TO SET THE MOOD MUSIC -THE BRITISH INVASION

ENGLAND IN THE 60’S ARTICLE 1

Ancient elegance and new opulence are all tangled up in a dazzling blur of op and pop.

For a few years in the 1960s, London was the world capital of cool. When Time magazine dedicated its 15 April 1966 issue to London: the Swinging City, it cemented the association between London and all things hip and fashionable that had been growing in the popular imagination throughout the decade.

ENGLAND IN THE 60’S ARTICLE 2

London’s remarkable metamorphosis from a gloomy, grimy post-War capital into a bright, shining epicentre of style was largely down to two factors: youth and money. The baby boom of the 1950s meant that the urban population was younger than it had been since Roman times. By the mid-60s, 40% of the population at large was under 25. With the abolition of National Service for men in 1960, these young people had more freedom and fewer responsibilities than their parents’ generation. They rebelled against the limitations and restrictions of post-War society. In short, they wanted to shake things up…

Added to this, Londoners had more disposable income than ever before – and were looking for ways to spend it. Nationally, weekly earnings in the ‘60s outstripped the cost of living by a staggering 183%: in London, where earnings were generally higher than the national average, the figure was probably even greater.

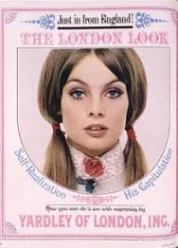

This heady combination of affluence and youth led to a flourishing of music, fashion, design and anything else that would banish the post-War gloom. Fashion boutiques sprang up willy-nilly. Men flocked to Carnaby St, near Soho, for the latest ‘Mod’ fashions. While women were lured to the King’s Rd, where Mary Quant’s radical mini skirts flew off the rails of her iconic store, Bazaar.

Even the most shocking or downright barmy fashions were popularised by models who, for the first time, became superstars. Jean Shrimpton was considered the symbol of Swinging London, while Twiggy was named The Face of 1966. Mary Quant herself was the undisputed queen of the group known as The Chelsea Set, a hard-partying, socially eclectic mix of largely idle ‘toffs’ and talented working-class movers and shakers.

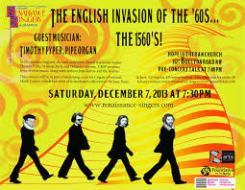

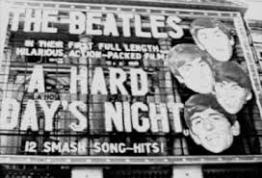

Music was also a huge part of London’s swing. While Liverpool had the Beatles, the London sound was a mix of bands who went on to worldwide success, including The Who, The Kinks, The Small Faces and The Rolling Stones. Their music was the mainstay of pirate radio stations like Radio Caroline and Radio Swinging England. Creative types of all kinds gravitated to the capital, from artists and writers to magazine publishers, photographers, advertisers, film-makers and product designers.

But not everything in London’s garden was rosy. Immigration was a political hot potato: by 1961, there were over 100,000 West Indians in London, and not everyone welcomed them with open arms. The biggest problem of all was a huge shortage of housing to replace bombed buildings and unfit slums and cope with a booming urban population. The badly-conceived solution – huge estates of tower blocks – and the social problems they created, changed the face of London for ever. By the 1970s, with industry declining and unemployment rising, Swinging London seemed a very dim and distant memory.

Introduction by Dominic Sandbrook

In 1965 My best friend Linda and I were walking barefoot along Tower Bridge when we came face to face with Harold WIlson, he smiled and walked on. We giggled, flabbergasted that he would acknowledge a couple of hippies.

A WALK ACROSS TOWER BRIDGE

“WHEN IN DOUBT DRINK TEA” Ana Christy

Review by Peter Aspden

Review by Peter Aspden