invited the leaders down to Kesey’s mountain home and turned them on with LSD and the next day they were as meek as lambs, loved all sentient creatures, and rode in the march on Kesey’s Op-Art truck. That’s the connection.

Which brings up the subject of narcotics. It is true that more young people smoke marijuana than drink alcohol (except for wine and beer). They say it is obviously less harmful, and less harmful than tobacco. Most medical opinion agrees with them. The reason for the persecution by the State is that marijuana is impossible to tax. Anybody can grow it in a window box in a moderately dry and warm climate. But by very definition, a pleasure which is not taxable is a vice.

As for LSD and the various hallucinogens and stimulants (speed) — the more dangerous ones are losing their popularity. People who use LSD claim that it doesn’t cause lung cancer or lead men to beat their wives or women to let their children starve. Since older Americans smoke two to four packs of lethal cigarettes a day and consume immense quantities of alcohol — solely to get drunk — and go to sleep with the goof ball and get up with a pep pill — their moral horror when they discover their children smoke grass or drop acid is a little disgusting. I have been in some pretty low pads but I have never been in one whose atmosphere of evil and debauchery approached by miles that of an ordinary financial district junior executives’ and stenographers’ cocktail bar.

Total sexual freedom — astonishingly enough to the elders — doesn’t seem to make a great deal of difference. There is total sexual freedom in the Wall Street or Madison Avenue cocktail lounge too — but there it is motivated by malevolent mutual hostility and exploitation. In the typical post-Beat cooperative rooming house it is usually motivated by a rather excessively aggressive mutual affection, a vulgarized hobo Buddhism. An older-type square is liable to turn off abruptly when the young lady poet says as she takes him to bed, “I just love all sentient creatures, don’t you, hunh?” Most remarkable is the sharp decline in homosexuality in a completely permissive environment.

Again, the Carnaby Street costume is often confused with the Revolt of Youth. This is absurd. Carnaby Street is for the rich — rich by the standards of the secession. It is a remarkably successful attempt of London to disrupt and capture some of the international fashion trade so long held by Paris and then by Italy and New York. (The Beatles and Carnaby Street are what defunct empires produce, attempting to rectify the balance of payments when everybody can make their own steel.) Nor is it really peculiarly British. Clothes like this are common now everywhere amongst the junior Jet or Squirt Set. Portobello Road and Waterlooplein costumes — Edwardian evening gowns topped by 1840 army dress tunics, or togas, or chitons worn with high button boots are something else. This fashion for optional dress — dress any way you want — began in San Francisco and New York about 1960. Before that it had been confined to a small handful of post-Beat intellectuals and their girls, mostly in San Francisco — but with a few friends in the East Village. Now it is also worldwide but I think it is more than a fashion — it is here to stay. In the future probably both rich and poor will dress any way they like. The society can produce an unlimited variety of costume. Clothes are certainly not crucial — but it is beards, long hair, bare feet, that seem to distress the oldies more than even dope and promiscuity.

What lies back of all this confusion is simply that the older generation believes that those who reject their values must be delinquents. They are incapable of seeing that a new culture with a new system of values has sprung up around them. People ask loaded questions like: Do they sponge on their parents for a college education? No. In the American West a college education costs so little it can be earned by part-time work. Many students attend classes without registering or paying anything and the hipper teachers wink at them. I conducted a seminar last year in which half the students, and by far the better half, were so-called non-students.

Do they loaf and write poetry on welfare or unemployment payments — in other words on the taxpayers’ money? What’s wrong with that? Better write poetry with the taxes than what any current administration is doing with them. One bomber destroyed while attacking a bamboo bridge or burning up babies costs more than it would cost to keep all the poets in America for a year.

Such questions are invidious and show a complete lack of understanding of people whose only response is, “Go away man, I just want to do nice things. I love everybody. Something is happening and you’ll never know what it is.”

What are the things the seceders accede to? Where and how are they engagé? In issues that directly effect the quality of life. The provos of Amsterdam are no different than the people in the East Village or San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury. They are against and will act in mass against the destruction of the environment by the automobile, the pollution of the atmosphere and waters, the censorship of art, drama, literature, they will act for all civil-rights and civil-liberties issues. They will even support trade-union action to organize the wage slaves in California agriculture — because this is a moral issue. Otherwise they are antagonistic to trade unions as part of a vicious system. They will fight for free theater and music in the parks. For neighborhood cultural centers — and of course in attacks by the Establishment on the Blacks — they appear in force.

