|

| ©Unknown |

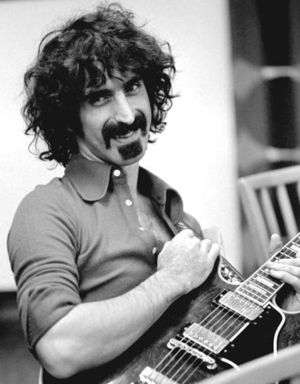

| Frank Zappa: Pro-war, authoritarian, and what else? |

“There’s something happening here

What it is ain’t exactly clear”

Join me now, if you have the time, as we take a stroll down memory lane to a time nearly four-and-a-half decades ago – a time when America last had uniformed ground troops fighting a sustained and bloody battle to impose, uhmm, ‘democracy’ on a sovereign nation.

It is the first week of August, 1964, and U.S. warships under the command of U.S. Navy Admiral George Stephen Morrison have allegedly come under attack while patrolling Vietnam’s Tonkin Gulf. This event, subsequently dubbed the ‘Tonkin Gulf Incident,’ will result in the immediate passing by the U.S. Congress of the obviously pre-drafted Tonkin Gulf Resolution, which will, in turn, quickly lead to America’s deep immersion into the bloody Vietnam quagmire. Before it is over, well over fifty thousand American bodies – along with literally millions of Southeast Asian bodies – will litter the battlefields of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia.

For the record, the Tonkin Gulf Incident appears to differ somewhat from other alleged provocations that have driven this country to war. This was not, as we have seen so many times before, a ‘false flag’ operation (which is to say, an operation that involves Uncle Sam attacking himself and then pointing an accusatory finger at someone else). It was also not, as we have also seen on more than one occasion, an attack that was quite deliberately provoked. No, what the Tonkin Gulf incident actually was, as it turns out, is an ‘attack’ that never took place at all. The entire incident, as has been all but officially acknowledged, was spun from whole cloth. (It is quite possible, however, that the intent was to provoke a defensive response, which could then be cast as an unprovoked attack on U.S ships. The ships in question were on an intelligence mission and were operating in a decidedly provocative manner. It is quite possible that when Vietnamese forces failed to respond as anticipated, Uncle Sam decided to just pretend as though they had.)

Nevertheless, by early February 1965, the U.S. will – without a declaration of war and with no valid reason to wage one – begin indiscriminately bombing North Vietnam. By March of that same year, the infamous “Operation Rolling Thunder” will have commenced. Over the course of the next three-and-a-half years, millions of tons of bombs, missiles, rockets, incendiary devices and chemical warfare agents will be dumped on the people of Vietnam in what can only be described as one of the worst crimes against humanity ever perpetrated on this planet.

Also in March of 1965, the first uniformed U.S. soldier will officially set foot on Vietnamese soil (although Special Forces units masquerading as ‘advisers’ and ‘trainers’ had been there for at least four years, and likely much longer). By April 1965, fully 25,000 uniformed American kids, most still teenagers barely out of high school, will be slogging through the rice paddies of Vietnam. By the end of the year, U.S. troop strength will have surged to 200,000.

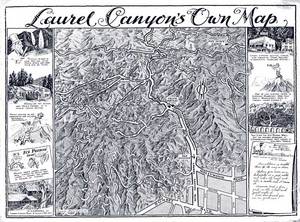

Meanwhile, elsewhere in the world in those early months of 1965, a new ‘scene’ is just beginning to take shape in the city of Los Angeles. In a geographically and socially isolated community known as Laurel Canyon – a heavily wooded, rustic, serene, yet vaguely ominous slice of LA nestled in the hills that separate the Los Angeles basin from the San Fernando Valley – musicians, singers and songwriters suddenly begin to gather as though summoned there by some unseen Pied Piper. Within months, the ‘hippie/flower child’ movement will be given birth there, along with the new style of music that will provide the soundtrack for the tumultuous second half of the 1960s.

An uncanny number of rock music superstars will emerge from Laurel Canyon beginning in the mid-1960s and carrying through the decade of the 1970s. The first to drop an album will be The Byrds, whose biggest star will prove to be David Crosby. The band’s debut effort, “Mr. Tambourine Man,” will be released on the Summer Solstice of 1965. It will quickly be followed by releases from the John Phillips-led Mamas and the Papas (“If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears,” January 1966), Love with Arthur Lee (“Love,” May 1966), Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention (“Freak Out,” June 1966), Buffalo Springfield, featuring Stephen Stills and Neil Young (“Buffalo Springfield,” October 1966), and The Doors (“The Doors,” January 1967).

One of the earliest on the Laurel Canyon/Sunset Strip scene is Jim Morrison, the enigmatic lead singer of The Doors. Jim will quickly become one of the most iconic, controversial, critically acclaimed, and influential figures to take up residence in Laurel Canyon. Curiously enough though, the self-proclaimed “Lizard King” has another claim to fame as well, albeit one that none of his numerous chroniclers will feel is of much relevance to his career and possible untimely death: he is the son, as it turns out, of the aforementioned Admiral George Stephen Morrison.

And so it is that, even while the father is actively conspiring to fabricate an incident that will be used to massively accelerate an illegal war, the son is positioning himself to become an icon of the ‘hippie’/anti-war crowd. Nothing unusual about that, I suppose. It is, you know, a small world and all that. And it is not as if Jim Morrison’s story is in any way unique.

During the early years of its heyday, Laurel Canyon’s father figure is the rather eccentric personality known as Frank Zappa. Though he and his various Mothers of Invention line-ups will never attain the commercial success of the band headed by the admiral’s son, Frank will be a hugely influential figure among his contemporaries. Ensconced in an abode dubbed the ‘Log Cabin’ – which sat right in the heart of Laurel Canyon, at the crossroads of Laurel Canyon Boulevard and Lookout Mountain Avenue – Zappa will play host to virtually every musician who passes through the canyon in the mid- to late-1960s. He will also discover and sign numerous acts to his various Laurel Canyon-based record labels. Many of these acts will be rather bizarre and somewhat obscure characters (think Captain Beefheart and Larry “Wild Man” Fischer), but some of them, such as psychedelic rocker cum shock-rocker Alice Cooper, will go on to superstardom.

Zappa, along with certain members of his sizable entourage (the ‘Log Cabin’ was run as an early commune, with numerous hangers-on occupying various rooms in the main house and the guest house, as well as in the peculiar caves and tunnels lacing the grounds of the home; far from the quaint homestead the name seems to imply, by the way, the ‘Log Cabin’ was a cavernous five-level home that featured a 2,000+ square-foot living room with three massive chandeliers and an enormous floor-to-ceiling stone fireplace), will also be instrumental in introducing the look and attitude that will define the ‘hippie’ counterculture (although the Zappa crew preferred the label ‘Freak’). Nevertheless, Zappa (born, curiously enough, on the Winter Solstice of 1940) never really made a secret of the fact that he had nothing but contempt for the ‘hippie’ culture that he helped create and that he surrounded himself with.

Given that Zappa was, by numerous accounts, a pro-war, rigidly authoritarian control-freak, it is perhaps not surprising that he would not feel a kinship with the youth movement that he helped nurture. And it is probably safe to say that Frank’s dad also had little regard for the youth culture of the 1960s, given that Francis Zappa was, in case you were wondering, a chemical warfare specialist assigned to – where else? – the Edgewood Arsenal. Edgewood is, of course, the longtime home of America’s chemical warfare program, as well as a facility frequently cited as being deeply enmeshed in MK-ULTRA operations. Curiously enough, Frank Zappa literally grew up at the Edgewood Arsenal, having lived the first seven years of his life in military housing on the grounds of the facility. The family later moved to Lancaster, California, near Edwards Air Force Base, where Francis Zappa continued to busy himself with doing classified work for the military/intelligence complex. His son, meanwhile, prepped himself to become an icon of the peace & love crowd. Again, nothing unusual about that, I suppose.

Zappa’s manager, by the way, is a shadowy character by the name of Herb Cohen, who had come out to L.A. from the Bronx with his brother Mutt just before the music and club scene began heating up. Cohen, a former U.S. Marine, had spent a few years traveling the world before his arrival on the Laurel Canyon scene. Those travels, curiously, had taken him to the Congo in 1961, at the very time that leftist Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba was being tortured and killed by our very own CIA. Not to worry though; according to one of Zappa’s biographers, Cohen wasn’t in the Congo on some kind of nefarious intelligence mission. No, he was there, believe it or not, to supply arms to Lumumba “in defiance of the CIA.” Because, you know, that is the kind of thing that globetrotting ex-Marines did in those days (as we’ll see soon enough when we take a look at another Laurel Canyon luminary).

