Bob Weir Biography

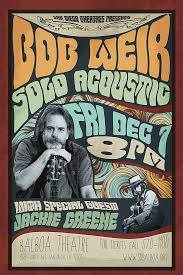

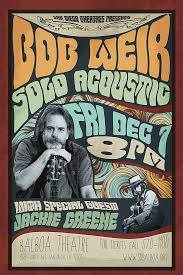

Environmental Activist, Guitarist (1947–)

Quick Facts

Name Bob Weir Occupation Environmental Activist, Guitarist Birth Date October 16, 1947 (age 66) Education Menlo Atherton High School, Fountain Valley High School Place of Birth San Francisco, California AKA Bob WeirFull Name Robert Hall Weir Zodiac Sign Libra

Synopsis

Early Life

Musical Career

Personal Life

Cite This Page

Bob Weir was a rhythm guitarist for the legendary rock band the Grateful Dead from 1964 to 1995 and later reunited to tour with former members as The Other Ones.

Synopsis

Guitarist Bob Weir was born on October 16, 1947 in San Francisco, California. In 1964, he started a band that was eventually called the Grateful Dead, with Jerry Garcia and Ron McKernan. In 1972, Weir put out his first solo album. He also performed with other bands throughout his time with the Dead. After Garcia died in 1995, Weir toured with RatDog, and later reunited with former Dead members to tour.

Early Life

Bob Weir was born October 16, 1947, in San Francisco, California. He was raised by wealthy adoptive parents in the suburban town of Atherton, California.

Weir started playing guitar at the age of 13. As a teen, Weir first attended Menlo Atherton High School, but his struggles with undiagnosed dyslexia and his poor academic performance led his exasperated parents to send him away to boarding school. There, at Fountain Valley High School, Weir met John Perry Barlow, who would later write lyrics for the Grateful Dead. After Weir was kicked out of Fountain Valley, he spent most of his time hanging out in Palo Alto, California, checking out the Bay Area folk-rock scene. He spent his days at a record store where Jerry Garcia gave guitar lessons, and his nights at a club called the Tangent. At the Tangent, Weir had the good fortune to see several rock legends in the making, including Janis Joplin, Jefferson Airplane and the familiar face from the music shop, Jerry Garcia.

Musical Career

In 1964, when Weir was just 17, Garcia convinced him and Ron “Pigpen” McKernan to start a folk-rock and blues band called Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions, with Weir as their rhythm guitarist. After first renaming the band the Warlocks, the band eventually settled on the name the Grateful Dead and expanded to include drummers Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann, bass guitarist Phil Lesh and several different keyboardists over the life of the group.

Although the Dead played nearly 100 shows yearly throughout the 1970s, Weir also participated in other musical projects during this time. In 1972 he put out his first solo album, called Ace. He also performed and recorded with other bands, including Kingfish, in the 1970s. In the early 1980s Weir toured with Bobby and the Midnites and contributed to recording two albums with the band. During this time he met recording session musician Brent Mydland, whom he would invite to join the Grateful Dead as a keyboardist in 1979.

Weir refocused primarily on playing with the Grateful Dead in the late 1980s and continued to tour with them extensively until Jerry Garcia’s death in 1995. After Garcia died, Weir started touring nonstop with RatDog, the band he had recently started with bassist Rob Wasserman. In 1998 Weir reunited with remaining members of the Grateful Dead under the band name The Other Ones. The Other Ones recorded a new album in 1999 and toured in 2000, the same year RatDog’s first album was released.

Weir would tour with former Grateful Dead band members again in 2009. The 2009 tour made Weir and Lesh nostalgic for the band’s old chemistry, leading them to combine members of the Dead and RatDog to form a new successful band called Furthur.

Personal Life

While Weir has devoted most of his time and energy to music, he has also been active in a number of social causes. He’s been a board member of Seva, a foundation that combats blindness in South America and Asia, and has also been an activist for Greenpeace. Together, Weir and members of the Dead formed the Rex Foundation, which provides community support for creative endeavors.