The society is vulnerable to this kind of direct, personal spontaneous attack. If you put your hand in an old-fashioned gear box of a steam shovel, you will get it torn off. If you poke your finger into a million-dollar computer, it will shudder, choke, and break down. Four Negro boys walked into a cheap Southern restaurant and asked for hamburgers and sat and waited quietly — that was more than a decade ago. They began a process which nothing now can ever stop.

Similarly, poets and singers and even underground moviemakers are — each one — more subversive of the old society than any organization or party possibly could be anymore. And they have their own international. The London Scene is top-heavy with Americans — especially San Franciscans. Provos seem to go back and forth across the Channel every week. The Underground Press Syndicate includes not only The Berkeley Barb and The East Village Other, but the London International Times, and Peace News, and papers in Amsterdam, Stockholm, Paris, and the Rhineland. Although they are many times as many, like the old Paris-London-America avant-garde around the Café Dôme in the twenties, everybody seems to know everybody else — and wherever you go, you find friends who dig Gary Snyder, know where the best grass grows, and love all sentient creatures.

III

Youth is The Man of the Year. Marijuana parties and Vietnam demonstrations are overwhelmed by sociology students with true-or-false questionnaires and by Life photographers. What passes for analysis of what is happening is usually based on vestigial remnants of the sectarian Marxism of the years between the wars, as appropriate to contemporary problems as the speculations of the Gnostics.

“What goes on? I really wanna know,” says Donovan. First, the biological structure of the human race is changing. Most obviously man is growing younger. In both the wealthy and poor nations the majority of the population is under thirty, and soon the majority of the voting population will be in their twenties. Birth rates, death rates, infant mortality, age at sexual maturity, age at the onset of senescence, general health, causes of death, even height, weight, and condition of the teeth — all the statistics of public health have changed drastically in the last two decades and are still changing in the same directions. People under thirty don’t look like members of the same nation as their grandparents.

Mental health statistics, records of commitments to mental hospitals, prison populations, out-patient cases of neurosis and psychosis, arrests for petty crimes and disorders, juvenile delinquency, seem to be moving in the opposite direction. Mostly this is due to better diagnosis and treatment and to more thorough policing of the society. It is simply not true that “the tensions of life are greater now than they were a century ago,” as a reading of Engels’s Condition of the British Working Class or any of hundreds of similar works on the slum poor and the workers in mines and mills of those days will prove.

The poor didn’t have mental problems. Tension, like sexual intercourse in the old joke, was much too good for them. If they broke through the crust of society and disturbed their betters they were hauled off to court and jail. If they stayed in the slums they were allowed to stew in their own juice of crime undisturbed, or tried, convicted, and punished on the spot by the policeman’s club.

Today a skilled mechanic in a Stockholm suburb lives better than Gustavus Adolphus; that we know, but we seldom realize that in many ways a Negro family in San Francisco on welfare payments in a subsidized housing project lives better than Charlemagne. Both can afford tensions and neuroses which only fifty years ago were the exclusive privilege of the Viennese mercantile aristocracy.

In the years since the Second World War our ways of life have changed drastically, but they have lagged just as drastically behind the changes in technology, as technology still lags behind the changes in science itself. The well-educated layman over forty seldom has any notion of what has happened in biology, physics, astronomy, cosmology, since he read the ABC of Relativity and the popular works of Eddington and Jeans, just as the suburban housewife who switches on her “electronic oven” has any idea of how it works, or still less, of what technology could really do to housekeeping if it got the chance. We are still destroying the environment with a machine, the internal combustion automobile engine, which is totally obsolete, from the steering mechanism to the sales organization to the political disgrace of the Arab peninsula. A billion people still have unwanted children year after year. We still inhale clouds of carcinogens to relax our nerves. We still drink alcohol in poisonous concentrations. We still murder “niggers” in America and “gooks” in Vietnam. One third of the population is still, as FDR said, ill clothed, ill housed, and ill fed — in the civilized countries. In the world, nine-tenths of the people still live lives that are nasty, brutish, and short, and grow steadily worse.