Making up the other half of Laurel Canyon’s First Family is Frank’s wife, Gail Zappa, known formerly as Adelaide Sloatman. Gail hails from a long line of career Naval officers, including her father, who spent his life working on classified nuclear weapons research for the U.S. Navy. Gail herself had once worked as a secretary for the Office of Naval Research and Development (she also once told an interviewer that she had “heard voices all [her] life”). Many years before their nearly simultaneous arrival in Laurel Canyon, Gail had attended a Naval kindergarten with “Mr. Mojo Risin'” himself, Jim Morrison (it is claimed that, as children, Gail once hit Jim over the head with a hammer). The very same Jim Morrison had later attended the same Alexandria, Virginia high school as two other future Laurel Canyon luminaries – John Phillips and Cass Elliott.

“Papa” John Phillips, more so than probably any of the other illustrious residents of Laurel Canyon, will play a major role in spreading the emerging youth ‘counterculture’ across America. His contribution will be twofold: first, he will co-organize (along with Manson associate Terry Melcher) the famed Monterrey Pop Festival, which, through unprecedented media exposure, will give mainstream America its first real look at the music and fashions of the nascent ‘hippie’ movement. Second, Phillips will pen an insipid song known as “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair),” which will quickly rise to the top of the charts. Along with the Monterrey Pop Festival, the song will be instrumental in luring the disenfranchised (a preponderance of whom are underage runaways) to San Francisco to create the Haight-Asbury phenomenon and the famed 1967 “Summer of Love.”

Before arriving in Laurel Canyon and opening the doors of his home to the soon-to-be famous, the already famous, and the infamous (such as the aforementioned Charlie Manson, whose ‘Family’ also spent time at the Log Cabin and at the Laurel Canyon home of “Mama” Cass Elliot, which, in case you didn’t know, sat right across the street from the Laurel Canyon home of Abigail Folger and Voytek Frykowski, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves here), John Edmund Andrew Phillips was, shockingly enough, yet another child of the military/intelligence complex. The son of U.S. Marine Corp Captain Claude Andrew Phillips and a mother who claimed to have psychic and telekinetic powers, John attended a series of elite military prep schools in the Washington, D.C. area, culminating in an appointment to the prestigious U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis

After leaving Annapolis, John married Susie Adams, a direct descendant of ‘Founding Father’ John Adams. Susie’s father, James Adams, Jr., had been involved in what Susie described as “cloak-and-dagger stuff with the Air Force in Vienna,” or what we like to call covert intelligence operations. Susie herself would later find employment at the Pentagon, alongside John Phillip’s older sister, Rosie, who dutifully reported to work at the complex for nearly thirty years. John’s mother, ‘Dene’ Phillips, also worked for most of her life for the federal government in some unspecified capacity. And John’s older brother, Tommy, was a battle-scarred former U.S. Marine who found work as a cop on the Alexandria police force, albeit one with a disciplinary record for exhibiting a violent streak when dealing with people of color.

John Phillips, of course – though surrounded throughout his life by military/intelligence personnel – did not involve himself in such matters. Or so we are to believe. Before succeeding in his musical career, however, John did seem to find himself, quite innocently of course, in some rather unusual places. One such place was Havana, Cuba, where Phillips arrived at the very height of the Cuban Revolution. For the record, Phillips has claimed that he went to Havana as nothing more than a concerned private citizen, with the intention of – you’re going to love this one – “fighting for Castro.” Because, as I mentioned earlier, a lot of folks in those days traveled abroad to thwart CIA operations before taking up residence in Laurel Canyon and joining the ‘hippie’ generation. During the two weeks or so that the Cuban Missile Crisis played out, a few years after Castro took power, Phillips found himself cooling his heels in Jacksonville, Florida – alongside, coincidentally I’m sure, the Mayport Naval Station.

Anyway, let’s move on to yet another of Laurel Canyon’s earliest and brightest stars, Mr. Stephen Stills. Stills will have the distinction of being a founding member of two of Laurel Canyon’s most acclaimed and beloved bands: Buffalo Springfield, and, needless to say, Crosby, Stills & Nash. In addition, Stills will pen perhaps the first, and certainly one of the most enduring anthems of the 60s generation, “For What It’s Worth,” the opening lines of which appear at the top of this post (Stills’ follow-up single will be entitled “Bluebird,” which, coincidentally or not, happens to be the original codename assigned to the MK-ULTRA program).

Before his arrival in Laurel Canyon, Stephen Stills was (*yawn*) the product of yet another career military family. Raised partly in Texas, young Stephen spent large swaths of his childhood in El Salvador, Costa Rica, the Panama Canal Zone, and various other parts of Central America – alongside his father, who was, we can be fairly certain, helping to spread ‘democracy’ to the unwashed masses in that endearingly American way. As with the rest of our cast of characters, Stills was educated primarily at schools on military bases and at elite military academies. Among his contemporaries in Laurel Canyon, he was widely viewed as having an abrasive, authoritarian personality. Nothing unusual about any of that, of course, as we have already seen with the rest of our cast of characters.

There is, however, an even more curious aspect to the Stephen Stills story: Stephen will later tell anyone who will sit and listen that he had served time for Uncle Sam in the jungles of Vietnam. These tales will be universally dismissed by chroniclers of the era as nothing more than drug-induced delusions. Such a thing couldn’t possibly be true, it will be claimed, since Stills arrived on the Laurel Canyon scene at the very time that the first uniformed troops began shipping out and he remained in the public eye thereafter. And it will of course be quite true that Stephen Stills could not have served with uniformed ground troops in Vietnam, but what will be ignored is the undeniable fact that the U.S. had thousands of ‘advisers’ – which is to say, CIA/Special Forces operatives – operating in the country for a good many years before the arrival of the first official ground troops. What will also be ignored is that, given his background, his age, and the timeline of events, Stephen Stills not only could indeed have seen action in Vietnam, he would seem to have been a prime candidate for such an assignment. After which, of course, he could rather quickly become – stop me if you’ve heard this one before – an icon of the peace generation.

Another of those icons, and one of Laurel Canyon’s most flamboyant residents, is a young man by the name of David Crosby, founding member of the seminal Laurel Canyon band the Byrds, as well as, of course, Crosby, Stills & Nash. Crosby is, not surprisingly, the son of an Annapolis graduate and WWII military intelligence officer, Major Floyd Delafield Crosby. Like others in this story, Floyd Crosby spent much of his post-service time traveling the world. Those travels landed him in places like Haiti, where he paid a visit in 1927, when the country just happened to be, coincidentally of course, under military occupation by the U.S. Marines. One of the Marines doing that occupying was a guy that we met earlier by the name of Captain Claude Andrew Phillips.

But David Crosby is much more than just the son of Major Floyd Delafield Crosby. David Van Cortlandt Crosby, as it turns out, is a scion of the closely intertwined Van Cortlandt, Van Schuyler and Van Rensselaer families. And while you’re probably thinking, “the Van Who families?,” I can assure you that if you plug those names in over at Wikipedia, you can spend a pretty fair amount of time reading up on the power wielded by this clan for the last, oh, two-and-a-quarter centuries or so. Suffice it to say that the Crosby family tree includes a truly dizzying array of US senators and congressmen, state senators and assemblymen, governors, mayors, judges, Supreme Court justices, Revolutionary and Civil War generals, signers of the Declaration of Independence, and members of the Continental Congress. It also includes, I should hasten to add – for those of you with a taste for such things – more than a few high-ranking Masons. Stephen Van Rensselaer III, for example, reportedly served as Grand Master of Masons for New York. And if all that isn’t impressive enough, according to the New England Genealogical Society, David Van Cortlandt Crosby is also a direct descendant of ‘Founding Fathers’ and Federalist Papers’ authors Alexander Hamilton and John Jay.

If there is, as many believe, a network of elite families that has shaped national and world events for a very long time, then it is probably safe to say that David Crosby is a bloodline member of that clan (which may explain, come to think of it, why his semen seems to be in such demand in certain circles – because, if we’re being honest here, it certainly can’t be due to his looks or talent.) If America had royalty, then David Crosby would probably be a Duke, or a Prince, or something similar (I’m not really sure how that shit works). But other than that, he is just a normal, run-of-the-mill kind of guy who just happened to shine as one of Laurel Canyon’s brightest stars. And who, I guess I should add, has a real fondness for guns, especially handguns, which he has maintained a sizable collection of for his entire life. According to those closest to him, it is a rare occasion when Mr. Crosby is not packing heat (John Phillips also owned and sometimes carried handguns). And according to Crosby himself, he has, on at least one occasion, discharged a firearm in anger at another human being. All of which made him, of course, an obvious choice for the Flower Children to rally around.

