Road Ready

‘The Voice Is All,’ by Joyce Johnson

By JAMES CAMPBELL

Published: January 18, 2013

In January 1949, Jack Kerouac failed to appear for an afternoon date with a woman called Pauline. He had told Allen Ginsberg he planned to marry her — “the finest woman I’ll ever know” — once she had unshackled herself from her truck-driver husband, who, according to Joyce Johnson, was accustomed to “slapping her around to keep her in line.” In the meantime, Kerouac began an affair with Adele Morales (later to become the second Mrs. Norman Mailer). His failure to keep the rendezvous with Pauline, however, had nothing to do with affection for Adele; rather, he had overslept after a night of sex games with Luanne Henderson, whom Jack’s muse Neal Cassady had married when she was 15, and who, according to their friend Hal Chase, was “quite easy to get . . . into bed.” The tryst had been engineered by Cassady, who was hoping to watch, Johnson says, to show Luanne, by then 18, “how little she meant to him.” Two days later, Kerouac called on Ginsberg and found Luanne “covered with bruises from a beating Neal had given her.” Johnson describes Kerouac as “shocked” by the sight; nevertheless, “they all went out to hear bebop,” partly financed by money stolen by Cassady. In response to being jilted, Pauline confessed her affair to her husband, who tried to burn her on the stove. Kerouac described her in his journal as a “whore.” All the while, Ginsberg can be heard in the background: “How did we get here, angels?”

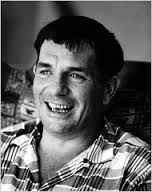

Collection of Allen Ginsberg, via Sotheby’s

Jack Kerouac in his Columbia University football uniform, 1940s.

<nyt_pf_inline>

THE VOICE IS ALL

The Lonely Victory of Jack Kerouac

By Joyce Johnson

489 pp. Viking. $32.95.

Related

-

Times Topic: Jack Kerouac

This is an everyday story of the Beat Generation in late-1940s New York, a tale of crazy mixed-up kids who took a lot of drugs, dabbled in criminality — with two homicides among the statistics — lapsed into madness, were fond of identifying one another as “saints, saints,” but often had the barest notion of what it means to respect the individuality of other human beings. Yet three members of the inner circle, Kerouac, Ginsberg and William Burroughs, created experimental literary works of remarkable originality — in particular, “On the Road,” “Kaddish” and “Naked Lunch” — which read as freshly today as they did 50 years ago; perhaps, in an instance of that trick that the best art sometimes plays on us, more so.

Kerouac certainly makes a good subject, but there already exist about a dozen biographies (by Ann Charters, Barry Miles, Gerald Nicosia, among others), not to mention memoirs, an oral history — the excellent “Jack’s Book” (1978) — and wider surveys of the Beat Generation. In “Minor Characters” (1983), Johnson wrote about her affair with Kerouac at the time of publication of “On the Road.” She now steps back to a period of Kerouac’s life with which she has no direct acquaintance, tracing the story from his origins in a French Canadian family in Lowell, Mass., to New York in 1951, where the book ends with a rare citation from Kerouac’s journals: “I’m lost, but my work is found.”

Johnson justifies the retelling of what is in outline a familiar tale by the fact of having gained access to the vast Kerouac archive, “deposited in the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library in 2002.” So far, so good. No large-scale Kerouac biography, so far as I am aware (“The Voice Is All” lacks a bibliography), has appeared since that date. Unfortunately, Johnson was apparently refused permission to quote at length from the journals and working drafts among Kerouac’s papers. The result is a life in paraphrase.

The method gives rise to frustration. In 1945, for example, Kerouac began writing a novel called “I Wish I Were You,” a reworking of the story of the killing of David Kammerer by Lucien Carr in 1944. Together, Kerouac and Burroughs had previously written “And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks,” a collaboration on the same subject that eventually saw the light of day in 2008. According to Johnson, “I Wish I Were You” is a different beast: “In two successive drafts of the first 100 pages, Jack put in all the textural detail that had been left out of ‘Hippos’ and even returned with renewed confidence to the lyricism he had abandoned just the year before. It was really quite brilliant, the best prose he had written so far