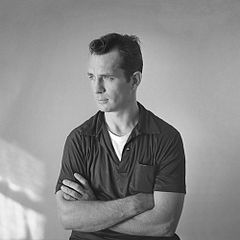

counterculture icon

-

Bob Dylan performing at a civil rights rally in Washington D.C. on August 28, 1963. Photo: Getty Images

-

Photo: Getty Images

Photo: Getty ImagesBob Dylan and singer Joan Baez in Embankment Gardens, London in 1963. Photo: Getty Images

Bob Dylan, the surprise winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature on Thursday, became an icon of the 1960s counterculture, but his voice has reached widely and evocatively into the American past.

The author of some of rock’s early anthems such as “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” the poet of pop tapped classic folk and gospel songs to rejuvenate defining US forms of story-telling.

Since early in his career, the 75-year-old singer has experimented with the intersection of the literary and the musical.

In the words of a reviewer in The New York Times, who saw the then 21-year-old perform solo at Town Hall theater in 1963, “Mr. Dylan’s words and melodies sparkle with the light of an inspired poet.”

One of his most celebrated songs, “Mr. Tambourine Man,” features a literary character based on a drummer Dylan knew from the clubs of New York’s Greenwich Village.

“Like a Rolling Stone” tore apart pop convention by going on for more than six minutes, with Dylan’s steady narration and a touch of R&B interrupted by the refrain, “How does it feel?”

“After writing that, I wasn’t interested in writing a novel or a play or anything, like I knew like I had too much. I wanted to write songs,” Dylan said later of the song.

“Desolation Row,” which closed his 1965 album “Highway 61 Revisited,” stretched on for more than 11 minutes and reached into biblical allusions, while referencing the growing tumult in urban America.

“Highway 61 Revisited” itself reflected an American journey, referencing the highway that stretches from Dylan’s home of Minnesota to New Orleans and the homes of the blues in the American South.

The album was part of a massive burst of creativity when in a two-year period Dylan put out three legendary albums, with the other two being “Bringing It All Back Home” and “Blonde on Blonde.”

Rise to stardom

The stardom is all a long way from his humble beginnings as Robert Allen Zimmerman, born in 1941 in Duluth, Minnesota.

He taught himself to play the harmonica, guitar and piano. Captivated by the music of folk singer Woody Guthrie, Zimmerman changed his name to Bob Dylan — reportedly after the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas — and began performing in local nightclubs.

After dropping out of college, he moved to New York in 1960. His first album contained only two original songs, but the 1963 breakthrough “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan” featured a slew of his own work, including the classic “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

Armed with a harmonica and an acoustic guitar, Dylan confronted social injustice, war and racism, quickly becoming a prominent civil rights campaigner — and recording an astonishing 300 songs in his first three years.

His interest in civil rights has persisted and in 1991 he released “Blind Willie McTell,” one of the best-known songs of his late career in which Dylan reflects on slavery through the story of the blues singer of the same name.

In 1965, Dylan also was behind a symbolic turning point in music when he went electric at the Newport Folk Festival, turning on the amplifiers for a stunned audience.

As Dylan toured Europe afterward, he was met with hostility with an audience member in England even denouncing him as “Judas” over the betrayal of his folk roots.

When Dylan afterward played in France, the tensions had become so raw that he even held a news conference with a puppet, to which he would sarcastically put his ear as if seeking counsel to reporters’ questions.

”Sound like a frog’

Despite his massive cultural influence, Dylan has remained an enigmatic presence. With his gravelly tone, he has long won acclaim in spite of rather than because of his voice.

“Critics have been giving me a hard time since Day One. Critics say I can’t sing. I croak. Sound like a frog,” Dylan said last year in an unexpected career-spanning speech as he accepted a lifetime award at the Grammys.

His relationship with crowds is borders on indifference to hostile, with Dylan steadfastly refusing to please audiences by rolling out his hits.

Performing Friday at the inaugural Desert Trip festival of rock elders in California, Dylan did not say a word to the crowd and kept his back turned, not allowing overhead footage of him for the majority of the audience that could not see. In one turn that surprised fans, Dylan — raised a secular Jew — became a born-again Christian in the late 1970s after taking up Bible study following his divorce from his first wife, Sara. Dylan soon played down the Christianity, saying his conversion had been hyped by the media that he was agnostic at heart. He raised controversy again when he played in 1985 at the Live Aid concerts for Ethiopian famine relief and told the crowd that he wished “a little bit” of the money could go to American farmers struggling to pay their mortgages. His quip quickly created momentum as Willie Nelson and other artists set up Farm Aid, a still-running US festival to raise money for farmers.

Dylan has remained active and toured regularly. In 2012, he released an album full of dark tales of the American past called “Tempest,” raising speculation it would be his finale, in an echo of Shakespeare’s last play of the same name.

But Dylan has kept up his prolific output. Earlier this year he released his 37th studio album, his second in a row devoted to pop standards popularized by Frank Sinatra.

Keywords: Bob Dylan, Nobel prize for Literature