Another shining star on the Laurel Canyon scene, just a few years later, will be singer-songwriter Jackson Browne, who is – are you getting as bored with this as I am? – the product of a career military family. Browne’s father was assigned to post-war ‘reconstruction’ work in Germany, which very likely means that he was in the employ of the OSS, precursor to the CIA. As readers of my “Understanding the F-Word” may recall, U.S. involvement in post-war reconstruction in Germany largely consisted of maintaining as much of the Nazi infrastructure as possible while shielding war criminals from capture and prosecution. Against that backdrop, Jackson Browne was born in a military hospital in Heidelberg, Germany. Some two decades later, he emerged as … oh, never mind.

Let’s talk instead about three other Laurel Canyon vocalists who will rise to dizzying heights of fame and fortune: Gerry Beckley, Dan Peek and Dewey Bunnell. Individually, these three names are probably unknown to virtually all readers; but collectively, as the band America, the three will score huge hits in the early ’70s with such songs as “Ventura Highway,” “A Horse With No Name,” and the Wizard of Oz-themed “The Tin Man.” I guess I probably don’t need to add here that all three of these lads were products of the military/intelligence community. Beckley’s dad was the commander of the now-defunct West Ruislip USAF base near London, England, a facility deeply immersed in intelligence operations. Bunnell’s and Peek’s fathers were both career Air Force officers serving under Beckley’s dad at West Ruislip, which is where the three boys first met.

We could also, I suppose, discuss Mike Nesmith of the Monkees and Cory Wells of Three Dog Night (two more hugely successful Laurel Canyon bands), who both arrived in LA not long after serving time with the U.S. Air Force. Nesmith also inherited a family fortune estimated at $25 million. Gram Parsons, who would briefly replace David Crosby in The Byrds before fronting The Flying Burrito Brothers, was the son of Major Cecil Ingram “Coon Dog” Connor II, a decorated military officer and bomber pilot who reportedly flew over 50 combat missions. Parsons was also an heir, on his mother’s side, to the formidable Snively family fortune. Said to be the wealthiest family in the exclusive enclave of Winter Haven, Florida, the Snively family was the proud owner of Snively Groves, Inc., which reportedly owned as much as 1/3 of all the citrus groves in the state of Florida.

And so it goes as one scrolls through the roster of Laurel Canyon superstars. What one finds, far more often than not, are the sons and daughters of the military/intelligence complex and the sons and daughters of extreme wealth and privilege – and oftentimes, you’ll find both rolled into one convenient package. Every once in a while, you will also stumble across a former child actor, like the aforementioned Brandon DeWilde, or Monkee Mickey Dolenz, or eccentric prodigy Van Dyke Parks. You might also encounter some former mental patients, such as James Taylor, who spent time in two different mental institutions in Massachusetts before hitting the Laurel Canyon scene, or Larry “Wild Man” Fischer, who was institutionalized repeatedly during his teen years, once for attacking his mother with a knife (an act that was gleefully mocked by Zappa on the cover of Fischer’s first album). Finally, you might find the offspring of an organized crime figure, like Warren Zevon, the son of William “Stumpy” Zevon, a lieutenant for infamous LA crimelord Mickey Cohen.

All these folks gathered nearly simultaneously along the narrow, winding roads of Laurel Canyon. They came from across the country – although the Washington, DC area was noticeably over-represented – as well as from Canada and England. They came even though, at the time, there was no music industry in Los Angeles. They came even though, at the time, there was no live music scene to speak of. They came even though, in retrospect, there was no discernable reason for them to do so.

It would, of course, make sense these days for an aspiring musician to venture out to Los Angeles. But in those days, the centers of the music universe were Nashville, Memphis and New York. It wasn’t the industry that drew the Laurel Canyon crowd, you see, but rather the Laurel Canyon crowd that transformed Los Angeles into the epicenter of the music industry. To what then do we attribute this unprecedented gathering of future musical superstars in the hills above Los Angeles? What was it that inspired them all to head out west? Perhaps Neil Young said it best when he told an interviewer that he couldn’t really say why he headed out to LA circa 1966; he and others “were just going like Lemmings.”

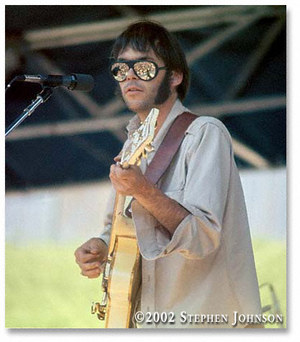

“He had this kind of music that nobody else was doing. I thought he really had something crazy, something great. He was like a living poet.”

|

| ©Steven Johnson |

[Today’s first trivia question: both of the above statements were made, on separate occasions, by a famous Laurel Canyon musician of the 1960s era. Both quotes were offered up in praise of another Laurel Canyon musician. Award yourself five points for correctly identifying the person who made the remarks, and five for identifying who the statements refer to. The answers are at the end of this post.]

In the first chapter of this saga, we met a sampling of some of the most successful and influential rock music superstars who emerged from Laurel Canyon during its glory days. But these were, alas, more than just musicians and singers and songwriters who had come together in the canyon; they were destined to become the spokesmen and de facto leaders of a generation of disaffected youth (as Carl Gottlieb noted in David Crosby’s co-written autobiography, “the unprecedented mass appeal of the new rock ‘n’ roll gave the singers a voice in public affairs.”) That, of course, makes it all the more curious that these icons were, to an overwhelming degree, the sons and daughters of the military/intelligence complex and the scions of families that have wielded vast wealth and power in this country for a very long time.

When I recently presented to a friend a truncated summary of the information contained in the first installment of this series, said friend opted to play the devil’s advocate by suggesting that there was nothing necessarily nefarious in the fact that so many of these icons of a past generation hailed from military/intelligence families. Perhaps, he suggested, they had embarked on their chosen careers as a form of rebellion against the values of their parents. And that, I suppose, might be true in a couple of cases. But what are we to conclude from the fact that such an astonishing number of these folks (along with their girlfriends, wives, managers, etc.) hail from a similar background? Are we to believe that the only kids from that era who had musical talent were the sons and daughters of Navy Admirals, chemical warfare engineers and Air Force intelligence officers? Or are they just the only ones who were signed to lucrative contracts and relentlessly promoted by their labels and the media?

If these artists were rebelling against, rather than subtly promoting, the values of their parents, then why didn’t they ever speak out against the folks they were allegedly rebelling against? Why did Jim Morrison never denounce, or even mention, his father’s key role in escalating one of America’s bloodiest illegal wars? And why did Frank Zappa never pen a song exploring the horrors of chemical warfare (though he did pen a charming little ditty entitled “The Ritual Dance of the Child-Killer”)? And which Mamas and Papas song was it that laid waste to the values and actions of John Phillip’s parents and in-laws? And in which interview, exactly, did David Crosby and Stephen Stills disown the family values that they were raised with?

In the coming weeks, we will take a much closer look at these folks, as well as at many of their contemporaries, as we endeavor to determine how and why the youth ‘counterculture’ of the 1960s was given birth. According to virtually all the accounts that I have read, this was essentially a spontaneous, organic response to the war in Southeast Asia and to the prevailing social conditions of the time. ‘Conspiracy theorists,’ of course, have frequently opined that what began as a legitimate movement was at some point co-opted and undermined by intelligence operations such as CoIntelPro. Entire books, for example, have been written examining how presumably virtuous musical artists were subjected to FBI harassment and/or whacked by the CIA.

Here we will, as you have no doubt already ascertained, take a decidedly different approach. The question that we will be tackling is a more deeply troubling one: “what if the musicians themselves (and various other leaders and founders of the ‘movement’) were every bit as much a part of the intelligence community as the people who were supposedly harassing them?” What if, in other words, the entire youth culture of the 1960s was created not as a grass-roots challenge to the status quo, but as a cynical exercise in discrediting and marginalizing the budding anti-war movement and creating a fake opposition that could be easily controlled and led astray? And what if the harassment these folks were subjected to was largely a stage-managed show designed to give the leaders of the counterculture some much-needed ‘street cred’? What if, in reality, they were pretty much all playing on the same team?