Here, in the foregoing paragraphs, lies the explanation of what’s happening. The cybernetic, computerized, transistorized society is already here in potential and an ever-increasing number of people are insisting on walking into it and living there. We can afford peace, we can afford creative leisure, we can afford to demonstrate and revolt until we get them. A society in which hard labor is no longer the original source of value can afford to be good. The best and most effective demonstration is simply to start living by the new values. The people who do are going to outlive the people who don’t unless the oldies murder them all in their wars.

The past year has witnessed a tremendous step up in the tempo and force of protest and a great clarification of objectives. First of course is the Vietnam War. It is no longer safe for spokesmen for the Credibility Gap, otherwise known as the U.S. State Department and Executive, to appear on college campuses. They are physically attacked and driven from the platform and have to be rescued by helicopter from cellar exits. One of the most popular buttons amongst young Americans reads, “Lee Harvey Oswald, Where Are You Now That Your Country Needs You?” Students riot and go on general strikes when the Navy erects a recruiting booth on university property. You don’t have to take my word for it — Time magazine says so too.

What would have happened had there been no Vietnam War? Much the same thing but at a slower tempo. Vietnam, like Voltaire’s God, has been so convenient that, had it not have existed, it would have had to be invented. There is more than a stale joke here. All correspondents agree that the minute they land in Saigon, the brass overwhelms them with exhibitions of new hardware, like little children on Christmas morning. All wars, but Vietnam most especially, are characterized by a qualitative change in the technology, a “great leap forward” in which “quantity changes into quality,” to talk Marxist argot. Electronic search-and-destroy gimmicks above the jungles, and an indomitable demand to change completely the quality of life at home.

There are no Dutch troops in Vietnam, so the provos have been able to concentrate on resistance to the destruction of the environment by an outworn technology in the grip of mindless greed. From the point of view of an intelligent insect from Mars, there is a remarkable similarity. The fumes that make Amsterdam almost uninhabitable and the machines that clutter the streets and destroy all the advantages and pleasures of men living together in cities — these differ from napalm only in being slower in their effects — it is all gasoline in one form or another. For “politics” in Clausewitz’s maxim, substitute “technology.”

Against cigarettes, against hard alcohol, against sexual hypocrisy, against political fraud, against the commodity culture of conspicuous expenditure, against the dead hand of the past armed with a police truncheon that opposes all motion into the future — for the ancient theological virtues, voluntary poverty — the rejection of the destructive lures of a predatory society, the chastity of sexual honesty, and obedience to personal integrity . . . it is very convenient to the social critic that the youth of Amsterdam should have been able to define their program so clearly, unconfused by the vast evil that hangs in a cloud over America. Is this anarchism? If anarchism is the realization that the ballot is a paper substitute for the bullet, the bayonet, and the billy, that liberty is the mother, not the daughter of order, and that property in the means of life is robbery, it is anarchism. Certainly there is no important difference between the anti-programmatic programs of youth in Amsterdam, Stockholm, and San Francisco. The fundamentals stand out clearer in the smoggy air of Amsterdam, that is all. As jazz musicians say, we need a new book.

The great difference between Europe and America is on the other side, amongst the old whisky drinkers, as American youth now call them. Europe lies under a dictatorship of the aged. Willy Brandt, Günter Grass, Harold Wilson, these are professional young men grown old. Who represents “youth” in France? A mummified boy adventurer from the Chinese and Spanish Revolutions, a kind of political Jean Cocteau . . . really a horrifying vision. A politician like Kiesinger, who has been as carefully manufactured as a TV image as ever was Nixon, Kennedy, and Reagan, to whom is he manufactured to appeal to? The young? Indeed not. People all over recently were crying about the comeback of Nazism in the provincial elections. Kiesinger has been constructed to appeal to the stay put, not the come back. His publicity image is that of a kind of Talleyrand or Abbé Sieyès of a half-century of lost revolutions, wholesale betrayals, and genocide on all hands. His appeal is aimed at a target distinguishable by the same gleam of silver hair as his own head.

