For a few years in the 1960s, London was the world capital of cool. When Time magazine dedicated its 15 April 1966 issue to London: the Swinging City, it cemented the association between London and all things hip and fashionable that had been growing in the popular imagination throughout the decade.

ENGLAND IN THE 60’S ARTICLE 2

London’s remarkable metamorphosis from a gloomy, grimy post-War capital into a bright, shining epicentre of style was largely down to two factors: youth and money. The baby boom of the 1950s meant that the urban population was younger than it had been since Roman times. By the mid-60s, 40% of the population at large was under 25. With the abolition of National Service for men in 1960, these young people had more freedom and fewer responsibilities than their parents’ generation. They rebelled against the limitations and restrictions of post-War society. In short, they wanted to shake things up…

Added to this, Londoners had more disposable income than ever before – and were looking for ways to spend it. Nationally, weekly earnings in the ‘60s outstripped the cost of living by a staggering 183%: in London, where earnings were generally higher than the national average, the figure was probably even greater.

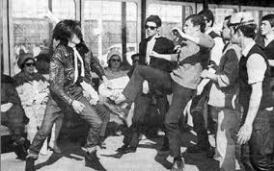

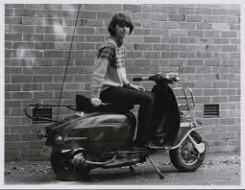

This heady combination of affluence and youth led to a flourishing of music, fashion, design and anything else that would banish the post-War gloom. Fashion boutiques sprang up willy-nilly. Men flocked to Carnaby St, near Soho, for the latest ‘Mod’ fashions. While women were lured to the King’s Rd, where Mary Quant’s radical mini skirts flew off the rails of her iconic store, Bazaar.

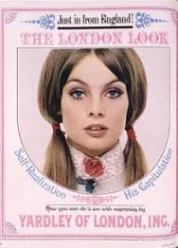

Even the most shocking or downright barmy fashions were popularised by models who, for the first time, became superstars. Jean Shrimpton was considered the symbol of Swinging London, while Twiggy was named The Face of 1966. Mary Quant herself was the undisputed queen of the group known as The Chelsea Set, a hard-partying, socially eclectic mix of largely idle ‘toffs’ and talented working-class movers and shakers.

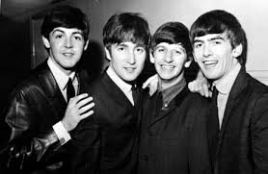

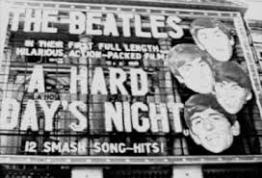

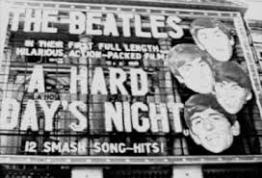

Music was also a huge part of London’s swing. While Liverpool had the Beatles, the London sound was a mix of bands who went on to worldwide success, including The Who, The Kinks, The Small Faces and The Rolling Stones. Their music was the mainstay of pirate radio stations like Radio Caroline and Radio Swinging England. Creative types of all kinds gravitated to the capital, from artists and writers to magazine publishers, photographers, advertisers, film-makers and product designers.

But not everything in London’s garden was rosy. Immigration was a political hot potato: by 1961, there were over 100,000 West Indians in London, and not everyone welcomed them with open arms. The biggest problem of all was a huge shortage of housing to replace bombed buildings and unfit slums and cope with a booming urban population. The badly-conceived solution – huge estates of tower blocks – and the social problems they created, changed the face of London for ever. By the 1970s, with industry declining and unemployment rising, Swinging London seemed a very dim and distant memory.

Introduction by Dominic Sandbrook

In October 1965, the Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, officially opened London’s new Post Office Tower. A gleaming cylinder of metal and glass, the tower could hardly have been a more fitting symbol of the scientific optimism of a self-consciously ‘go-ahead’ decade. It was a monument not just to the white heat of the technological revolution, but to the sheer self-confidence of a society basking in unprecedented prosperity. From the new tower blocks springing up in cities across the country to the radios in teenagers’ bedrooms, from Beatles hits and Bond films to comprehensive schools and nuclear power stations, Sixties Britain seemed – superficially at least – to be a country reborn in the crucible of affluence.

In some ways, the cliches of the 1960s ring absolutely true. With the economy buoyant, unemployment almost non-existent and wages steadily rising, millions of families bought their first cars, washing machines, fridges and televisions. Millions of teenagers, too, were transfixed by the sound of Radio Caroline and the look of Mary Quant — although, then as now, Carnaby Street catered more for tourists and day-trippers than the tiny handful at the cutting edge of fashion. Television transformed the imaginative landscape of almost every household in the country, not merely through pictures of faraway places, but through satirical programmes such as That Was the Week That Was. Even the nation’s diet was changing, transformed not just by the arrival of foreign imports from chicken tikka masala to spaghetti bolognese, but by the relentless advance of the supermarket.

Beneath the glamorous veneer of swinging London, however, Britain under Harold Macmillan, Sir Alec Douglas-Home and Harold Wilson remained a remarkably conservative, even anxious society. Intellectuals worried that affluence and mass communications were undermining traditional working-class culture; in the Pilkington Report, published in 1962, it was hard to miss the disdain for commercial television. Meanwhile, despite the much-discussed stereotype of the ‘permissive society’, popular attitudes to moral and sexual issues remained strikingly slow to change. For all the excitement surrounding the landmark Lady Chatterley’s Lover trial in 1960, or the liberalisation of the divorce, abortion and homosexuality laws later in the decade, most people held similar attitudes to their parents; in this respect, the generation gap was a media invention.

And although students marched on the US embassy in protest at the Vietnam War, or staged sit-ins at universities such as the London School of Economics, it is easy to forget that only one in ten young people became students. Polls showed that like their elders, most young people still supported the death penalty and were uneasy about large-scale Commonwealth immigration; by the end of the decade, it is probably no exaggeration to say that the Conservative maverick Enoch Powell, who was kicked off his party’s front bench after his notorious ‘rivers of blood’ speech, was the most popular politician in the country. Even Mary Whitehouse, a ferocious critic of televised obscenity, especially on the BBC, commanded the instinctive support of tens, perhaps even hundreds of thousands of people.

By the end of the 1960s, the contradictions at the heart of the affluent society were becoming increasingly apparent. Despite Harold Wilson’s promises of endless growth thanks to his National Plan, the economy was running into serious trouble. The Aberfan catastrophe in 1966, the devaluation of the pound a year later and the Ronan Point disaster a year after that all hinted at the political and social traumas that would blight the following decade. Perhaps most ominously, Wilson’s last stab at modernisation, the trade union reforms outlined in the White Paper In Place of Strife, fell apart completely in 1969. A year later, the public punished the Labour government for its perceived under-achievement. A new and much unhappier era was at hand.

Dominic Sandbrook is the author of ‘White Heat: A History of Britain in the Swinging Sixties’.

A brief recollection-