I should probably mention here that, contrary to popular opinion, the ‘hippie’/’flower child’ movement was not synonymous with the anti-war movement. As time passed, there was, to be sure, a fair amount of overlap between the two ‘movements.’ And the mass media outlets, as is their wont, did their very best to portray the flower-power generation as the torch-bearers of the anti-war movement – because, after all, a ragtag band of unwashed, drug-fueled long-hairs sporting flowers and peace symbols was far easier to marginalize than, say, a bunch of respected college professors and their concerned students. The reality, however, is that the anti-war movement was already well underway before the first aspiring ‘hippie’ arrived in Laurel Canyon. The first Vietnam War ‘teach-in’ was held on the campus of the University of Michigan in March of 1965. The first organized walk on Washington occurred just a few weeks later. Needless to say, there were no ‘hippies’ in attendance at either event. That ‘problem’ would soon be rectified. And the anti-war crowd – those who were serious about ending the bloodshed in Vietnam, anyway – would be none too appreciative.

As Barry Miles has written in his coffee-table book, Hippie, there were some hippies involved in anti-war protests, “particularly after the police riot in Chicago in 1968 when so many people got injured, but on the whole the movement activists looked on hippies with disdain.” Peter Coyote, narrating the documentary “Hippies” on The History Channel, added that “Some on the left even theorized that the hippies were the end result of a plot by the CIA to neutralize the anti-war movement with LSD, turning potential protestors into self-absorbed naval-gazers.” An exasperated Abbie Hoffman once described the scene as he remembered it thusly: “There were all these activists, you know, Berkeley radicals, White Panthers … all trying to stop the war and change things for the better. Then we got flooded with all these ‘flower children’ who were into drugs and sex. Where the hell did the hippies come from?!”

As it turns out, they came, initially at least, from a rather private, isolated, largely self-contained neighborhood in Los Angeles known as Laurel Canyon (in contrast to the other canyons slicing through the Hollywood Hills, Laurel Canyon has its own market, the semi-famous Laurel Canyon Country Store; its own deli and cleaners; its own elementary school, the Wonderland School; its own boutique shops and salons; and, in more recent years, its own celebrity reprogramming rehab facility named, as you may have guessed, the Wonderland Center. During its heyday, the canyon even had its own management company, Lookout Management, to handle the talent. At one time, it even had its own newspaper.)

One other thing that I should add here, before getting too far along with this series, is that this has not been an easy line of research for me to conduct, primarily because I have been, for as long as I can remember, a huge fan of 1960s music and culture. Though I was born in 1960 and therefore didn’t come of age, so to speak, until the 1970s, I have always felt as though I was ripped off by being denied the opportunity to experience firsthand the era that I was so obviously meant to inhabit. During my high school and college years, while my peers were mostly into faceless corporate rock (think Journey, Foreigner, Kansas, Boston, etc.) and, perhaps worse yet, the twin horrors of New Wave and Disco music, I was faithfully spinning my Hendrix, Joplin and Doors albums (which I still have, or rather my eldest daughter still has, in the original vinyl versions) while my color organ (remember those?) competed with my black light and strobe light. I grew my hair long until well past the age when it should have been sheared off. I may have even strung beads across the doorway to my room, but it is possible that I am confusing my life with that of Greg Brady, who, as we all remember, once converted his dad’s home office into a groovy bachelor pad.

Anyway … as I have probably mentioned previously on more than one occasion, one of the most difficult aspects of this journey that I have been on for the last decade or so has been watching so many of my former idols and mentors fall by the wayside as it became increasingly clear to me that people who I once thought were the good guys were, in reality, something entirely different than what they appear to be. The first to fall, naturally enough, were the establishment figures – the politicians who I once, quite foolishly, looked up to as people who were fighting the good fight, within the confines of the system, to bring about real change. Though it now pains me to admit this, there was a time when I admired the likes of (egads!) George McGovern and Jimmy Carter, as well as (oops, excuse me for a moment; I seem to have just thrown up in my mouth a little bit) California pols Tom Hayden and Jerry Brown. I even had high hopes, oh-so-many-years-ago, for (am I really admitting this in print?) aspiring First Man Bill Clinton.

Since I mentioned Jerry “Governor Moonbeam” Brown, by the way, I must now digress just a bit – and we all know how I hate it when that happens. But as luck would have it, Jerry Brown was, curiously enough, a longtime resident of a little place called Laurel Canyon. As readers of Programmed to Kill may recall, Brown lived on Wonderland Avenue, not too many doors down from 8763 Wonderland Avenue, the site of the infamous “Four on the Floor” murders, regarded by grizzled LA homicide detectives as the most bloody and brutal multiple murder in the city’s very bloody history (if you get a chance, by the way, check out “Wonderland” with Val Kilmer the next time it shows up on your cable listings; it is, by Hollywood standards, a reasonably accurate retelling of the crime, and a pretty decent film as well).

As it turns out, you see, the most bloody mass murder in LA’s history took place in one of the city’s most serene, pastoral and exclusive neighborhoods. And strangely enough, the case usually cited as the runner-up for the title of bloodiest crime scene – the murders of Stephen Parent, Sharon Tate, Jay Sebring, Voytek Frykowski and Abigail Folger at 10050 Cielo Drive in Benedict Canyon, just a couple miles to the west of Laurel Canyon – had deep ties to the Laurel Canyon scene as well.

As previously mentioned, victims Folger and Frykowski lived in Laurel Canyon, at 2774 Woodstock Road, in a rented home right across the road from a favored gathering spot for Laurel Canyon royalty. Many of the regular visitors to Cass Elliot’s home, including a number of shady drug dealers, were also regular visitors to the Folger/Frykowski home (Frykowski’s son, by the way, was stabbed to death on June 6, 1999, thirty years after his father met the same fate.) Victim Jay Sebring’s acclaimed hair salon sat right at the mouth of Laurel Canyon, just below the Sunset Strip, and it was Sebring, alas, who was credited with sculpting Jim Morrison’s famous mane. One of the investors in his Sebring International business venture was a Laurel Canyon luminary who I may have mentioned previously, Mr. John Phillips.

Sharon Tate was also well known in Laurel Canyon, where she was a frequent visitor to the homes of friends like John Phillips, Cass Elliott, and Abby Folger. And when she wasn’t in Laurel Canyon, many of the canyon regulars, both famous and infamous, made themselves at home in her place on Cielo Drive. Canyonite Van Dyke Parks, for example, dropped by for a visit on the very day of the murders. And Denny Doherty, the other “Papa” in The Mamas and the Papas, has claimed that he and John Phillips were invited to the Cielo Drive home on the night of the murders, but, as luck would have it, they never made it over. (Similarly, Chuck Negron of Three Dog Night, a regular visitor to the Wonderland death house, had set up a drug buy on the night of that mass murder, but he fell asleep and never made it over.)

Along with the victims, the alleged killers also lived in and/or were very much a part of the Laurel Canyon scene. Bobby “Cupid” Beausoleil, for example, lived in a Laurel Canyon apartment during the early months of 1969. Charles “Tex” Watson, who allegedly led the death squad responsible for the carnage at Cielo Drive, lived for a time in a home on – guess where? – Wonderland Avenue. During that time, curiously enough, Watson co-owned and worked in a wig shop in Beverly Hills, Crown Wig Creations, Ltd., that was located near the mouth of Benedict Canyon. Meanwhile, one of Jay Sebring’s primary claims-to-fame was his expertise in crafting men’s hairpieces, which he did in his shop near the mouth of Laurel Canyon. A typical day then in the late 1960s would find Watson crafting hairpieces for an upscale Hollywood clientele near Benedict Canyon, and then returning home to Laurel Canyon, while Sebring crafted hairpieces for an upscale Hollywood clientele near Laurel Canyon, and then returned home to Benedict Canyon. And then one crazy day, as we all know, one of them became a killer and the other his victim. But there’s nothing odd about that, I suppose, so let’s move on.

Oh, wait a minute … we can’t quite move on just yet, as I forgot to mention that Sebring’s Benedict Canyon home, at 9820 Easton Drive, was a rather infamous Hollywood death house that had once belonged to Jean Harlow and Paul Bern. The mismatched pair were wed on July 2, 1932, when Harlow, already a huge star of the silver screen, was just twenty-one years old. Just two months later, on September 5, Bern caught a bullet to the head in his wife’s bedroom. He was found sprawled naked in a pool of his own blood, his corpse drenched with his wife’s perfume. Upon discovering the body, Bern’s butler promptly contacted MGM’s head of security, Whitey Hendry, who in turn contacted Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg. All three men descended upon the Benedict Canyon home to, you know, tidy up a bit. A couple hours later, they decided to contact the LAPD. This scene would be repeated years later when Sebring’s friends would rush to the home to clean up before officers investigating the Tate murders arrived.