In America things are different. This is the land of highly developed consumer research. What’s the Target? Youth. What’s the hottest commodity along Mad Alley? Revolt. God knows, I was told that on Madison Avenue in the executive office of MCA ten years ago, when they wanted to take me over as a stellar attraction.

So the Republican rebirth in the November election was a kind of youth revolt . . . a revolt of aging youth who are entering income brackets they never knew existed until they got their tax forms. Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, Oregon, the winners were all presented as idealized junior executive types. Where this was impossible, as in the case of Reagan, who is about as old as I am, liberal applications of pancake makeup, Man-Tan, mascara, hair dye, pep pills, and the experience of a lifetime playing good cowboys produced a reasonable facsimile thereof, if not youth itself. Reagan’s opponent, Pat Brown, looked old and tired and vulgar in his cradle.

Johnson the Second and his successors are old men with old ways and old solutions for old problems, whatever their ages. Most of them are men of the Cold War, if not of the New Deal, the Spanish Civil War, and the Moscow Trials. What everyone realizes, except themselves, about the Vietnam War is that, blood and horror disregarded, it is inappropriate — it is an obsolete answer. The 1968 national election was a contest (as will be the 1972) between the draft-card burners and the IBM branch managers, young youth against old youth . . . the audiences of Bob Dylan versus the audiences of Dave Brubeck. I think from the point of view of older societies, in both senses, American politics in the coming years is going to seem very odd indeed. The Declaration of Independence, the Communist Manifesto, Mein Kampf, these are totally obsolete as rhetorical manuals. The new styles are to be found in Seventeen, Mademoiselle, and Playboy. Or so the million-dollar public-relations firms believe. The backwash into Europe is going to be interesting to observe. Even more interesting is going to be the youth backlash — the response of the target itself. Besides being anti-anti-life, the young are also anti-manipulation, or is that the same thing?

KENNETH REXROTH

1967-1969

Pot of Tage

SF History Home SF History Home

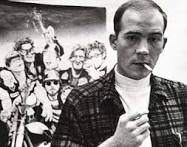

The Hippies – By Hunter S. Thompson

Thursday, July 13, 2006 The best year to be a hippie was 1965, but then there was not much to write about, because not much was happening in public and most of what was happening in private was illegal. The real year of the hippie was 1966, despite the lack of publicity, which in 1967 gave way to a nationwide avalanche in Look, Life, Time, Newsweek, the Atlantic, the New York Times, the Saturday Evening Post, and even the Aspen Illustrated News, which did a special issue on hippies in August of 1967 and made a record sale of all but 6 copies of a 3,500-copy press run. But 1967 was not really a good year to be a hippie. It was a good year for salesmen and exhibitionists who called themselves hippies and gave colorful interviews for the benefit of the mass media, but serious hippies, with nothing to sell, found that they had little to gain and a lot to lose by becoming public figures. Many were harassed and arrested for no other reason than their sudden identification with a so-called cult of sex and drugs. The publicity rumble, which seemed like a joke at first, turned into a menacing landslide. So quite a few people who might have been called the original hippies in 1965 had dropped out of sight by the time hippies became a national fad in 1967.

Ten years earlier the Beat Generation went the same confusing route. From 1955 to about 1959 there were thousands of young people involved in a thriving bohemian subculture that was only an echo by the time the mass media picked it up in 1960. Jack Kerouac was the novelist of the Beat Generation in the same way that Ernest Hemingway was the novelist of the Lost Generation, and Kerouac’s classic “beat” novel, On the Road, was published in 1957. Yet by the time Kerouac began appearing on television shows to explain the “thrust” of his book, the characters it was based on had already drifted off into limbo, to await their reincarnation as hippies some five years later. (The purest example of this was Neal Cassidy [Cassady], who served as a model for Dean Moriarity in On the Road and also for McMurphy in Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.) Publicity follows reality, but only up to the point where a new kind of reality, created by publicity, begins to emerge. So the hippie in 1967 was put in the strange position of being an anti-culture hero at the same time as he was also becoming a hot commercial property. His banner of alienation appeared to be planted in quicksand. The very society he was trying to drop out of began idealizing him. He was famous in a hazy kind of way that was not quite infamy but still colorfully ambivalent and vaguely disturbing.