In his off-stage life, Weir also has two daughters—Monet and Chloe—with Natascha Müenter, whom he married in 1999.

Robert Hall Weir. (2014). The Biography.com website. Retrieved 05:07, May 08, 2014, from http://www.biography.com/people/bob-weir-20878671.

“Robert Hall Weir.” 2014. The Biography.com website. May 08 2014 http://www.biography.com/people/bob-weir-20878671.

BLACK THROATED WIND BY BOB WEIR

April 28, 2014

Grateful for Bo

Posted by Alec Wilkinson

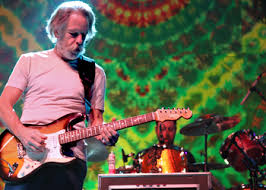

I went to the Tribeca Film Festival to see “The Other One: The Long, Strange Trip of Bob Weir,” because I have always liked Bob Weir, the second guitarist of the Grateful Dead. Usually you would call such a musician a rhythm guitarist, but Weir isn’t anything like a garden-variety rhythm guitarist. To the initial exasperation of his bandmates, who wanted someone to keep time more diligently, he developed one of the most unusual styles in rock and roll, built on lyric asides and cunning contrapuntal remarks that suggest a line of melody travelling through the map of the chord changes.

The Grateful Dead embodied a singular approach to the mathematics of simple song forms. It occurs to me that it represented something like a model of the unconscious as it rises into awareness. The patterns of the drummers, Bill Kreutzmann and Mickey Hart, suggested pressing impulses and intuitions, the way some poets describe hearing the rhythms of the words before the words arrive. Phil Lesh’s bass playing, the rudiments of which were taken from classical music, especially Bach and Beethoven, amounted to a layer of permeable ground. He was sometimes engaged with the drums and sometimes with the stringed instruments in the range above his own. Jerry Garcia’s guitar was the conversational voice, articulating the thoughts that ascended to the level of social discourse. In between was Weir, following the example of the left hand of the pianist McCoy Tyner, he told me years ago, inverting chords and finding passing phrases among them, mostly supporting but sometimes subverting, too.

Not that the endeavor always succeeded. There were fallow periods, periods of fatigue, and periods when Garcia’s health and drug problems seemed to dog and shadow the music. There were nights of singing and playing out of tune, of being out of sorts, and there were nights when at least one member was not entirely sober. In what they were attempting, failure is, anyway, easier to achieve than success.

Weir is a modest man, unassuming, a gentleman. He says in the movie that he takes no pride in what he has accomplished, because he regards pride as a suspect emotion. He began playing in the jug band that became the Grateful Dead when he was sixteen years old. He would arrive at his parents’ house sometimes at daybreak, after playing all night with the band, and have breakfast and go to school. Eventually, school fell aside. His mother told him that she and her husband and their daughter, Wendy, were a family and that they could no longer live with his comings and goings, and so he left and moved into a house with the band. He ran away with the circus, he says.

His nickname for a time was Mr. Bob Weir Trouble. He threw a water balloon at a cop from the roof and was arrested. When he learned that the draft board had to save every piece of correspondence from a citizen, he began sending his draft board stones and sticks and anything he could fit into a mailbox. At an airline counter, he produced a cap pistol and started playing cowboys and Indians, which got the Grateful Dead banned from the airline. His roommate at the band’s house was Neal Cassady, who is Dean Moriarty in Kerouac’s “On the Road.” Weir’s most widely performed song, “The Other One,” which the Grateful Dead played often, in variations, for nearly thirty years, describes his flight from home, with Cassady driving Furthur, the Merry Pranksters’ bus. Weir says that he never listens to old Grateful Dead music, and in the movie he says that the pleasure he took in the band’s first gold record was in being able to give it to his parents and show them that he had accomplished something. Weir was briefly in the audience for the movie, with his wife and his younger daughter—his older daughter was home in California, rehearsing for a school play. I happened to be sitting about four seats from him. I was curious to see how long he could stand to watch himself onscreen. Roughly ten minutes in, he rose and disappeared down a hallway, and didn’t come back. At the end of the movie, he performed for about forty-five minutes.