Bern’s death was, needless to say, written off as a suicide. His newlywed wife, strangely enough, was never called as a witness at the inquest. Bern’s other wife – which is to say, his common-law wife, Dorothy Millette – reportedly boarded a Sacramento riverboat on September 6, 1932, the day after Paul’s death. She was next seen floating belly-up in the Sacramento River. Her death, as would be expected, was also ruled a suicide. Less than five years later, Harlow herself dropped dead at the ripe old age of 26. At the time, authorities opted not to divulge the cause of death, though it was later claimed that bad kidneys had done her in. During her brief stay on this planet, Harlow had cycled through three turbulent marriages and yet still found time to serve as Godmother to Bugsy Siegel’s daughter, Millicent.

Though Bern’s was the most famous body to be hauled out of the Easton Drive house in a coroner’s bag, it certainly wasn’t the only one. Another man had reportedly committed suicide there as well, in some unspecified fashion. Yet another unfortunate soul drowned in the home’s pool. And a maid was once found swinging from the end of a rope. Her death, needless to say, was ruled a suicide as well. That’s a lot of blood for one home to absorb, but the house’s morbid history, though a turn-off to many prospective residents, was reportedly exactly what attracted Jay Sebring to the property. His murder would further darken the black cloud hanging over the home.

As Laurel Canyon chronicler Michael Walker has noted, LA’s two most notorious mass murders, one in August of 1969 and the other in July of 1981 (both involving five victims, though at Wonderland one of the five miraculously survived), provided rather morbid bookends for Laurel Canyon’s glory years. Walker though, like others who have chronicled that time and place, treats these brutal crimes as though they were unfortunate aberrations. The reality, however, is that the nine bodies recovered from Cielo Drive and Wonderland Avenue constitute just the tip of a very large, and very bloody, iceberg. To partially illustrate that point, here is today’s second trivia question: what do Diane Linkletter (daughter of famed entertainer Art Linkletter), legendary comedian Lenny Bruce, screen idol Sal Mineo, starlet Inger Stevens, and silent film star Ramon Novarro, all have in common?

If you answered that all were found dead in their homes, either in or at the mouth of Laurel Canyon, in the decade between 1966 and 1976, then award yourself five points. If you added that all five were, in all likelihood, murdered in their Laurel Canyon homes, then add five bonus points.

Only two of them, of course, are officially listed as murder victims (Mineo, who was stabbed to death outside his home at 8563 Holloway Drive on February 12, 1976, and Novarro, who was killed near the Country Store in a decidedly ritualistic fashion on the eve of Halloween, 1968). Inger Steven’s death in her home at 8000 Woodrow Wilson Drive, on April 30, 1970 (Walpurgisnacht on the occult calendar), was officially a suicide, though why she opted to propel herself through a decorative glass screen as part of that suicide remains a mystery. Perhaps she just wanted to leave behind a gruesome crime scene, and simple overdoses can be so, you know, bloodless and boring.

Diane Linkletter, as we all know, sailed out the window of her Shoreham Towers apartment because, in her LSD-addled state, she thought she could fly, or some such thing. We know this because Art himself told us that it was so, and because the story was retold throughout the 1970s as a cautionary tale about the dangers of drugs. What we weren’t told, however, is that Diane (born, curiously enough, on Halloween day, 1948) wasn’t alone when she plunged six stories to her death on the morning of October 4, 1969. Au contraire, she was with a gent by the name of Edward Durston, who, in a completely unexpected turn of events, accompanied actress Carol Wayne to Mexico some 15 years later. Carol, alas, perhaps weighed down by her enormous breasts, managed to drown in barely a foot of water, while Mr. Durston promptly disappeared. As would be expected, he was never questioned by authorities about Wayne’s curious death. After all, it is quite common for the same guy to be the sole witness to two separate ‘accidental’ deaths.

Art also neglected to mention, by the way, that just weeks before Diane’s curious death, another member of the Linkletter clan, Art’s son-in-law, John Zwyer, caught a bullet to the head in the backyard of his Hollywood Hills home. But that, of course, was an unconnected, uhmm, suicide, so don’t go thinking otherwise.

I’m not even going to discuss here the circumstances of Bruce’s death from acute morphine poisoning on August 3, 1966, because, to be perfectly honest, I don’t know too many people who don’t already assume that Lenny was whacked. I’ll just note here that his funeral was well-attended by the Laurel Canyon rock icons, and control over his unreleased material fell into the hands of a guy by the name of Frank Zappa. And another rather unsavory character named Phil Spector, whose crack team of studio musicians, dubbed The Wrecking Crew, were the actual musicians playing on many studio recordings by such bands as The Monkees, The Byrds, The Beach Boys, and The Mamas and the Papas.

To Be Continued …

(As for the trivia question, the person being praised, of course, was our old friend Chuck Manson. And the guy singing his praises was Mr. Neil Young.) “He was great, he was unreal – really, really good.”

“He had this kind of music that nobody else was doing. I thought he really had something crazy, something great. He was like a living poet.”

|

| ©Steven Johnson |

[Today’s first trivia question: both of the above statements were made, on separate occasions, by a famous Laurel Canyon musician of the 1960s era. Both quotes were offered up in praise of another Laurel Canyon musician. Award yourself five points for correctly identifying the person who made the remarks, and five for identifying who the statements refer to. The answers are at the end of this post.]

In the first chapter of this saga, we met a sampling of some of the most successful and influential rock music superstars who emerged from Laurel Canyon during its glory days. But these were, alas, more than just musicians and singers and songwriters who had come together in the canyon; they were destined to become the spokesmen and de facto leaders of a generation of disaffected youth (as Carl Gottlieb noted in David Crosby’s co-written autobiography, “the unprecedented mass appeal of the new rock ‘n’ roll gave the singers a voice in public affairs.”) That, of course, makes it all the more curious that these icons were, to an overwhelming degree, the sons and daughters of the military/intelligence complex and the scions of families that have wielded vast wealth and power in this country for a very long time.

When I recently presented to a friend a truncated summary of the information contained in the first installment of this series, said friend opted to play the devil’s advocate by suggesting that there was nothing necessarily nefarious in the fact that so many of these icons of a past generation hailed from military/intelligence families. Perhaps, he suggested, they had embarked on their chosen careers as a form of rebellion against the values of their parents. And that, I suppose, might be true in a couple of cases. But what are we to conclude from the fact that such an astonishing number of these folks (along with their girlfriends, wives, managers, etc.) hail from a similar background? Are we to believe that the only kids from that era who had musical talent were the sons and daughters of Navy Admirals, chemical warfare engineers and Air Force intelligence officers? Or are they just the only ones who were signed to lucrative contracts and relentlessly promoted by their labels and the media?

If these artists were rebelling against, rather than subtly promoting, the values of their parents, then why didn’t they ever speak out against the folks they were allegedly rebelling against? Why did Jim Morrison never denounce, or even mention, his father’s key role in escalating one of America’s bloodiest illegal wars? And why did Frank Zappa never pen a song exploring the horrors of chemical warfare (though he did pen a charming little ditty entitled “The Ritual Dance of the Child-Killer”)? And which Mamas and Papas song was it that laid waste to the values and actions of John Phillip’s parents and in-laws? And in which interview, exactly, did David Crosby and Stephen Stills disown the family values that they were raised with?

In the coming weeks, we will take a much closer look at these folks, as well as at many of their contemporaries, as we endeavor to determine how and why the youth ‘counterculture’ of the 1960s was given birth. According to virtually all the accounts that I have read, this was essentially a spontaneous, organic response to the war in Southeast Asia and to the prevailing social conditions of the time. ‘Conspiracy theorists,’ of course, have frequently opined that what began as a legitimate movement was at some point co-opted and undermined by intelligence operations such as CoIntelPro. Entire books, for example, have been written examining how presumably virtuous musical artists were subjected to FBI harassment and/or whacked by the CIA.

Here we will, as you have no doubt already ascertained, take a decidedly different approach. The question that we will be tackling is a more deeply troubling one: “what if the musicians themselves (and various other leaders and founders of the ‘movement’) were every bit as much a part of the intelligence community as the people who were supposedly harassing them?” What if, in other words, the entire youth culture of the 1960s was created not as a grass-roots challenge to the status quo, but as a cynical exercise in discrediting and marginalizing the budding anti-war movement and creating a fake opposition that could be easily controlled and led astray? And what if the harassment these folks were subjected to was largely a stage-managed show designed to give the leaders of the counterculture some much-needed ‘street cred’? What if, in reality, they were pretty much all playing on the same team?