Despite the mass media publicity, hippies still suffer or perhaps not from a lack of definition. The Random House Dictionary of the English Language was a best seller in 1966, the year of its publication, but it had no definition for “hippie.” The closest it came was a definition of “hippy”: “having big hips; a hippy girl.” Its definition of “hip” was closer to contemporary usage. “Hip” is a slang word, said Random House, meaning “familiar with the latest ideas, styles, developments, etc.; informed, sophisticated, knowledgeable [?].” That question mark is a sneaky but meaningful piece of editorial comment.

Everyone seems to agree that hippies have some kind of widespread appeal, but nobody can say exactly what they stand for. Not even the hippies seem to know, although some can be very articulate when it comes to details.

“I love the whole world,” said a 23-year-old girl in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district, the hippies’ world capital. “I am the divine mother, part of Buddha, part of God, part of everything.

“I live from meal to meal. I have no money, no possessions. Money is beautiful only when it’s flowing; when it piles up, it’s a hang-up. We take care of each other. There’s always something to buy beans and rice for the group, and someone always sees that I get ‘grass’ [marijuana] or ‘acid’ [LSD]. I was in a mental hospital once because I tried to conform and play the game. But now I’m free and happy.” She was then asked whether she used drugs often. “Fairly,” she replied. “When I find myself becoming confused I drop out and take a dose of acid. It’s a short cut to reality; it throws you right into it. Everyone should take it, even children. Why shouldn’t they be enlightened early, instead of waiting till they’re old? Human beings need total freedom. That’s where God is at. We need to shed hypocrisy, dishonesty, and phoniness and go back to the purity of our childhood values.”

The next question was “Do you ever pray?” “Oh yes,” she said. “I pray in the morning sun. It nourishes me with its energy so I can spread my love and beauty and nourish others. I never pray for anything; I don’t need anything. Whatever turns me on is a sacrament: LSD, sex, my bells, my colors…. That’s the holy communion, you dig?” That’s about the most definitive comment anybody’s ever going to get from a practicing hippie. Unlike beatniks, many of whom were writing poems and novels with the idea of becoming second-wave Kerouacs or Allen Ginsbergs, the hippie opinion makers have cultivated among their followers a strong distrust of the written word. Journalists are mocked, and writers are called “type freaks.” Because of this stylized ignorance, few hippies are really articulate. They prefer to communicate by dancing, or touching, or extrasensory perception (ESP). They talk, among themselves, about “love waves” and “vibrations” (“vibes”) that come from other people. That leaves a lot of room for subjective interpretation, and therein lies the key to the hippies’ widespread appeal.

This is not to say that hippies are universally loved. From coast to coast, the forces of law and order have confronted the hippies with extreme distaste. Here are some representative comments from a Denver, Colo., police lieutenant. Denver, he said, was becoming a refuge for “long-haired, vagrant, antisocial, psychopathic, dangerous drug users, who refer to themselves as a ‘hippie subculture a group which rebels against society and is bound together by the use and abuse of dangerous drugs and narcotics.” They range in age, he continued, from 13 to the early 20’s, and they pay for their minimal needs by “mooching, begging, and borrowing from each other, their friends, parents, and complete strangers…. It is not uncommon to find as many as 20 hippies living together in one small apartment, in communal fashion, with their garbage and trash piled halfway to the ceiling in some cases.”

One of his co-workers, a Denver detective, explained that hippies are easy prey for arrests, since “it is easy to search and locate their drugs and marijuana because they don’t have any furniture to speak of, except for mattresses lying on the floor. They don’t believe in any form of productivity,” he said, “and in addition to a distaste for work, money, and material wealth, hippies believe in free love, legalized use of marijuana, burning draft cards, mutual love and help, a peaceful planet, and love for love’s sake. They object to war and believe that everything and everybody except the police are beautiful.”