The last thing I want to say is that I saw the Grateful Dead for the first time, at the Fillmore East, in the fall of 1969, when they were still essentially a regional California attraction. I had gone with friends to the Saturday-night late show to see my favorite band at the time, Country Joe and the Fish, who were the headliners. Bill Graham announced that the order of the concert would be reversed, and that Country Joe would play first. This was to accommodate the Grateful Dead, who were known to play for hours.

The Fillmore was a small theatre. I was sitting in the third row. Not long after the Grateful Dead took the stage, at around one or two in the morning, I fell asleep, for how long I have no idea. I tried not to, but I was seventeen years old, and not used to staying up late. I kept feeling my chin fall forward, and then I would open my eyes to a different tableau, which gave the concert the atmosphere of a dream. Country Joe had performed as a band. The Grateful Dead took the stage like a troupe of minstrels. There were seven of them: two drummers, two guitarists (Weir and Garcia), a bass player, a man who played the piano and the organ, and Pigpen, a small, slight figure in denim, with a thin beard and a crumpled hat, who sometimes played the organ, sometimes the conga drums, and other times just wandered around the stage, standing in front of the other musicians and pointing a camera at them. Sometimes, one of the drummers got up from his kit, walked over, and struck a gong or shook bells, like a shepherd. A man who looked like a gang biker came from the wings now and then, and knelt and held a cigarette lighter to a tube on the floor, and an arrow of flames shot toward the ceiling, like those flames on top of gas wells. The fronts of all the amplifiers were covered with elaborately tie-dyed fabric and were lavish and arresting to look at, like something from a bazaar in a country it was difficult to reach and a little scary to visit. An intricate wooden sign, embedded with lights, descended from the ceiling. It read “Grateful Dead” in the same curving, mysterious, psychedelic font as the cover of their album “Aoxomoxoa,” a nonsensical palindrome.

I was a senior in high school. The spooky flames, the disorder that seemed only half under control, the carnival atmosphere, and the powerful, serpentine music were my first awarenesses that the world was deeper, more capacious, and more thrilling than I knew. I thought that the music I was hearing would need hieroglyphs, not notes, to represent it. Weir played his guitar as if he were exploring it, with curiously studious gestures. Rhythm guitarists in those days strummed. Weir, however, appeared to be apprehending and enacting possibilities within the fabric of the music. The band itself seemed like the exemplification of a mystery, and the musicians like sorcerers. They were young men then, all in their twenties, and they had a great deal of energy. My friends and I had gone into the theatre a little before midnight, and by the time the concert was over and the doors had opened, the sun had risen. People who had slept all night were walking on Second Avenue in their day clothes. The sudden transit from darkness to daylight made it seem as if I had emerged from a forest or a tunnel. I remember a man carrying a copy of the Sunday Times and a container of coffee. He seemed, obscurely, to have the faintest head start in time on me. We found my friend’s car and drove home to the suburbs and our parents’ houses. I now knew something that they didn’t know: life is more than we imagine it to be.

Perhaps 1969 was late to be arriving at such an awareness, but it wasn’t so late for a boy at a school in the suburbs of New York. A few of my friends seemed to know about it, but not everyone. It was still a secret to hold, a freemasonry. And what is adolescence but the reducing of the world to a manageable idea that you can share safely with others.

Read “Deadhead,” Nick Paumgarten’s piece about the vast recorded legacy of the Grateful Dead, and Alec Wilkinson’s Talk of the Town stories about Weir, “Blind Date” and “The Musical Life.”

Copyright ©1987 Robbi Cohen/Dead images