I should probably mention here that, contrary to popular opinion, the ‘hippie’/’flower child’ movement was not synonymous with the anti-war movement. As time passed, there was, to be sure, a fair amount of overlap between the two ‘movements.’ And the mass media outlets, as is their wont, did their very best to portray the flower-power generation as the torch-bearers of the anti-war movement – because, after all, a ragtag band of unwashed, drug-fueled long-hairs sporting flowers and peace symbols was far easier to marginalize than, say, a bunch of respected college professors and their concerned students. The reality, however, is that the anti-war movement was already well underway before the first aspiring ‘hippie’ arrived in Laurel Canyon. The first Vietnam War ‘teach-in’ was held on the campus of the University of Michigan in March of 1965. The first organized walk on Washington occurred just a few weeks later. Needless to say, there were no ‘hippies’ in attendance at either event. That ‘problem’ would soon be rectified. And the anti-war crowd – those who were serious about ending the bloodshed in Vietnam, anyway – would be none too appreciative.

As Barry Miles has written in his coffee-table book, Hippie, there were some hippies involved in anti-war protests, “particularly after the police riot in Chicago in 1968 when so many people got injured, but on the whole the movement activists looked on hippies with disdain.” Peter Coyote, narrating the documentary “Hippies” on The History Channel, added that “Some on the left even theorized that the hippies were the end result of a plot by the CIA to neutralize the anti-war movement with LSD, turning potential protestors into self-absorbed naval-gazers.” An exasperated Abbie Hoffman once described the scene as he remembered it thusly: “There were all these activists, you know, Berkeley radicals, White Panthers … all trying to stop the war and change things for the better. Then we got flooded with all these ‘flower children’ who were into drugs and sex. Where the hell did the hippies come from?!”

As it turns out, they came, initially at least, from a rather private, isolated, largely self-contained neighborhood in Los Angeles known as Laurel Canyon (in contrast to the other canyons slicing through the Hollywood Hills, Laurel Canyon has its own market, the semi-famous Laurel Canyon Country Store; its own deli and cleaners; its own elementary school, the Wonderland School; its own boutique shops and salons; and, in more recent years, its own celebrity reprogramming rehab facility named, as you may have guessed, the Wonderland Center. During its heyday, the canyon even had its own management company, Lookout Management, to handle the talent. At one time, it even had its own newspaper.)

One other thing that I should add here, before getting too far along with this series, is that this has not been an easy line of research for me to conduct, primarily because I have been, for as long as I can remember, a huge fan of 1960s music and culture. Though I was born in 1960 and therefore didn’t come of age, so to speak, until the 1970s, I have always felt as though I was ripped off by being denied the opportunity to experience firsthand the era that I was so obviously meant to inhabit. During my high school and college years, while my peers were mostly into faceless corporate rock (think Journey, Foreigner, Kansas, Boston, etc.) and, perhaps worse yet, the twin horrors of New Wave and Disco music, I was faithfully spinning my Hendrix, Joplin and Doors albums (which I still have, or rather my eldest daughter still has, in the original vinyl versions) while my color organ (remember those?) competed with my black light and strobe light. I grew my hair long until well past the age when it should have been sheared off. I may have even strung beads across the doorway to my room, but it is possible that I am confusing my life with that of Greg Brady, who, as we all remember, once converted his dad’s home office into a groovy bachelor pad.

Anyway … as I have probably mentioned previously on more than one occasion, one of the most difficult aspects of this journey that I have been on for the last decade or so has been watching so many of my former idols and mentors fall by the wayside as it became increasingly clear to me that people who I once thought were the good guys were, in reality, something entirely different than what they appear to be. The first to fall, naturally enough, were the establishment figures – the politicians who I once, quite foolishly, looked up to as people who were fighting the good fight, within the confines of the system, to bring about real change. Though it now pains me to admit this, there was a time when I admired the likes of (egads!) George McGovern and Jimmy Carter, as well as (oops, excuse me for a moment; I seem to have just thrown up in my mouth a little bit) California pols Tom Hayden and Jerry Brown. I even had high hopes, oh-so-many-years-ago, for (am I really admitting this in print?) aspiring First Man Bill Clinton.

Since I mentioned Jerry “Governor Moonbeam” Brown, by the way, I must now digress just a bit – and we all know how I hate it when that happens. But as luck would have it, Jerry Brown was, curiously enough, a longtime resident of a little place called Laurel Canyon. As readers of Programmed to Kill may recall, Brown lived on Wonderland Avenue, not too many doors down from 8763 Wonderland Avenue, the site of the infamous “Four on the Floor” murders, regarded by grizzled LA homicide detectives as the most bloody and brutal multiple murder in the city’s very bloody history (if you get a chance, by the way, check out “Wonderland” with Val Kilmer the next time it shows up on your cable listings; it is, by Hollywood standards, a reasonably accurate retelling of the crime, and a pretty decent film as well).

As it turns out, you see, the most bloody mass murder in LA’s history took place in one of the city’s most serene, pastoral and exclusive neighborhoods. And strangely enough, the case usually cited as the runner-up for the title of bloodiest crime scene – the murders of Stephen Parent, Sharon Tate, Jay Sebring, Voytek Frykowski and Abigail Folger at 10050 Cielo Drive in Benedict Canyon, just a couple miles to the west of Laurel Canyon – had deep ties to the Laurel Canyon scene as well.

As previously mentioned, victims Folger and Frykowski lived in Laurel Canyon, at 2774 Woodstock Road, in a rented home right across the road from a favored gathering spot for Laurel Canyon royalty. Many of the regular visitors to Cass Elliot’s home, including a number of shady drug dealers, were also regular visitors to the Folger/Frykowski home (Frykowski’s son, by the way, was stabbed to death on June 6, 1999, thirty years after his father met the same fate.) Victim Jay Sebring’s acclaimed hair salon sat right at the mouth of Laurel Canyon, just below the Sunset Strip, and it was Sebring, alas, who was credited with sculpting Jim Morrison’s famous mane. One of the investors in his Sebring International business venture was a Laurel Canyon luminary who I may have mentioned previously, Mr. John Phillips.

Sharon Tate was also well known in Laurel Canyon, where she was a frequent visitor to the homes of friends like John Phillips, Cass Elliott, and Abby Folger. And when she wasn’t in Laurel Canyon, many of the canyon regulars, both famous and infamous, made themselves at home in her place on Cielo Drive. Canyonite Van Dyke Parks, for example, dropped by for a visit on the very day of the murders. And Denny Doherty, the other “Papa” in The Mamas and the Papas, has claimed that he and John Phillips were invited to the Cielo Drive home on the night of the murders, but, as luck would have it, they never made it over. (Similarly, Chuck Negron of Three Dog Night, a regular visitor to the Wonderland death house, had set up a drug buy on the night of that mass murder, but he fell asleep and never made it over.)

Along with the victims, the alleged killers also lived in and/or were very much a part of the Laurel Canyon scene. Bobby “Cupid” Beausoleil, for example, lived in a Laurel Canyon apartment during the early months of 1969. Charles “Tex” Watson, who allegedly led the death squad responsible for the carnage at Cielo Drive, lived for a time in a home on – guess where? – Wonderland Avenue. During that time, curiously enough, Watson co-owned and worked in a wig shop in Beverly Hills, Crown Wig Creations, Ltd., that was located near the mouth of Benedict Canyon. Meanwhile, one of Jay Sebring’s primary claims-to-fame was his expertise in crafting men’s hairpieces, which he did in his shop near the mouth of Laurel Canyon. A typical day then in the late 1960s would find Watson crafting hairpieces for an upscale Hollywood clientele near Benedict Canyon, and then returning home to Laurel Canyon, while Sebring crafted hairpieces for an upscale Hollywood clientele near Laurel Canyon, and then returned home to Benedict Canyon. And then one crazy day, as we all know, one of them became a killer and the other his victim. But there’s nothing odd about that, I suppose, so let’s move on.

Oh, wait a minute … we can’t quite move on just yet, as I forgot to mention that Sebring’s Benedict Canyon home, at 9820 Easton Drive, was a rather infamous Hollywood death house that had once belonged to Jean Harlow and Paul Bern. The mismatched pair were wed on July 2, 1932, when Harlow, already a huge star of the silver screen, was just twenty-one years old. Just two months later, on September 5, Bern caught a bullet to the head in his wife’s bedroom. He was found sprawled naked in a pool of his own blood, his corpse drenched with his wife’s perfume. Upon discovering the body, Bern’s butler promptly contacted MGM’s head of security, Whitey Hendry, who in turn contacted Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg. All three men descended upon the Benedict Canyon home to, you know, tidy up a bit. A couple hours later, they decided to contact the LAPD. This scene would be repeated years later when Sebring’s friends would rush to the home to clean up before officers investigating the Tate murders arrived.