Many so-called hippies shout “love” as a cynical password and use it as a smokescreen to obscure their own greed, hypocrisy, or mental deformities. Many hippies sell drugs, and although the vast majority of such dealers sell only enough to cover their own living expenses, a few net upward of $20,000 a year. A kilogram (2.2 pounds) of marijuana, for instance, costs about $35 in Mexico. Once across the border it sells (as a kilo) for anywhere from $150 to $200. Broken down into 34 ounces, it sells for $15 to $25 an ounce, or $510 to $850 a kilo. The price varies from city to city, campus to campus, and coast to coast. “Grass” is generally cheaper in California than it is in the East. The profit margin becomes mind-boggling regardless of the geography when a $35 Mexican kilogram is broken down into individual “joints,” or marijuana cigarettes, which sell on urban street corners for about a dollar each. The risk naturally increases with the profit potential. It’s one thing to pay for a trip to Mexico by bringing back three kilos and selling two in a circle of friends: The only risk there is the possibility of being searched and seized at the border. But a man who gets arrested for selling hundreds of “joints” to high school students on a St. Louis street corner can expect the worst when his case comes to court.

The British historian Arnold Toynbee, at the age of 78, toured San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district and wrote his impressions for the London Observer. “The leaders of the Establishment,” he said, “will be making the mistake of their lives if they discount and ignore the revolt of the hippies and many of the hippies’ non hippie contemporaries on the grounds that these are either disgraceful wastrels or traitors, or else just silly kids who are sowing their wild oats.”

Toynbee never really endorsed the hippies; he explained his affinity in the longer focus of history. If the human race is to survive, he said, the ethical, moral, and social habits of the world must change: The emphasis must switch from nationalism to mankind. And Toynbee saw in the hippies a hopeful resurgence of the basic humanitarian values that were beginning to seem to him and other long-range thinkers like a tragically lost cause in the war-poisoned atmosphere of the 1960’s. He was not quite sure what the hippies really stood for, but since they were against the same things he was against (war, violence, and dehumanized profiteering), he was naturally on their side, and vice versa.

There is a definite continuity between the beatniks of the 1950’s and the hippies of the 1960’s. Many hippies deny this, but as an active participant in both scenes, I’m sure it’s true. I was living in Greenwich Village in New York City when the beatniks came to fame during 1957 and 1958. I moved to San Francisco in 1959 and then to the Big Sur coast for 1960 and 1961. Then after two years in South America and one in Colorado, I was back in San Francisco, living in the Haight-Ashbury district, during 1964, 1965, and 1966. None of these moves was intentional in terms of time or place; they just seemed to happen. When I moved into the Haight-Ashbury, for instance, I’d never even heard that name. But I’d just been evicted from another place on three days’ notice, and the first cheap apartment I found was on Parnassus Street, a few blocks above Haight.

At that time the bars on what is now called “the street” were predominantly Negro. Nobody had ever heard the word “hippie,” and all the live music was Charlie Parker-type jazz. Several miles away, down by the bay in the relatively posh and expensive Marina district, a new and completely unpublicized nightclub called the Matrix was featuring an equally unpublicized band called the Jefferson Airplane. At about the same time, hippie author Ken Kesey (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 1962, and Sometimes a Great Notion, 1964) was conducting experiments in light, sound, and drugs at his home at La Honda, in the wooded hills about 50 miles south of San Francisco. As the result of a network of circumstance, casual friendships, and connections in the drug underworld, Kesey’s band of Merry Pranksters was soon playing host to the Jefferson Airplane and then to the Grateful Dead, another wildly electric band that would later become known on both coasts along with the Airplane as the original heroes of the San Francisco acid-rock sound. During 1965, Kesey’s group staged several much-publicized Acid Tests, which featured music by the Grateful Dead and free Kool-Aid spiked with LSD. The same people showed up at the Matrix, the Acid Tests, and Kesey’s home in La Honda. They wore strange, colorful clothes and lived in a world of wild lights and loud music. These were the original hippies.