Bern’s death was, needless to say, written off as a suicide. His newlywed wife, strangely enough, was never called as a witness at the inquest. Bern’s other wife – which is to say, his common-law wife, Dorothy Millette – reportedly boarded a Sacramento riverboat on September 6, 1932, the day after Paul’s death. She was next seen floating belly-up in the Sacramento River. Her death, as would be expected, was also ruled a suicide. Less than five years later, Harlow herself dropped dead at the ripe old age of 26. At the time, authorities opted not to divulge the cause of death, though it was later claimed that bad kidneys had done her in. During her brief stay on this planet, Harlow had cycled through three turbulent marriages and yet still found time to serve as Godmother to Bugsy Siegel’s daughter, Millicent.

Though Bern’s was the most famous body to be hauled out of the Easton Drive house in a coroner’s bag, it certainly wasn’t the only one. Another man had reportedly committed suicide there as well, in some unspecified fashion. Yet another unfortunate soul drowned in the home’s pool. And a maid was once found swinging from the end of a rope. Her death, needless to say, was ruled a suicide as well. That’s a lot of blood for one home to absorb, but the house’s morbid history, though a turn-off to many prospective residents, was reportedly exactly what attracted Jay Sebring to the property. His murder would further darken the black cloud hanging over the home.

As Laurel Canyon chronicler Michael Walker has noted, LA’s two most notorious mass murders, one in August of 1969 and the other in July of 1981 (both involving five victims, though at Wonderland one of the five miraculously survived), provided rather morbid bookends for Laurel Canyon’s glory years. Walker though, like others who have chronicled that time and place, treats these brutal crimes as though they were unfortunate aberrations. The reality, however, is that the nine bodies recovered from Cielo Drive and Wonderland Avenue constitute just the tip of a very large, and very bloody, iceberg. To partially illustrate that point, here is today’s second trivia question: what do Diane Linkletter (daughter of famed entertainer Art Linkletter), legendary comedian Lenny Bruce, screen idol Sal Mineo, starlet Inger Stevens, and silent film star Ramon Novarro, all have in common?

If you answered that all were found dead in their homes, either in or at the mouth of Laurel Canyon, in the decade between 1966 and 1976, then award yourself five points. If you added that all five were, in all likelihood, murdered in their Laurel Canyon homes, then add five bonus points.

Only two of them, of course, are officially listed as murder victims (Mineo, who was stabbed to death outside his home at 8563 Holloway Drive on February 12, 1976, and Novarro, who was killed near the Country Store in a decidedly ritualistic fashion on the eve of Halloween, 1968). Inger Steven’s death in her home at 8000 Woodrow Wilson Drive, on April 30, 1970 (Walpurgisnacht on the occult calendar), was officially a suicide, though why she opted to propel herself through a decorative glass screen as part of that suicide remains a mystery. Perhaps she just wanted to leave behind a gruesome crime scene, and simple overdoses can be so, you know, bloodless and boring.

Diane Linkletter, as we all know, sailed out the window of her Shoreham Towers apartment because, in her LSD-addled state, she thought she could fly, or some such thing. We know this because Art himself told us that it was so, and because the story was retold throughout the 1970s as a cautionary tale about the dangers of drugs. What we weren’t told, however, is that Diane (born, curiously enough, on Halloween day, 1948) wasn’t alone when she plunged six stories to her death on the morning of October 4, 1969. Au contraire, she was with a gent by the name of Edward Durston, who, in a completely unexpected turn of events, accompanied actress Carol Wayne to Mexico some 15 years later. Carol, alas, perhaps weighed down by her enormous breasts, managed to drown in barely a foot of water, while Mr. Durston promptly disappeared. As would be expected, he was never questioned by authorities about Wayne’s curious death. After all, it is quite common for the same guy to be the sole witness to two separate ‘accidental’ deaths.

Art also neglected to mention, by the way, that just weeks before Diane’s curious death, another member of the Linkletter clan, Art’s son-in-law, John Zwyer, caught a bullet to the head in the backyard of his Hollywood Hills home. But that, of course, was an unconnected, uhmm, suicide, so don’t go thinking otherwise.

I’m not even going to discuss here the circumstances of Bruce’s death from acute morphine poisoning on August 3, 1966, because, to be perfectly honest, I don’t know too many people who don’t already assume that Lenny was whacked. I’ll just note here that his funeral was well-attended by the Laurel Canyon rock icons, and control over his unreleased material fell into the hands of a guy by the name of Frank Zappa. And another rather unsavory character named Phil Spector, whose crack team of studio musicians, dubbed The Wrecking Crew, were the actual musicians playing on many studio recordings by such bands as The Monkees, The Byrds, The Beach Boys, and The Mamas and the Papas.

(As for the trivia question, the person being praised, of course, was our old friend Chuck Manson. And the guy singing his praises was Mr. Neil Young.)

* * * * * * * * * *

Before signing off, I need to make a couple of quick announcements for those of you who find yourselves thinking, “You know, I really need a little more Dave in my life. Reading the posts and the books is fine, I suppose, but I wish I could have a little something more.” If you fall into that category (and can’t afford professional counseling), then I have great news for you: mere days from now, on May 20, the DVD release of “National Treasure: Book of Secrets” will be available at a video store near you. And better yet, I have been awarded a regular monthly spot on the Meria Heller (www.meria.net) radio program, the first installment of which aired on April 20 (she picked the date, by the way, though it did seem perversely appropriate). Stay tuned to Meria’s website for upcoming show schedules.

“I mean, fuck, he auditioned for Neil [Young] for fuck’s sake.”

Graham Nash, explaining to author Michael Walker how close Charlie Manson was to the Laurel Canyon scene.

|

| ©Geffen |

During the ten-year period during which Bruce, Novarro, Mineo, Linkletter, Stevens, Tate, Sebring, Frykowski and Folger all turned up dead, a whole lot of other people connected to Laurel Canyon did as well, often under very questionable circumstances. The list includes, but is certainly not limited to, all of the following names:

* Marina Elizabeth Habe, whose body was carved up and tossed into the heavy brush along Mulholland Drive, just west of Bowmont Drive, on December 30, 1968. Habe, just seventeen at the time of her death, was the daughter of Hans Habe, who emigrated to the U.S. from fascist Austria circa 1940. Shortly thereafter, he married a General Foods heiress and began studying psychological warfare at the Military Intelligence Training Center. After completing his training, he put his psychological warfare skills to use by creating 18 newspapers in occupied Germany – under the direction, no doubt, of the OSS.

* Christine Hinton, who was killed in a head-on collision on September 30, 1969. At the time, Hinton was a girlfriend of David Crosby and the founder and head of The Byrd’s fan club. She was also the daughter of a career Army officer stationed at the notorious Presidio military base in San Francisco. Another of Crosby’s girlfriends from that same era was Shelley Roecker, who grew up on the Hamilton Air Force Base in Marin County.

* Jane Doe #59, found dumped into the heavy undergrowth of Laurel Canyon in November 1969, within sight of where Habe had been dumped less than a year earlier. The teenage girl, who was never identified, had been stabbed 157 times in the chest and throat.

* Alan “Blind Owl” Wilson, singer, songwriter and guitarist for the Laurel Canyon blues-rock band, Canned Heat, was found dead in his Topanga Canyon home on September 3, 1970. His death was written off as a suicide/OD. Wilson had moved to Topanga Canyon after the band’s Laurel Canyon home – on Lookout Mountain Avenue, next door to Joni Mitchell and Graham Nash’s home – burned to the ground. “Blind Owl” was just twenty-seven years old at the time of his death. A little more than a decade later, Wilson’s former bandmate, Bob “The Bear” Hite, who had once acknowledged in an interview that he had partied in the canyons with various members of the Manson Family, died of a heart attack at the ripe old age of 36.

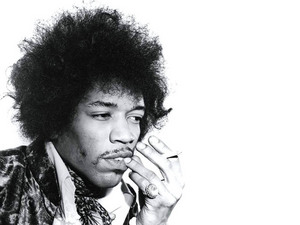

* Jimi Hendrix, who reportedly briefly occupied the sprawling mansion just north of the Log Cabin after he moved to LA in 1968, died in London under seriously questionable circumstances on September 18, 1970. Though he rarely spoke of it, Jimi had served a stint in the U.S. Army with the 101st Airborne Division at Fort Campbell. His official records indicate that he was forced into the service by the courts and then released after just one year when he purportedly proved to be a poor soldier. One wonders though why he was assigned to such an elite division if he was indeed such a failure. One also wonders why he wasn’t subjected to disciplinary measures rather than being handed a free pass out of his ostensibly court-ordered service. In any event, Jimi himself once told reporters that he was given a medical discharge after breaking an ankle during a parachute jump. And one biographer has claimed that Jimi faked being gay to earn an early release. The truth, alas, remains rather elusive. At the time of Jimi’s death, the first person called by his girlfriend – Monika Danneman, who was the last to see Hendrix alive – was Eric Burden of the Animals. Two years earlier, Burden had relocated to LA and taken over ringmaster duties from Frank Zappa after Zappa had vacated the Log Cabin and moved into a less high-profile Laurel Canyon home. Within a year of Jimi’s death, an underage prostitute named Devon Wilson who had been with Jimi the day before his death, plunged from an eighth-floor window of New York’s Chelsea Hotel. On March 5, 1973, a shadowy character named Michael Jeffery, who had managed both Hendrix and Burden, was killed in a mid-air plane collision. Jeffery was known to openly boast of having organized crime connections and of working for the CIA. After Jimi’s death, it was discovered that Jeffery had been funneling most of Hendrix’s gross earnings into offshore accounts in the Bahamas linked to international drug trafficking. Years later, on April 5, 1996, Danneman, the daughter of a wealthy German industrialist, was found dead near her home in a fume-filled Mercedes.

* Jim Morrison, who for a time lived in a home on Rothdell Trail, behind the Laurel Canyon Country Store, may or may not have died in Paris on July 3, 1971. The events of that day remain shrouded in mystery and rumor, and the details of the story, such as they are, have changed over the years. What is known is that, on that very same day, Admiral George Stephen Morrison delivered the keynote speech at a decommissioning ceremony for the aircraft carrier USS Bon Homme Richard, from where, seven years earlier, he had helped choreograph the Tonkin Gulf Incident. A few years after Jim’s death, his common-law wife, Pamela Courson, dropped dead as well, officially of a heroin overdose. Like Hendrix, Morrison had been an avid student of the occult, with a particular fondness for the work of Aleister Crowley. According to super-groupie Pamela DesBarres, he had also “read all he could about incest and sadism.” Also like Hendrix, Morrison was just twenty-seven at the time of his (possible) death.

* Brandon DeWilde, a good friend of David Crosby and Gram Parsons, was killed in a freak accident in Colorado on July 6, 1972, when his van plowed under a flatbed truck. In the 1950s, DeWilde had been an in-demand child actor since the age of eight. He had appeared on screen with some of the biggest names in Hollywood, including Alan Ladd, Lee Marvin, Paul Newman, John Wayne, Kirk Douglas and Henry Fonda. Around 1965, DeWilde fell in with Hollywood’s ‘Young Turks,’ through whom he met and befriended Crosby, Parsons, and various other members of the Laurel Canyon Club. DeWilde was just thirty at the time of his death.

* Christine Frka, a former governess for Moon Unit Zappa and the Zappa family’s former housekeeper at the Log Cabin, died on November 5, 1972 of an alleged drug overdose, though friends suspected foul play. As “Miss Christine,” Frka had been a member of the Zappa-created GTOs, a musical act, of sorts, composed entirely of very young groupies. She was also the inspiration for the song, “Christine’s Tune: Devil in Disguise” by Gram Parson’s Flying Burrito Brothers. Frka was probably in her early twenties when she died, possibly even younger.

* Danny Whitten, a guitarist/vocalist/songwriter with Neil Young’s sometime band, Crazy Horse, died of an overdose on November 18, 1972. According to rock ‘n’ roll legend, Whitten had been fired by Young earlier that day during rehearsals in San Francisco. Young and Jack Nietzsche, Phil Spector’s former top assistant, had given Whitten $50 and put him on a plane back to LA. Within hours, he was dead. Whitten was just twenty-nine.

* Bruce Berry, a roadie for Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, died of a heroin overdose in June 1973. Berry had just flown out to Maui to deliver a shipment of cocaine to Stephen Stills, and was promptly sent back to LA by Crosby and Nash. Berry was a brother of Jan Berry, of Jan and Dean. (Dean Torrence, the “Dean” of Jan and Dean, had played a part in the fake kidnapping of Frank Sinatra, Jr., just after the JFK assassination. The staged event was a particularly lame effort to divert attention away from the questions that were cropping up, after the initial shock had passed, about the events in Dealey Plaza.)

* Clarence White, a guitarist who had played with The Byrds, was run over by a drunk driver and killed on July 14, 1973. White had grown up near Lancaster, not far from where Frank Zappa spent his teen years. At least one member of White’s immediate family was employed at Edwards Air Force Base. The driver who killed young Clarence, just twenty-nine years old at the time of his death, was given a one-year suspended sentence and served no time.

* Gram Parsons, formerly with the International Submarine Band, The Byrds and the Flying Burrito Brothers, allegedly overdosed on a speedball at the Joshua Tree Inn on September 19, 1973. Just two months before his death, Parson’s Topanga Canyon home had burnt to the ground. After his death, his body was stolen from LAX by the Burrito’s road manager, Phil Kaufman, and then taken back out to Joshua Tree and ritually burned on the autumnal equinox (Kaufman had been a prison buddy of Charlie Manson’s at Terminal Island; when Phil was released from Terminal Island in March of 1968, he quickly reunited with his old pal, who had been released a year earlier.) By the time of Gram’s death, his family had already experienced its share of questionable deaths. Just before Christmas, 1958, Parson’s father had sent Gram, along with his mother and sister, off to stay with family in Florida. The next day, just after the winter solstice, “Coon Dog” caught a bullet to the head. His death was recorded as a suicide and it was claimed that he had sent his family away to spare them as much pain as possible. It seems just as likely, however, that “Coon Dog” knew his days were numbered and wanted to get his family out of the line of fire. The next year, 1959, Gram’s mother married again, to Robert Ellis Parsons, who adopted Gram and his sister Avis. Six years later, in June of 1965, Gram’s mother died the day after a sudden illness landed her in the hospital. According to witnesses, she died “almost immediately” after a visit from her husband, Robert Parsons. Many of those close to the situation believed that Parsons had a hand in her death (very shortly thereafter, Robert Parsons married his stepdaughter’s teenage babysitter). Following his mother’s death, Parsons briefly attended Harvard University, and then launched his music career with the formation of the International Submarine Band, which quickly found its way to – where else? – Laurel Canyon. Gram’s death in 1973 at the age of 26 left his younger sister Avis as the sole surviving member of the family. She was killed in 1993, reportedly in a boating accident, at the age of 43.

* “Mama” Cass Elliot, the “Earth Mother” of Laurel Canyon whose circle of friends included musicians, Mansonites, young Hollywood stars, the wealthy son of a State Department official, singer/songwriters, assorted drug dealers, and some particularly unsavory characters the LAPD once described as “some kind of hit squad,” died in the London home of Harry Nilsson on July 29, 1974 (Nilsson had been a frequent drinking buddy of John Lennon in Laurel Canyon and on the Sunset Strip). At thirty-two, Cass had lived a long and productive life, by Laurel Canyon standards. Four years later, in the very same room of the very same London flat, still owned by Harry Nilsson, Keith Moon of The Who also died at thirty-two (on September 7, 1978). Though initial press reports held that Cass had choked to death on a ham sandwich, the official cause of death was listed as heart failure. Her actual cause of death could likely be filed under “knowing where too many of the bodies were buried.” Moon reportedly died from a massive overdose of a drug used to treat alcohol withdrawal.

* Amy Gossage, Graham Nash’s girlfriend at the time, was murdered in her San Francisco home on February 13, 1975. Just twenty years old at the time, she had been stabbed nearly fifty times and was bludgeoned beyond recognition. Amy’s father, a famed advertising/PR executive, had died of leukemia in 1969. Not long after, her half-sister had been killed in a car crash. In May of 1974, her mother, the daughter of a wealthy banking family, died as well, reportedly of cirrhosis of the liver. That left just Amy, age 19, and her brother Eben, age 20, both of whom reportedly had serious drug dependencies. Amy’s brutal murder, cleverly enough, was pinned on Eben. Police had conveniently found bloodstained clothes, along with a hammer and scissors, sitting on the porch of Eben’s apartment, looking very much as though it had been planted. A friend of Eben’s would later remark, perhaps quite tellingly, “If Eben did kill her, I’m convinced he doesn’t know he did it.”

* Tim Buckley, a singer/songwriter signed to Frank Zappa’s record label and managed by Herb Cohen, died of a reported overdose on June 29, 1975. Buckley had once appeared on an episode of The Monkees, and, like Monkee Peter Tork (and so many others in this story), he hailed from Washington, DC. Buckley was just twenty-eight at the time of his death. His son, Jeff Buckley, also an accomplished musician, managed to remain on this planet two years longer than his dad did; he was thirty when he died in a bizarre drowning incident on May 29, 1997.