It was also in 1965 that I began writing a book on the Hell’s Angels, a notorious gang of motorcycle outlaws who had plagued California for years, and the same kind of weird coincidence that jelled the whole hippie phenomenon also made the Hell’s Angels part of the scene. I was having a beer with Kesey one afternoon in a San Francisco tavern when I mentioned that I was on my way out to the headquarters of the Frisco Angels to drop off a Brazilian drum record that one of them wanted to borrow. Kesey said he might as well go along, and when he met the Angels he invited them down to a weekend party in La Honda. The Angels went and thereby met a lot of people who were living in the Haight-Ashbury for the same reason I was (cheap rent for good apartments). People who lived two or three blocks from each other would never realize it until they met at some pre-hippie party. But suddenly everybody was living in the Haight-Ashbury, and this accidental unity took on a style of its own. All that it lacked was a label, and the San Francisco Chronicle quickly came up with one. These people were “hippies,” said the Chronicle, and, lo, the phenomenon was launched. The Airplane and the Grateful Dead began advertising their sparsely attended dances with psychedelic posters, which were given away at first and then sold for $1 each, until finally the poster advertisements became so popular that some of the originals were selling in the best San Francisco art galleries for more than $2,000. By this time both the Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead had gold-plated record contracts, and one of the Airplane’s best numbers, “White Rabbit,” was among the best-selling singles in the nation.

By that time, too, the Haight-Ashbury had become such a noisy mecca for freaks, drug peddlers, and curiosity seekers that it was no longer a good place to live. Haight Street was so crowded that municipal buses had to be rerouted because of the traffic jams.

At the same time, the “Hashbury” was becoming a magnet for a whole generation of young dropouts, all those who had canceled their reservations on the great assembly line: the high-rolling, soul-bending competition for status and security in the ever-fattening yet ever-narrowing American economy of the late 1960’s. As the rewards of status grew richer, the competition grew stiffer. A failing grade in math on a high school report card carried far more serious implications than simply a reduced allowance: It could alter a boy’s chances of getting into college and, on the next level, of getting the “right job.” As the economy demanded higher and higher skills, it produced more and more technological dropouts. The main difference between hippies and other dropouts was that most hippies were white and voluntarily poor. Their backgrounds were largely middle class; many had gone to college for a while before opting out for the “natural life”à an easy, unpressured existence on the fringe of the money economy. Their parents, they said, were walking proof of the fallacy of the American notion that says “work and suffer now; live and relax later.”

The hippies reversed that ethic. “Enjoy life now,” they said, “and worry about the future tomorrow.” Most take the question of survival for granted, but in 1967, as their enclaves in New York and San Francisco filled up with penniless pilgrims, it became obvious that there was simply not enough food and lodging.

A partial solution emerged in the form of a group called the Diggers, sometimes referred to as the “worker-priests” of the hippie movement. The Diggers are young and aggressively pragmatic; they set up free lodging centers, free soup kitchens, and free clothing distribution centers. They comb hippie neighborhoods, soliciting donations of everything from money to stale bread and camping equipment. In the Hashbury, Diggers’ signs are posted in local stores, asking for donations of hammers, saws, shovels, shoes, and anything else that vagrant hippies might use to make themselves at least partially self-supporting. The Hashbury Diggers were able, for a while, to serve free meals, however meager, each afternoon in Golden Gate Park, but the demand soon swamped the supply. More and more hungry hippies showed up to eat, and the Diggers were forced to roam far afield to get food.

The concept of mass sharing goes along with the American Indian tribal motif that is basic to the whole hippie movement. The cult of tribalism is regarded by many as the key to survival. Poet Gary Snyder, one of the hippie gurus, or spiritual guides, sees a “back to the land” movement as the answer to the food and lodging problem. He urges hippies to move out of the cities, form tribes, purchase land, and live communally in remote areas. By early 1967 there were already a half dozen functioning hippie settlements in California, Nevada, Colorado, and upstate New York. They were primitive shack-towns, with communal kitchens, half-alive fruit and vegetable gardens, and spectacularly uncertain futures. Back in the cities the vast majority of hippies were still living from day to day. On Haight Street those without gainful employment could easily pick up a few dollars a day by panhandling. The influx of nervous voyeurs and curiosity seekers was a handy money-tree for the legion of psychedelic beggars. Regular visitors to the Hashbury found it convenient to keep a supply of quarters in their pockets so that they wouldn’t have to haggle about change. The panhandlers were usually barefoot, always young, and never apologetic. They would share what they collected anyway, so it seemed entirely reasonable that strangers should share with them. Unlike the beatniks, few hippies are given to strong drink. Booze is superfluous in the drug culture, and food is regarded as a necessity to be acquired at the least possible expense. A “family” of hippies will work for hours over an exotic stew or curry, but the idea of paying three dollars for a meal in a restaurant is out of the question.